Exactly 150 years ago this Tuesday, Confederate Captain Henry Wirz climbed the steps of the gallows in the courtyard of the Old Capitol Prison in Washington, D.C., where the U.S. Supreme Court building now stands. A hood and noose were placed over his head, and the trapdoor flew open. The fall did not snap his neck but left him to slowly strangle. The crowd of some 250 witnesses cheered and applauded. The life of America’s most notorious war criminal was over, but the battle over his legacy was just beginning.

Wirz, the commandant of the Confederacy’s prisoner of war camp in Andersonville, Georgia, was perhaps the second-most hated person in America, after John Wilkes Booth. “There are deeds, crimes that may be forgiven; but this is not among them,” Walt Whitman wrote of Wirz’s crimes. “It steeps its perpetrators in blackest, escapeless, endless damnation.” And yet, not far from the graves of Wirz’s victims stands a monument celebrating the man responsible for their horrific deaths.

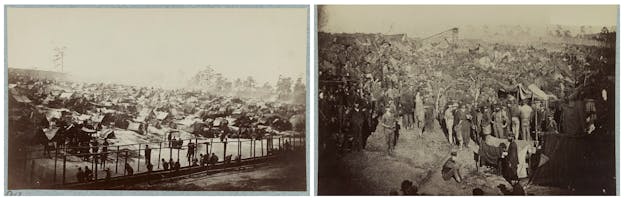

During Wirz’s fourteen months in charge of Andersonville, 13,000 Union prisoners of war died from disease, starvation, exposure, medical neglect and murder. At its peak in August of 1864, more than 33,000 POWs were held in 26 acres of open ground. The only source of water was a small creek which ran dark with sewage. Rations, if they came at all, were barely enough to sustain life. Prisoners were never issued clothing or provided shelter, and lay under makeshift tents or in holes dug in the ground wearing the same ragged pieces of their uniforms for the duration. Everything in the camp, a prisoner later testified, was covered in lice and overrun with vermin. Witnesses also testified that Wirz personally murdered and tortured prisoners, and ordered guards to do the same.

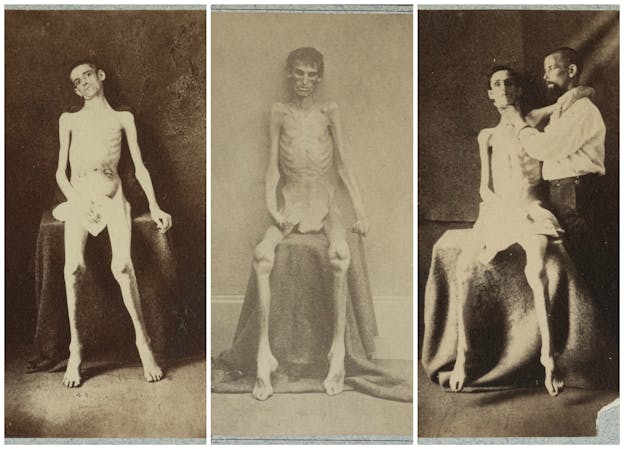

No Civil War prisoner of war camps, North or South, were country clubs. At the converted state prison in Alton, Illinois, more than 1,500 Rebels died in custody from disease. But no prison approached the death rate or deliberate cruelty of Andersonville. After the surrender at Appomattox, stories of survivors began flooding the Northern newspapers. The photographs of the survivors, starved into living skeletons, were like nothing the world had seen before and would not see again until the liberation of Nazi death camps at the end of World War II. Wirz was arrested and taken to Washington.

Wirz, a native of Zurich, Switzerland, presented a defense in his heavy German accent that he was only following orders. He claimed he could not feed the prisoners adequately because the South had no food to spare. Wirz blamed the overcrowding on the North’s refusal to continue the practice of exchanging prisoners. (He did, in fact, parole five prisoners to go to Washington to ask the Union to take some of the prisoners off his hands. After the Union refused them, the five men, as they had promised, returned to Andersonville.)

The trial lasted two and a half months with almost 150 witnesses. General Lew Wallace, who would later write the book Ben Hur, presided over the tribunal. Wirz was acquitted on one charge of murder but found guilty on the other charges of murder, abuse, and violations of the laws of war. The military barely had time to print the tickets for the clamoring spectators before Wirz was marched to the gallows on on November 10, 1865. Two others were executed for lesser war crimes and hundreds more were tried for non-capital offenses, but Wirz’s trial and execution closed the case in the public’s mind.

Wirz’s body was barely cold in its unmarked grave when Southern apologists began a campaign to make Wirz a martyr or a scapegoat. A key witness against Wirz was soon revealed to be living with a false identity, enough to fuel the conspiracy theorists ignoring the substance of his testimony. Southern writers claimed Wirz’s trial was unfair, citing his absence from Andersonville on one of the days specified in the charges. The Lost Cause true believers even blamed the North for forcing the South to mistreat prisoners. The cult-like devotion to clearing Wirz even prompted some Southerners to seek a presidential pardon.

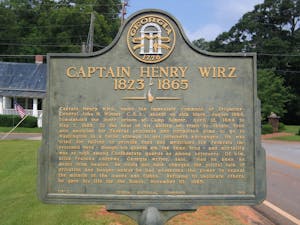

After the war, veterans returned to the site of the Andersonville camp. They were able to identify all but about 400 prisoners buried there, and establish a national cemetery. Sixteen Northern states erected monuments to their dead. In 1909, the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) decided to erect their own monument to Wirz. Some UDC members lobbied for placing the tribute in Richmond, or the Georgia towns of Macon or Americus. But the majority decided to build the obelisk in Andersonville, barely a mile from the site of the prison.

The tall stone monument contains four panels. One of them reads, “Discharging his duty with such humanity as the harsh circumstances of the times, and the policy of the foe permitted Capt. Wirz became at last the victim of a misdirected popular clamor.” He was, the panel reads, “condemned to ignominious death on charges of excessive cruelty to Federal prisoners.” Another panel states, “To rescue his name from the stigma attached to it by embittered prejudice this shaft is erected by the Georgia division, United Daughters of the Confederacy.” At the time Union veteran organizations protested, but the monument still stands today and the conflicts have moved to the Internet.

The Confederate flag has come under fire lately, following the mass murder in June at a black church in Charleston, South Carolina. The flag was taken down from its pole on the state’s capitol grounds, and last month students at the University of Mississippi successfully protested for the state flag, which incorporates the Stars and Bars, to be removed from campus. How can it be that the rebel flag comes under attack while a monument to a convicted war criminal responsible for 13,000 deaths, erected almost on top of their graves, is left unprotested? The Confederate flag is a part of history, even though it is part of an ugly history; the monument to Wirz is a distortion of history. The true test of the commitment to stop the glorification of the Lost Cause will not come over flagpoles or license plates but on monuments like the one to Henry Wirz.