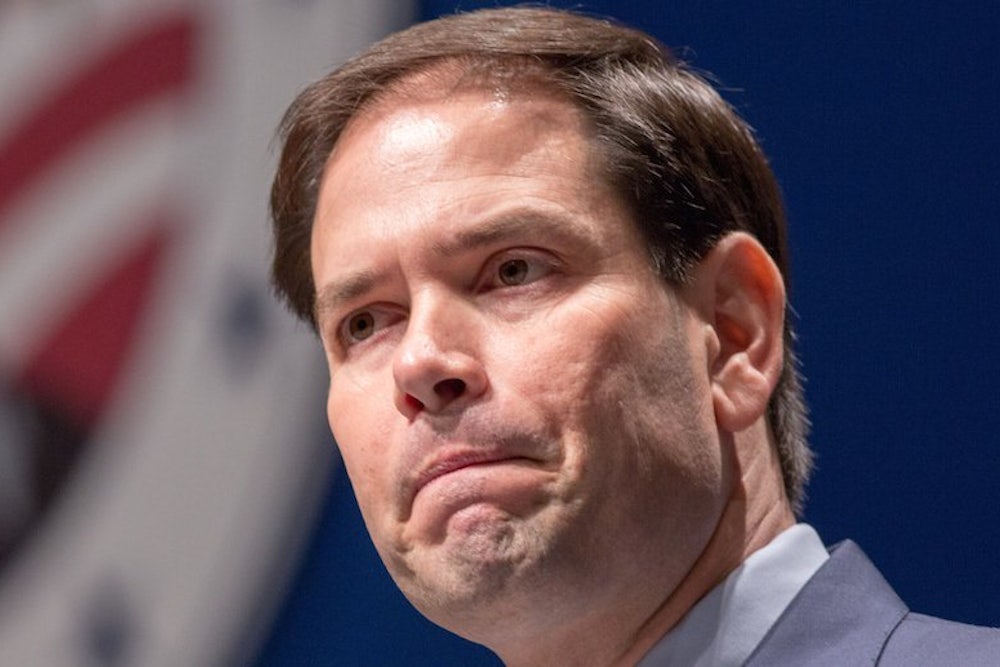

As we approach the fourth Republican debate, it’s striking that some of the most astute observers of American politics now see Marco Rubio as the frontrunner for the nomination—albeit, in the words of New York Times columnist Ross Douthat, “a very strange sort of frontrunner.”

Douthat’s proviso is worth attending to, because by any normal measure, Rubio isn’t a frontrunner at all. His frontrunner status has the quality of a quark, or one of those other odd sub-atomic particles that only exist because scientists imagine they do. According to the Huffington Post’s aggregation of the polls, the top four Republican candidates are Donald Trump at 27.5 percent, Ben Carson at 22, Rubio at 10.6, and Ted Cruz at 8.9. Real Clear Politics tells much the same story. To put these numbers starkly, if Rubio doubled his support, he would still be in third place behind Trump and Carson. And Cruz, who is rarely described as being in the top of the pack, falls into the same range of popular support as Rubio.

Rubio won't likely move the needle with stellar debate performances—he's had three of them so far, if you ask most pundits, and it's had only a negligible effect on his popular support. In fact, his peak poll numbers came earlier this year, before the debates began. Rubio also lags behind in other relevant metrics, like party endorsements. According to a recent overview by Aaron Bycoffe on the website FiveThirtyEight, Rubio ranks fourth in endorsements, after Jeb Bush, Chris Christie, and Mike Huckabee. (It’s true, though, that there has been a recent upsurge in endorsements for Rubio—and that Republican Party leaders have been very slow to endorse anyone thus far.)

So maybe it's money that's convincing everyone Rubio will be the last Republican standing? Not quite. Rubio recently had a fundraising score when he snagged the support of billionaire Paul Singer, who is not only a sugar daddy in his own right but influential in getting other plutocrats to open up the money bags. Still, Singer’s backing followed a period of lackadaisical fund-raising. As the Washington Post reported last month, “Rubio’s $5.7 million haul during the third quarter of the year was less than half of the totals put up by Bush, Cruz, and Carson, even as he focused intensely on raising money.”

To date, then, Rubio has proven a mediocre candidate by any reasonable measure. So how do we explain the rush to hail him as the likely winner? As Douthat observes, Rubio earns the nod “by process of elimination.” Trump and Carson are viewed as too extreme and inexperienced not to crash and burn. Cruz is the darling of the Tea Party base, but hated by Republican officials and his colleagues in Congress. Fiorina lacks political experience, money, and organization. Bush is thrashing around like a turkey afraid it’s about to become Thanksgiving dinner. John Kasich, Christie, Huckabee, and Rand Paul are slowing sinking, though their demises have been less dramatic than Bush's. And you have to remind yourself that Bobby Jindal, George Pataki, and Lindsay Graham are still in the race. So, simply by crossing out the names of every other candidates for one reason or another, all you have left is Rubio.

But at some point, voters will have to agree. The process-of-elimination argument works better as a deductive scenario than as an account of how voting actually works. The idea that Rubio will triumph in the end is partly founded on the last two GOP presidential races, both of which had the narrative arc of a soap opera. In both 2008 and 2012, the Republican Party acted like a wealthy heiress who threw herself into wild flings with wild scoundrels (Mike Huckabee, Herman Cain, Newt Gingrich) before finally settling down with a respectable mate (John McCain, Mitt Romney). Douthat explicitly draws the analogy with Romney, suggesting that the GOP will settle for Rubio just as it entered into a largely loveless marriage with the former Massachusetts governor. The problem with this analogy is that both McCain and Romney were more substantial figures than Rubio: They could flash not just impressive resumes (McCain as war hero, Romney as governor and business leader), but also a genuine popularity with large constituencies in the GOP. Romney never sank below 20 percent in the polls in 2012, a figure Rubio has yet to even remotely touch.

Rubio faces a two-front battle going into the fourth debate. He has to substantially boost his following with the base while continuing to reassure the establishment that he's the best candidate for the general election. This is a difficult balancing act; it's easy to tip too far one way or the other. His opposition to abortion in all circumstances already hurts him as a general-election candidate, even if it helps hims with evangelicals in the GOP; Bush allies are telling The New York Times, in fact, that they're poised to run a series of attack ads claiming Rubio's stance on abortion makes him unelectable. In effect, they're signalling to the donor class that Rubio is a bad bet who will sink the party in the general election. For Rubio, it's another sign that he will have to display remarkable flexibility in trying to sell himself simultaneously to the base and the big money.

Will Rubio be the Republican nominee, then? With all those caveats, there’s a good chance that he will. The other candidates are so tainted or limited that Rubio might be the last man standing, the one figure that a divided party can rally behind. Younger than the others, he may prove nimble enough to thread the ideological needle of pleasing a hard-right base and rich backers who are fixated on winning the general. But that doesn't change the fact that, as a nominal frontrunner and quark candidate, Rubio is hardly the galvanizing leader the party might want as it tries to retake the White House.