Countless authors have used a city as their muse. As a young man, Ernest Hemingway wrote short stories about Paris, its wide boulevards and twisted sycamore trees, and the Seine snaking through the heart of the city. Joan Didion has devoted whole essays to capturing the ethos of cities from San Francisco to Las Vegas, “the most extreme and allegorical of American settlements, bizarre and beautiful in its venality.” Walter Benjamin celebrated gritty, industrial hubs like Marseille and wrote about flâneurs walking Paris streets.

Two recent books go a step further, taking a single street as their subject and using it as a microcosm for the vibrant chaos and layered past of an entire city. In The Only Street in Paris, Elaine Sciolino explores the rue des Martyrs, a quiet street that cuts through the French capital’s ninth arrondissement. Ada Calhoun goes even more micro, mapping out the history of just three blocks in New York’s Lower East Side in St. Marks Is Dead: The Many Lives of America's Hippest Street.

Not many streets could bear this kind of sustained attention, but these authors have plenty of material. Leon Trotsky, Andy Warhol, and Allen Ginsberg all lived or worked on St. Marks Place; Thomas Jefferson, Edgar Degas, and Edith Piaf all spent time on the rue des Martyrs in Paris. Both writers are vivid storytellers, and eventually, the streets seem to take on a life of their own, drawing vitality from each successive generation that lives there—the fruit vendors and wayward poets, homeless men and shopkeepers, artisans, activists, bohemians.

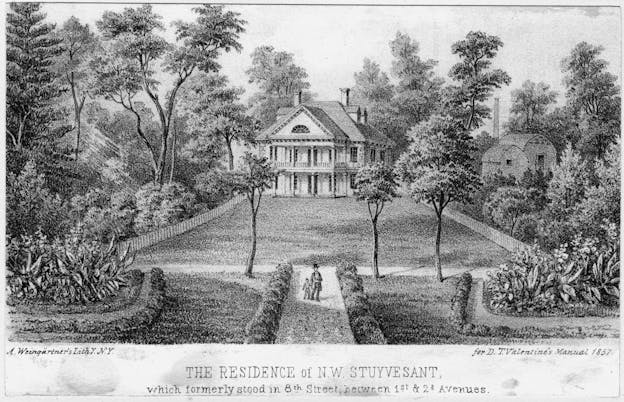

Calhoun, a journalist who grew up on the Lower East Side, starts her book in the 17th century, when the Dutch still controlled Manhattan and the Lower East Side was largely uninhabited farmland. Most people lived in New Amsterdam, a port city that drew pirates and prostitutes to the island’s southernmost tip, until Peter Stuyvesant, the director general of the colony—and a Calvinist— decided to move his family two miles north to escape the city’s lax morals. There, he built a farmhouse and a private chapel. In 1799, his descendants rebuilt the church, naming it St. Marks after the evangelist who wrote the Gospel of Mark.

As the city crept northwards along Manhattan, his farm gave way to a street plan, stately brownstones, and an influx of immigrants from Europe. By 1850, the area around St. Marks Place was a solidly middle class, immigrant neighborhood. It was still like that in 1917, when Leon Trotsky—newly arrived in in New York and living in a Bronx apartment—began working at a communist newspaper with headquarters on St. Marks. He left a mere three months later, heading back to Russia at the dawn of its revolution, but radical politics maintained a presence on the street; by 1919, it was known as "Hail Marx Place."

From then onwards, St. Marks had a colorful, less bourgeois, history. In the 1920s, dance halls and speakeasies cropped up, attracting bootleggers and gangsters to run them. (One mafia racket, called the Black Hand, distributed black lollypops to each child at a Lower East Side elementary school, sending a message to the parents that they had to fall in line.) And once prohibition ended, the street took on a more bohemian flavor. Young men were flooding home from World War II, and while many began their adult lives in Connecticut and New Jersey suburbs, others travelled to the East Village. "To them, the buildings represented only cheap, raw space for poetry readings and art galleries, plenty of room in which to be young," Calhoun writes.

By then, St. Marks had emerged as the nexus of a new literary scene. Carl Solomon and Allen Ginsberg lived there in the ‘50s. In 1952, the same year Jack Kerouac coined the term "Beat generation,” British poet W. H. Auden and his partner moved into a spacious apartment in the building where Trotsky had once worked. There, under a watercolor by William Blake that he hung across the mantle, Auden served martinis from jam jars to his endless stream of guests while cockroaches skittered across the floors.

Teenagers in thrall to On the Road followed Kerouac to New York in droves, and St. Marks became their playground. The Village Voice was their neighborhood guide. In its classifieds, you could find ways to "learn an instrument, meet people, stop smoking, go back to school, join a group, buy a farm, learn to belly dance, move your furniture cheaply... learn Tai Chi or King Fu, palmistry or urban conversational Spanish, or get in early on the grooviest pad in Kismet," Calhoun writes.

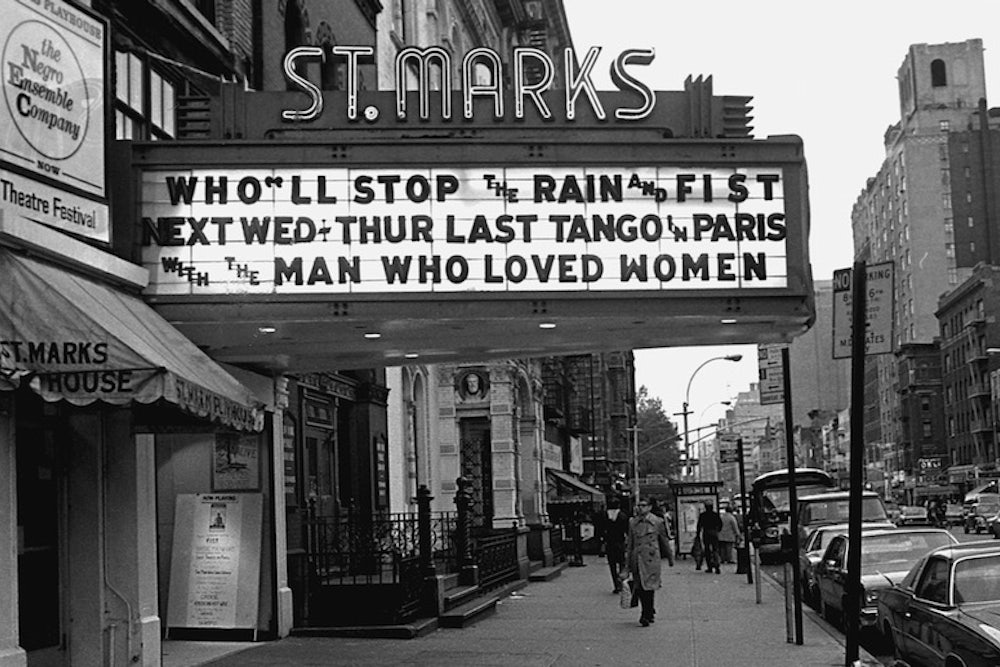

As time passed, the street continued to welcome outcasts and runaways. During the ‘60s, Beatles songs and the weed wafted down to the street from open windows, and drug dens became more common. Another decade passed, and punks took over. By the mid-‘70s, Calhoun writes, the "hippie haven had yielded to a decrepit mall of black-light posters, fringe vests, and incense." The last Ukrainian and German immigrant families were leaving, crime was up, and homeless people wandered the streets, looking for their next fix. This was the St. Marks Place of Calhoun’s New York City childhood.

"Every city has its famous ghosts," Sciolino writes. "Paris, with its long history and enduring magnetism for artists and writers, had more than most. A surprising number of them walk the rue des Martyrs." Sciolino, an American journalist who has spent the last 13 years in Paris as a writer and bureau chief for The New York Times, has written a less straightforwardly historical book than Calhoun. The Only Street in Paris is a blend of memoir and research, as Sciolino mixes her personal memories of expat life with the stories of artists and luminaries who walked rue des Martyrs before her. There is Thomas Jefferson, who romanced a married woman at the Jardin Ruggieri, the first French amusement park, while serving as American ambassador to France. Claude Monet, Paul Gauguin, and George Bizet were all baptized at Notre Dame De Lorette, a church at the bottom of the street. Edgar Degas, Auguste Renoir, and George Seurat spent days at the Cirque Fernando, a wooden circus. (It’s where Degas painted “Miss La La,” an acrobat hanging from a thin rope by her teeth.) Pablo Picasso spent 1909 in an artists’ colony nearby.

For most of its history, the street embraced a loose bohemianism, as the place where a Parisian avant garde crossed paths, meeting in bistros and cafes. "It was built," Sciolino writes, "to be populaire—solid, unpretentious, working class, poised between respectability and bohemia." And for the most part, it has succeeded in maintaining its original character. Even now, there are few tourists on the rue des Martyrs and no outposts of Zara, Starbucks, or Sephora. Instead, artisanal merchants occupy most storefronts. One family has run a butcher shop on the street since 1899. A nearby pharmacy appears in city records dating back to 1868.

There’s something distinctly French about the way rue des Martyrs has clung to its past, bent on preserving every cobblestone, building, and private garden. "The French are obsessed with history, partly out of a genuine affinity for the past, partly from a desire to cling to lost glory," Sciolino writes. They decry each passing change. When a local fishmonger closed his shop on the rue des Martyrs, they did exactly that. Local cooks were horrified that they would have to buy their fish at Picard—a French chain that specializes in frozen foods—just up the street. "It might as well be New York," one local shop owner told Sciolino.

Calhoun might not mind the comparison. In her book, she celebrates that flux, the way St. Marks has reinvented itself countless times over its history. What was once a solidly middle class immigrant neighborhood gave way to gritty bars and clubs during Prohibition. The street of the hippies gave way to that of the punks. It’s a very Americans approach to the past, one that would have been familiar to Alexis de Tocqueville. “Instability, instead of occurring to [the American] in the form of disasters, seems to give birth to nothing around him but wonders," Tocqueville wrote when he landed in New York in 1831.

Despite writing about the streets where she was raised, Calhoun has produced the less nostalgic book. This is where she gets the book’s irony-laden name: every time another movement swept over the street, erasing its predecessors, disgruntled residents declared that the St. Marks of their youth was “dead.” But the street always reemerged in vibrant new forms, and Calhoun insists the neighborhood—despite gentrification and sky-high rent—is no more dead now than it was 40 years ago.