In 1973, Kurt Vonnegut was asked by an interviewer why he started writing science fiction. “I was working for General Electric at the time,” he replied, “right after World War II, and I saw a milling machine for cutting the rotors on jet engines, gas turbines.” The machine was computer-operated, and it inspired Vonnegut to write a novel, Player Piano, about a future society in which industry has become completely automated, at enormous human cost. “There was no avoiding [writing science fiction],” he told his interviewer, “since the General Electric Company was science fiction.”

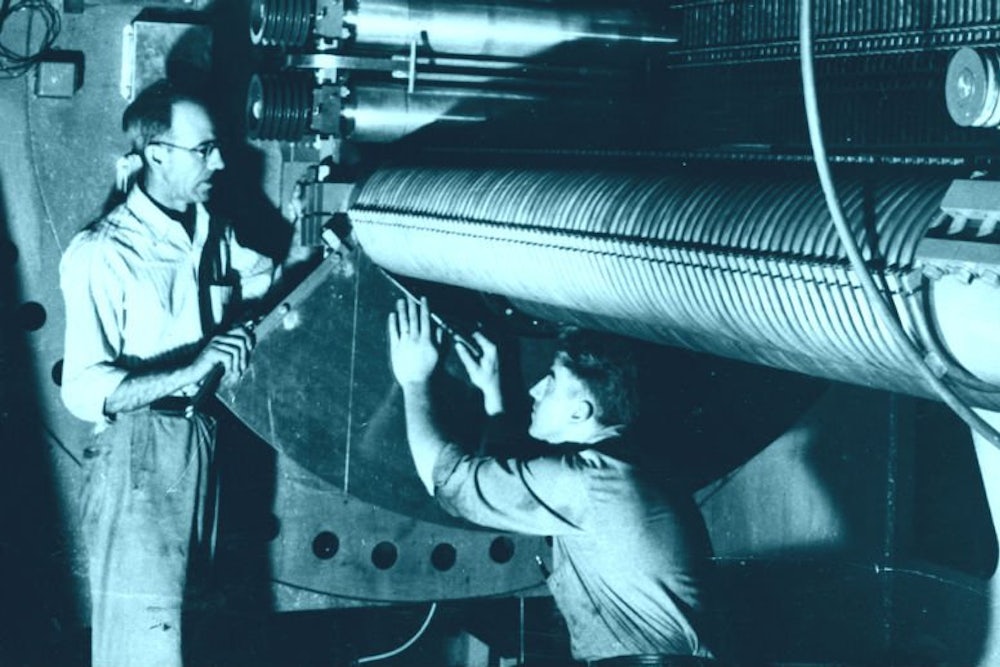

As Ginger Strand’s new book The Brothers Vonnegut: Science and Fiction in the House of Magic demonstrates conclusively, Vonnegut took much more than the milling machine from G.E. He worked in the company’s publicity department from 1947 to 1950, writing press releases and pitching stories on G.E. products and inventions to magazines and newspapers around the country. Vonnegut’s older brother, Bernard, was also employed there, as a scientist in the company’s research lab (nicknamed, by G.E.’s public relations experts, the “House of Magic”). From hanging around Bernard and the other denizens of the Schenectady Works, G.E.’s sprawling corporate campus in upstate New York, Vonnegut gleaned ideas for short, fantastic tales he could sell to popular magazines. Inventions and experiments by G.E. scientists inspired his early stories “Report on the Barnhouse Effect” (in which a telekinetic scientist refuses to use his powers for military purposes), “Thanasphere” (in which a boundary layer between the Earth’s atmosphere and outer space is filled with the voices of ghosts), and “epicac” (in which a superintelligent computer kills itself in a fit of existential angst). The substance “ice-nine”—which, in Vonnegut’s 1963 novel Cat’s Cradle, brings about apocalypse by freezing all the water on Earth—was based on an idea that Irving Langmuir, one of G.E.’s top research scientists, supposedly pitched to H.G. Wells on a guided tour of the Schenectady Works in the early 1930s. Wells did nothing with the concept; his loss was Vonnegut’s gain.

“The stories [Kurt] wanted to tell were G.E. stories,” Strand writes. He was inspired by “the worship of the company man; the mindless team spirit; the faith in progress, technology, and science; the enthusiasm for anything that reeked of the future.” Vonnegut’s G.E. stories were often bitterly satirical, presaging the increasingly bleak tone his fiction would take in later years. In an early draft of “Mnemonics,” suggested by the memory-building classes popular among ambitious G.E. employees, an office drone invents violent fantasies to help him remember everyday details: “To recall his boss’s extension, 717, Alfred imagines the boss with two seven-shaped hatchets in his body and a one-shaped dagger in his throat.” Stories like these suggest the balance of Vonnegut’s love-hate relationship with G.E. tilted toward hate: Stimulating as the environment was creatively, he was desperate to quit, and in December 1950, once he had sold enough stories to justify launching himself full time as a fiction writer, he did.

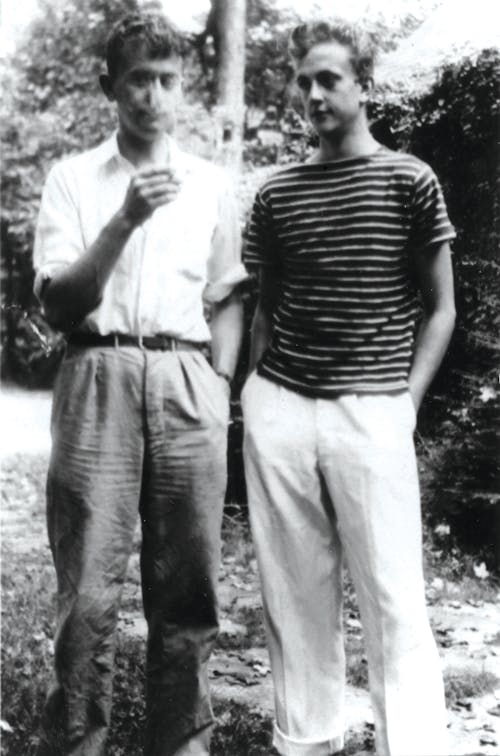

About half of The Brothers Vonnegut tells a familiar tale of Bildung: It’s the story of a writer becoming a writer, and it’s a compelling and uncommonly detailed one. Strand’s book focuses mostly on the period between 1945—when Vonnegut witnessed firsthand the bombing of Dresden, which would later inspire Slaughterhouse-Five—and 1952, when Bernard left G.E., apparently in a fit of conscience.

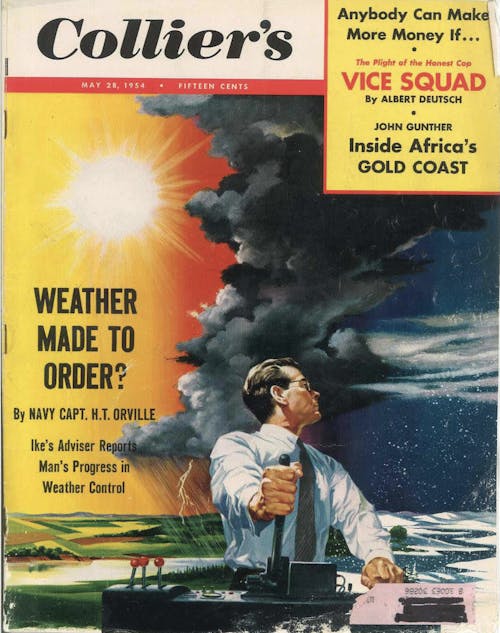

As an exercise in biographical literary criticism, Strand’s book is convincing and enjoyable, and fans and scholars of Vonnegut will be glad to have the specifics of this formative era filled in. But she also has larger ambitions to tell a grand, complex story about science, ethics, and politics. As its title suggests, The Brothers Vonnegut is a narrative with a double focus: It juxtaposes Kurt’s slow rise to literary fame with Bernard’s scientific exploits at the House of Magic. In the late ’40s and early ’50s, Bernard was working on something called “Project Cirrus,” a weather modification initiative that had its origins in wartime research on aircraft de-icing. Bernard, along with Langmuir and several other G.E. scientists, developed an experimental method called “cloud seeding,” which involved shooting pellets of dry ice (or later, silver iodide) into clouds in order to freeze the moisture within them, thus releasing latent heat and, ultimately, the scientists hoped, producing rain. When the initial trials of this technique appeared to be successful, there was considerable excitement from both the media—“Man Does Something About Weather,” the New York Post triumphantly announced—and the military, which immediately partnered with G.E. to develop cloud seeding as a potential weapon.

Many of the Bernard-centered sections of The Brothers Vonnegut are taken up with byzantine bureaucratic feuds between Project Cirrus, the Army, and the U.S. Weather Bureau, which was skeptical about cloud seeding and viewed it as a distraction from more important advances in computer-assisted statistical meteorology. Many famous midcentury scientists tromp through these pages, including the mathematician John von Neumann, who worked on computer prediction of weather patterns at the Institute for Advanced Study, and the physicist Edward Teller, who made crucial theoretical contributions to the development of both the atomic and the hydrogen bombs. Most prominent of all is the cyberneticist Norbert Wiener, an idol of Kurt’s, who, in 1948, publicly denounced the type of scientist who knowingly participated in the production of weapons technology as “a morally irresponsible stooge in a science-factory.” (One would guess that Bernard took this to heart.)

Strand does a good job explaining the science, for the most part (or, at least, good enough for a layman like me), but she is more than a little heavy-handed in treating the ethical questions that exercised Wiener and other scientists of his era. The Brothers Vonnegut is constructed as an innocence-lost narrative, in which both brothers begin by believing that “science was going to make the world a better place,” only to be steadily disillusioned by the actual consequences of scientific discoveries for human society in the second half of the twentieth century. She notes that both Kurt and Bernard supported the postwar scientists’ movement, which called for the creation of a world government to help curb and control the destructive potential of atomic weapons. This failed to come to pass, of course, and the two brothers found themselves dismayed by America’s entry into wars in Korea and, later, Vietnam, where cloud seeding was eventually deployed to try to extend the monsoon season in order to gain tactical advantage over the Viet Cong. (The secret program was codenamed “Operation Popeye,” which is a very Vonnegutian detail indeed.)

The problem with Strand’s book is not her claim that the Vonneguts were disappointed by the evolution of U.S. science after the war; a cursory reading of Vonnegut’s oeuvre would reveal as much. It’s that she barely ever lets them express these feelings in their own words, and the ones she provides for them are often hackneyed. For a book about a (wonderful) writer, The Brothers Vonnegut is strangely light on quotations; the endnotes reveal that Strand consulted both Vonneguts’ personal archives extensively, and she often refers to private letters, but in almost every case she renders these documents in paraphrase.

Moreover, Strand’s account of what went wrong with U.S. science in the latter half of the twentieth century is oddly framed. The culture of “Big Science”—a term first used by the physicist Alvin Weinberg in 1961, toward the end of the period chronicled in The Brothers Vonnegut—certainly has its dystopian aspects, not least in its connections to what President Eisenhower called “the military-industrial complex.” But Strand chooses to focus instead on how, in these years, being a scientist became less fun. The early House of Magic is portrayed as a delightful playground, which “encouraged its scientists’ fixations the way parents encourage a child’s passion for dinosaurs or ants.” But this spirit of childlike wonder is soon suffocated by the sinister agendas of business and government, not to mention the balkanization of science itself. Several times Strand refers to disciplinary specialization (which, we should note, was already well underway by the turn of the twentieth century) as a lamentable development. In the mid-’40s, she says, “the scientific disciplines were just beginning to divide into a series of silos, their boundaries patrolled by ever more focused specialists.” Bernard, in particular, is presented as one of the last of a dying breed of intrepid, generalist “Victorian scientists”: “Bernie was a tinkerer. For him, tinkering was what science was about. You played around with something until you understood it.” This innocent curiosity, Strand claims, was welcomed at the early G.E. Research Lab, before “the white-collar world of the scientists, allied with the government and the military, [began] edging away from the blue-collar world of the Works and into its rarefied technocratic sphere.”

Langmuir, too—the man who gave Wells, and later Vonnegut, the idea for ice-nine—is presented as a brilliant, admirable oddball. In the early ’50s, Langmuir went head-to-head with the Weather Bureau, seeking to prove (via statistics) that cloud-seeding trials had affected rainfall in New Mexico in the summer of 1949, while the Weather Bureau sought to prove (via different statistics) that they hadn’t. “For all his brilliance, Langmuir had failed to see the irremediable flaw in his method pinpointed by the bureau statisticians,” Strand writes. “Langmuir’s calculations of probabilities for rainfall in seeded areas assumed that rain in one area could be considered independently of rain in the next—that in looking for patterns, he could treat rainfall levels as if they were random numbers. But rain in one place is probabilistically related to rain in a place nearby; a touch in one place eddies and flows, setting up a touch in the next.” The Weather Bureau’s analysis took this interconnectedness into account, while Langmuir’s didn’t.

From this, Strand concludes ruefully that Langmuir “did not see that his whole way of doing science—his generalist, do-it-yourself, paper-clip-and-string mode of Victorian science—had become a liability.” But we’re not talking about Big Science versus Victorian science here, really: We’re talking about good statistics versus bad statistics. Langmuir was simply wrong, and we don’t need to reach for broad sociohistorical explanations to understand why he lost out to the Weather Bureau on this one. Strand also equivocates about the effectiveness of cloud seeding itself, which she admits, is still viewed skeptically by many meteorologists: “The general consensus today is that in certain conditions it works in a limited way,” she hedges, though “the huge modifications Irving [Langmuir] promised never came to pass.” If cloud seeding was not, as now seems likely, an important scientific discovery, is it really the best vehicle for a narrative about the decline and fall of Victorian science? Maybe it was simply a dead end?

All of this would matter little if Strand were able to show us Kurt and Bernard Vonnegut as complex, vulnerable human beings, the way Vonnegut shows us characters like Billy Pilgrim, Dwayne Hoover, or Professor Arthur Barnhouse. We are repeatedly told the relationship between the Vonnegut brothers was close, but we get virtually no evidence of their actual rapport. Early on, Strand sketches the Vonnegut family dynamic—“[Kurt’s] brother was brilliant, and his sister was artistic and beautiful. He couldn’t compete on brains or talent or glamour. So he nurtured his penchant for humor.”—but what follows is short on descriptions of actual interactions between the siblings, and sister Alice, whom Vonnegut idolized and to whom he devoted an entire novel (Slapstick), barely appears at all. A traumatic occurrence that would seem to be crucial to the emotional lives of the Vonnegut brothers during this period—the drug overdose, and possible suicide, of their mother Edith in 1944—is mentioned in passing but never really investigated. All of these seem like missed opportunities; and while it’s possible the Vonnegut estate prevented Strand from making use of materials that could have shed light on some of these mysteries, she could still have found a way to at least gesture at some of her narrative’s darker corners.

The Brothers Vonnegut is a fascinating but, ultimately, frustrating book. You can sense on every page Strand’s excitement at having such rich primary sources to work with, and she does right by them in enough instances that you wish she had been able to pull the whole together into something more satisfying. But there are just too many moments when she shies away from complexity in favor of pathos. “Science—real science—was always a complex story,” Strand writes, ventriloquizing Bernard’s opinion on the cloud-seeding controversy. “It was rare for things to be black-and-white, for evidence to be irrefutable and results to be obvious to all.” Yet the story Strand tells is, when it comes down to it, pretty black-and-white: Bernard’s “research had been intended to bring the benefits of water down from the sky, to create a kind of anti-Dresden, an anti-Hiroshima. An explosive showering of life, not death, from the clouds.” When it becomes clear weather modification will be used to wage war as well, he quits G.E., because “good guys stayed true to their love of science, their pursuit of knowledge for the good of humanity. Bad guys were venal. They made choices based on money.”

Good guys, bad guys: It’s easy to endorse this binary view of history, and to congratulate our idols for ending up on the right side of it. But it’s not this sort of certainty that brings us back to books like Player Piano or Cat’s Cradle or Slaughterhouse-Five or, for that matter, Mother Night, a Vonnegut novel from 1962 which reflects many of Strand’s themes—guilt, complicity, responsibility, trauma—in a way that suggests what The Brothers Vonnegut might have been. Mother Night isn’t science fiction; it was Vonnegut’s first attempt at a different genre, the spy novel. The plot—inspired by the trial of Adolf Eichmann, which was then underway in Jerusalem—concerns an American named Howard W. Campbell, Jr. who, like Eichmann, is put on trial in Israel for Nazi war crimes. Campbell had delivered a series of incendiary anti-Semitic broadcasts from Berlin during the war. But, he claims, he was actually a double agent, delivering secret coded messages to the Allies, the content of which he never knew.

The question that animates Mother Night is whether Campbell is telling the truth about his double-agent status, but also, more troublingly, whether that matters. Was Campbell a good guy or a bad guy? The answer depends on the facts but also on how you weigh actions against intentions, power against will. “You think I was a Nazi?” Campbell asks Frank Wirtanen, the colonel who (supposedly) recruited him for his secret espionage mission years ago. “Certainly you were,” Wirtanen replies. “How else could a responsible historian classify you?”

But it isn’t that easy, of course; moral classification is always a problem, even for responsible historians. Kurt Vonnegut never forgot that.