I am not trendy. In fact, I actively disdain something as soon as I sense it’s a trend, not because I want to be cooler than everyone else but because many of my tastes solidified years ago. I still dress like I did in first grade and the most-played music on my phone is from 2007. But that couldn’t stop me from falling prey to one of the latest trends: succulents.

I noticed other people’s obsession with succulents before I became obsessed myself. For months I had seen them in shop windows and garnishing coffee tables on design blogs. First one friend, then another, shared photos of their new apartment, cropped to include the succulents on the windowsill. I did not entirely understand the appeal. Why would you opt for a strange cabbagey plant when you could have flowers?

But somewhere along the way, my stance on succulents started changing. I found myself thinking that maybe if I had a succulent, my apartment—my life in general—would look like the chic spaces on Apartment Therapy and A Beautiful Mess. My succulents would say, I have taste. I am cool and slightly quirky. My external space is a reflection of my interior poise. I have my act together enough to take care of an actual living plant.

First, I acquired a light green echeveria that grew a single yellow flower. Then I got another, darker echeveria. And a hen-and-chicks. And a big spiky aloe. And a fairy castle cactus. There was no turning back.

I went to thrift stores and kept my eyes peeled for planters or, even better, random household objects that I might be able to turn into planters. Could that lovely blue Mason jar be home to a beautiful assortment of succulents? It didn’t have a drainage hole at the bottom—could I drill one? I didn’t have a drill—might I be able to use a hammer and a nail file to carve a hole? Did I even have a plant to put in a new planter? A perfect excuse to buy one! Was I likely to stab myself with the nail file while I attempted this? I probably wouldn’t bleed out, right?

More recently I learned that you can easily breed your own succulents by removing the leaves and waiting for new rosettes to form. That’s it! Not only do succulents make you feel instantly competent because they refuse to die from neglect, they miraculously transform you into a skilled botanist.

Now my kitchen window is home to a burgeoning crop of baby plants. Every morning I lean in close to examine the microscopic progress of the new roots, thinking about how I will pot them once they are fully-grown, waiting greedily for the day when I will have even more succulents.

But it’s not just my own succu-mania: Succulents are having a moment. (For the record, any plant that stores water in fleshy leaves, stems, or roots is a succulent. All cacti, for example, are succulents, but not all succulents are cacti.) Google searches for “succulents” grew by over 5000 percent between 2010 and today. On Etsy you can order 100 succulents at a time. The “succulove” Instagram account has 65,000 followers. Scroll through the over 1,500 posts and you will find succulents of all colors and textures in wreaths, vintage tins, cow skulls, and more. Brides magazine has published extensive lists of how to incorporate succulents into your wedding: not just in your bouquet, but as your table runner, a floral crown, or on your cake. Shops like Urban Outfitters sell hanging planters, Scandi-chic ceramic pots, and terrariums with burnished brass edges so you can display your collection in style.

Why is everyone so obsessed with succulents? Do they secrete a highly addictive narcotic oil on their leaves? Are we currently under the influence of a manipulative alien mind ray, or a mass hysteria?

In fact, the trendy plant is itself a trend, repeated throughout history. Plants have periodically been a conduit for society’s most powerful consumptive urges, and those urges have often been even more powerful than they are in the current succu-mania.

For example, in the seventeenth century, the Dutch fell so rapturously in love with tulip bulbs the flowers were treated as stock futures. Special vases were designed to best display the flowers, and people invested their life’s savings in a tulip market where a single bulb was worth the same as a large house. In 1637 the bubble burst and some investors were left bankrupt or in debt. Tulipomania now enjoys a healthy afterlife as a dire warning about speculation in economics textbooks. (So far, I don’t think anyone other than nursery owners is investing her life savings in succulents.)

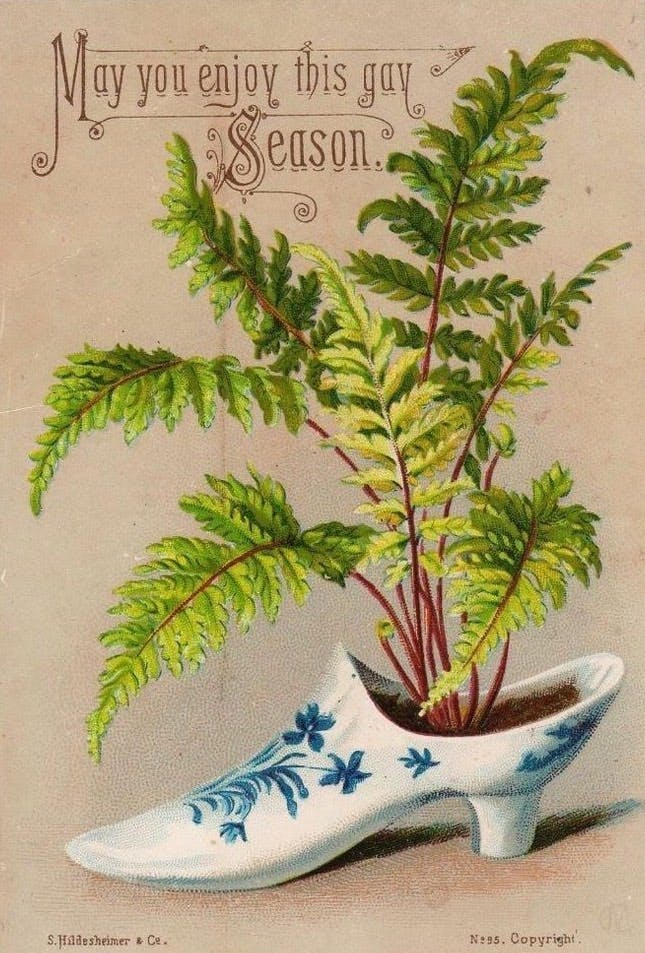

Then, there was Pteridomania: “fern madness,” which gripped Victorian England with the strength of a highly infectious disease. “Pteridomania affected men, women, and children of all classes throughout the British Isles, the Empire, and America,” writes Sarah Whittingham in Fern Fever: The Story of Pteridomania. Landowners feared hoards of fern robbers, and by 1906 fern collectors had done such damage to the countryside that the counties of Devon and Somerset enacted laws prohibiting the uprooting of wild ferns except “in small quantities for private or scientific use.” Fern designs crept into wallpaper and textiles, china patterns, and paper goods. You could send a fern-adorned Christmas card to your fern-loving friends, or impress with a green silk fern-covered dress, accented with a fern-shaped jeweled broach.

Succulents have not quite reached the level that ferns once attained, though you can buy watercolor prints of echeverias and laser-cut plastic necklaces in the shape of prickly pears (I know because I have one). But it is not a coincidence that both our contemporary capitalist system and our tendency towards fads are inherited from the Victorians. Trends—even ones involving plants—are driven by the bandwagon effect and intensified by the market.

“When people are free to do as they please, they usually imitate each other,” wrote the philosopher Eric Hoffer in 1954. When you see many people with succulents (or ferns, or tulips) you want succulents, too. One psychological explanation for this is the human tendency towards observational learning, which can lead to an “information cascade.” Instead of actively analyzing the pros and cons of a decision (to buy a succulent, or not to buy?) you look at what others have done, and how it has worked out for them (that person sure looks content with their succulent!). This can lead to localized conformity, where everyone in a school or a suburb or a country starts to resemble one another in terms of behavior.

The internet has complicated local conformity because it allows people to sort themselves by sub-culture rather than geographic location; makeup trends, for example, hopscotch back and forth between South Korea and America via YouTube stars. Looking at a thousand photos of succulents online will eventually convince you that you want a succulent, too, especially once they start showing up around you in real life.

Like many other trends, succu-mania began in California. For a long time California’s high-end landscape designers favored English-style cottage gardens, a green status symbol amidst a desert. Although succulents had been popular as easy houseplants, “the general perception of succulents among the gardening public was that they were a poor man’s plant, that they were common, they weren’t what a sophisticated gardener wanted,” said garden writer Debra Lee Baldwin.

A decade ago the mood began to shift. Baldwin noticed landscape designers using succulents to mimic the stark lines of contemporary homes. This wasn’t the first time in history designers were so inspired: Early twentieth-century architects felt that cacti and succulents were the only plants to really complement their sensibilities—a break from the more romantic plants favored by the Victorians. “The Modernist seized on the Cactus because of its strange shape,” says a 1931 issue of House & Garden magazine. “In Germany, where the Modernist movement in architecture and decoration appear to thrive, the indoor winter garden of Cactus and succulents is commonplace.”

Inspired by what she saw, Baldwin published a book in 2007 called Designing with Succulents. To Baldwin and her publisher’s surprise, Designing with Succulents spent 19 weeks as the bestselling gardening book on Amazon. From there, powered by the internet, succu-mania spread across the country.

The simple explanation for the explosion of succulent popularity is the same feedback-loop of supply and demand that fuels any trend, but there might be deeper, scientific reasons at work as well. In the 1970s, researchers in Pennsylvania found that hospital patients with a view of trees had faster recovery times and needed significantly less pain medication than those facing a wall. Since then, other studies have shown that proximity to indoor plants increases productivity and fosters creativity. In an age when more and more people are moving into cities, houseplants help soothe urban ennui.

Succulents may also be appealing to another biological instinct: Some grow in a spiral pattern that follows the Fibonacci sequence, which is mathematically related to the Golden Ratio. Fibonacci spirals are closely related to fractals, never-ending patterns formed by the repetition of a single shape. (“If you divide a fractal pattern into parts you get a nearly identical reduced-size copy of the whole,” explains Wired.) A Swedish study published this year concluded that viewing naturally-formed fractals provoked alpha activity in the brain—neural oscillations that indicate a “wakefully relaxed state and internalized attention.” It’s interesting to note that ferns, that source of Victorian mania, grow following a fractal pattern even more closely than succulents.

But the fundamental appeal of succulents may have nothing to do with science—and more to do with our inherent laziness. Succulents are the closest plant to plastic, and you really have to try for it to die. For a millennial obsessed with authenticity in this pre-apocalyptic age of the Kardashians and social media, there’s nothing better. I barely have to remember to water my succulents; they survive in spite of me. I get to feel like I am somehow connected to the earth with minimal effort. Blossoms fade after a few weeks, kitchen herbs freeze if they’re left next to a frosty window, but succulents live on.

Maybe I’ve been brainwashed by homogenous consumerism, the internet, or hypnotizing fractals, but I love my succulents. I don’t mind that I may be mocked like the fern-hunters before me. I just like coming home, in the dead of an East Coast winter, to little pots of green and a slice of the desert sun.