There’s a very funny photograph taken by Brassaï of Pablo Picasso posing in his Paris studio. Picasso had acquired a giant oil painting of a nude woman from an antique shop, and he strikes an affected pose before it, his brush poised and his little finger extended, as though he’s preparing to make the finishing touch on a masterwork. The actor Jean Marais is stretched out on the floor beside him, pretending to serve as the model despite being fully dressed. The target of the joke is clear: Picasso was ridiculing the pretensions and conventions of the professional painter. “I am not a professional artist,” Brassaï recounts him repeating, “as if he were claiming innocence of a slander.”

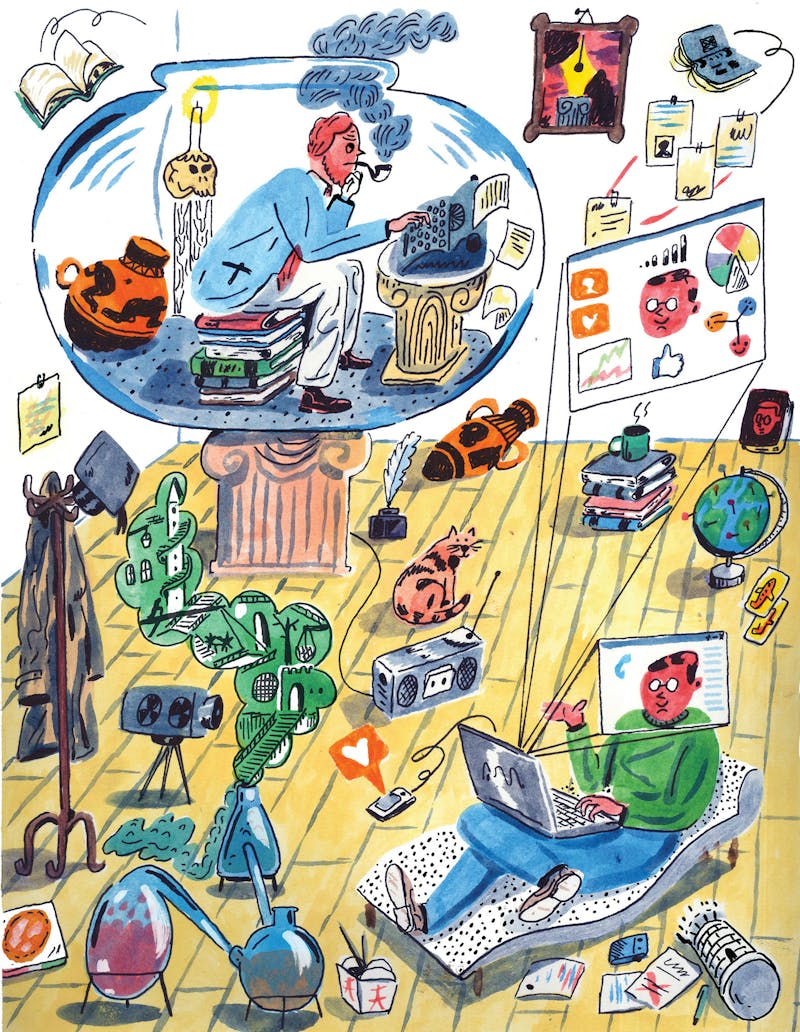

The same question vexes literature, too: Is writing an art or a career, or can it be both? The Unprofessionals, the title of a new anthology of American writing from The Paris Review, defines itself against the emergence of a hyper-professionalized breed of fiction writer. In his preface to the anthology, editor Lorin Stein laments that a familiarity with social media has made young authors almost unthinkingly proficient as publicists for themselves and their friends. Even in M.F.A. programs, he argues, the tricks of self-promotion have been woven into the craft of writing, resulting in “less close reading, less real criticism, lower standards, and less regard for artistic, as opposed to commercial, success. … Young writers, in other words, were encouraged to think of themselves as professionals: to write long and network hard.”

Of course, the professionalization of writing has a long, and mostly respected, history. Writers as varied as Samuel Johnson, Charles Dickens, and Mary McCarthy would have been outraged to be called anything other than professionals, and when you push past Mark Twain’s most renowned books, you find a lot of writing that did little more than spin off from his celebrity. But today’s forms of authorial self-promotion often seem to depend upon a mastery of social media outreach—a talent only recently connected to the crafting of prose. Consider the extraliterary responsibilities expected of authors who have had their novels accepted for publication: Develop an active presence on Facebook and Twitter (and, for the truly motivated, on Tumblr, Instagram, and Pinterest); create an accompanying web site, video trailer, and soundtrack; go on a book tour, naturally, but also participate in a variety of reading series in anticipation of and well after the publication date; take part in panels and signings at book expos; give interviews to blogs and podcasts and write personal essays about your background, your development as a writer, and your process of creation; not only review other books but join the great merry-go-round of blurbing; perhaps you’ll even personally attend book clubs.

The Unprofessionals, as Stein presents it, exhibits a lofty indifference to such spectacle. He characterizes The Paris Review as a kind of elite artist’s colony whose sole mandate is the refinement of craft. The twelve stories and novel excerpts in the anthology (which also features poetry and essays) are by writers whose ages range from their late twenties to their early forties; five are winners of the Plimpton Prize for Fiction, the magazine’s annual award for new voices. Stein notes that The Paris Review has a distinguished history of discovering important writers, from Philip Roth to David Foster Wallace, and its intention here is to anoint the finest talents from the noisy and crowded coming generation. Stein brings his own impressive track record as an editor at Farrar, Straus & Giroux, where he worked with Jonathan Franzen, Jeffrey Eugenides, and Richard Price, and helped bring foreign writers such as Roberto Bolaño to the attention of American audiences.

The anthology further boosts its credentials as a showcase for serious literature by claiming the imprimatur of realist fiction, the mode of writing traditionally given pride of place in literary awards and prestige venues like The New Yorker. Nearly all of its stories are tonally and stylistically alike, tracing a lineage from John Updike, Joyce Carol Oates, Richard Yates, and Lorrie Moore. These are, most commonly, vignettes of sin and suffering amid milieus of privilege—what the bard of suburban discord John Cheever called “the worm in the apple.” The married couple in April Ayers Lawson’s “Virgin” looks like a pair of blissful newlyweds, but the story lays bare the truths of sexual trauma and infidelity. In Peter Orner’s “Foley’s Pond,” an infant—perhaps egged on by her older brother—drowns in a neighborhood pond, which is then filled in and converted to a pretty, manicured park.

The writing in The Unprofessionals excels in finely shaded psychological subtlety. “The thing about a dark truth is it is indistinguishable from doubt,” Amie Barrodale writes in “William Wei,” about the ennui of hookup culture. The dominant mood is one of unsettled ambivalence, which often inflates into a pervasive tristesse. The opening story, Ottessa Moshfegh’s “A Dark and Winding Road,” immediately snags on this sense of underlying confusion, as a man considers his rural family cabin:

It was deadly quiet up there. You could hear your own heart beating if you listened. I loved it, or at least I thought I ought to love it—I’ve never been very clear on that distinction.

Moshfegh in particular seems to embody the qualities championed by the anthology. Her impressive novella McGlue (about an alcoholic sailor) and her debut novel Eileen (about a murder in a dreary small town) are purposefully spiky and unbeautiful, reveling in their atmosphere of gloom and misanthropy. Moshfegh has done little to make her books inviting or relatable. Eileen is almost unique in being published without an author photo. “When I read a novel, I want my sense of self to disappear,” she has said.

As though to rebut some of the assertions of The Unprofessionals, there is New American Stories, an anthology edited by the writer Ben Marcus and published earlier this year. Marcus is best known for his surreal and disorienting short fiction in the collections The Age of Wire and String and Leaving the Sea, and as a vocal spokesperson for experimental literature. His 2005 essay in Harper’s, “Why Experimental Fiction Threatens to Destroy Publishing, Jonathan Franzen, and Life as We Know It,” was a passionate (if overheated) broadside against the timidity and uniformity of American publishing. Whereas Stein is an editor charged with elevating the few from the many, Marcus has emerged as an emissary for a wide range of writers on the margins of the mainstream.

Marcus is, therefore, less of a behind-the-scenes tastemaker than an ambassador for the literary community at large and, in particular, writers who don’t have a ready place in the contemporary canon. At more than 750 pages (nearly three times the length of The Unprofessionals) his anthology is a gathering of styles and influences, mixing realism with historical fiction, fables, fantasies, dystopias, and a few pieces too miscellaneous to categorize. Veterans like Deborah Eisenberg and Robert Coover are mixed among a lengthy roster of newer, little-known names. Marcus explains the catholicity of his selections in his own introduction, writing that he “aims to present the range of what short-story writers have been capable of in the previous ten years or so.” If The Unprofessionals is like a beautifully unified concept album, New American Stories is, to use Marcus’s analogy, a mixtape.

Two superb stories give some sense of its range. “Another Manhattan,” by Donald Antrim, is the sort of work that would fit seamlessly in The Unprofessionals. Antrim is the author of three blackly comic novels (The Hundred Brothers imagines the biggest and nastiest family reunion in world history), but his short story, about two couples having affairs with each other, is situated squarely in the Upper East Side of John Cheever. This is the world of sophistication, dissipation, and well-dressed despair, and the writing assumes the kind of elegant omniscience achieved by only the most supremely confident of storytellers—like this vivid snapshot of a man exiting a flower shop: “Had you been walking downtown on Broadway that February night at a little past eight, you might have seen a man hurrying toward you with a great concrescence of blooms.”

Then there’s “The Diggings,” by Claire Vaye Watkins, whose recent debut novel Gold Fame Citrus centered on a thrillingly imagined postapocalyptic American Southwest buried under a massive, shifting sand dune. “The Diggings” is a gold-rush story that draws from and exuberantly parodies nineteenth-century historical records. Watkins freely partakes in the sense of lawlessness and adventure that animate those accounts. One gruesome scene describes the carnival spectacle staged for the prospectors of a grizzly bear fighting a bull. (“Where the bull’s nose had been was now only a dark cavity from which dangled stringy bloodpulp. ‘My,’ I breathed.”) But the pastiche has a sensibility that would not have been present at the time—an ironic awareness of the racism, greed, and cruelty of these mythologized figures. Watkins gleefully ransacks the literary archives for historical arcana, but she puts her own modern stamp on the story.

Two anthologies, two visions of American fiction: one exclusive, one eclectic; one that seals its ears to the clamor of the industry, one that takes inspiration from the chorus of voices being published. The second vision has the stronger sense of political purpose. Many new writers want to be read and discussed by a large audience, to be noticed by prize committees, to take an active part in the cultural conversation—all activities of the so-called professional—not because, contrary to Stein’s opinion, they’re out for money, but because this kind of recognition is central to the politics of their writing. For those who start within the establishment, professional writing is likely to correspond to drudgery, and they’ll seek to escape it. For those on the outside looking in, it’s a mark of legitimacy, and something to aspire to.

The stories in Marcus’s anthology reflect the interest many new writers have in rearranging social hierarchies and redefining terms of normalcy. Rivka Galchen’s “The Lost Order,” for instance, is a comic retelling of James Thurber’s “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty,” with a housewife in the role of the daydreaming everyman. (Galchen’s wildly inventive 2014 collection American Innovations, which is as likely to truck in the supernatural as in realism, is built on appropriating classic stories for contemporary women.) Here the heroine spends the bulk of her day talking on the phone with people who have dialed the wrong number and trying to find her lost wedding ring. The underlying point is that the ordinary, even hapless, doings of women merit the same close attention as those of men.

This equalizing trend is important in fiction today. The critic Parul Sehgal has written cogently about the “radical transparency” of recent novels and nonfiction that make women’s lives their subject. In her essay in Bookforum last year, she uses as an example Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation, a 2014 novel composed of jagged sentence fragments that reflect the constant interruptions motherhood imposes on Offill’s writing (not included in Marcus’s anthology, though it would fit in). But Sehgal makes the crucial point: The fragments are “less a performance of alienation than a passionate effort at reconciliation.” Radicalism, she suggests, is not found in authors turning their backs on the mainstream, but in forcing the mainstream to widen its scope. These are writers traditionally left outside of the conversation and eager to be recognized as professionals.

There’s a well-trod narrative path in many of the stories in Marcus’s anthology: stories that follow outsiders—minorities, immigrants, victims of abuse, of illness, of loss—who are struggling toward social acceptance while trying to redeem a tainted sense of self. “A Man Like Him,” by Chinese émigré Yiyun Li, concerns a teacher in a Chinese village whose life has been destroyed by a false accusation of pedophilia. It’s written with the sensitivity and muted desperation of one of William Trevor’s rural Ireland sketches, ending with the teacher’s Trevor-like (or Chekhovian) “gentle willingness” to accept his persecution. In “Shhhh,” by NoViolet Bulawayo, the young Zimbabwean narrator’s father is gruesomely succumbing to AIDS. At one point her friends come to stare at the dying man: “We just peer in the tired light at the long bundle of bones, at the shrunken head, at the wavy hair, most of it fallen off, at the face that is all points and edge from bones jutting out.” The story brings a distant nightmare from the shadows of awareness into a painfully vivid focus. It humanizes the unimaginable.

The Unprofessionals orients itself towards the literary establishment in a very different way. The Paris Review, the tweedy great-uncle of American literary journals and bastion for traditional realism, is very much a cultural insider. Since its founding in 1953 it has been symbolized by its charming man-for-all-seasons editor George Plimpton, who gave it its lasting reputation for erudition and style, and who ran the magazine until his death in 2003. Although the anthology takes on some of the same themes as those in Marcus’s, these stories tend to be drawn outward, from the established center to the strangeness of the margins. They sow discomfort by undermining middle-class assumptions. Whereas New American Stories is likely to begin with the foreign and unfamiliar and make them sympathetic, The Unprofessionals lulls readers away from the conventional and everyday with its limpid prose and toward the edge of some psychological abyss.

A running theme in The Unprofessionals is the sliding status of male protagonists, fiction’s archetypal heroes, a trend the critic Elaine Blair identified in her 2012 essay “Great American Losers,” which looked at male-crisis fiction by Gary Shteyngart, Sam Lipsyte, and others. Zadie Smith’s “Miss Adele Amidst the Corsets,” which is enlivened by the author’s keen sense of class and ethnic conflict, follows an aging New York drag queen’s journey to buy a new corset. Lawson’s “Virgin” and Benjamin Nugent’s “God” center on different forms of emasculation; in the latter, set in a frat house, the only guy who succeeds in bedding an intimidating coed is the closeted narrator, who’s really thinking about his frat brothers. The conventional, hollowed-out husband of Moshfegh’s “The Dark and Winding Road” plummets into depths of sexual debasement (“It wasn’t painful, nor was it terrifying, but it was disgusting—just as I’d always hoped it would be”).

Some of the book’s most impressively controlled passages come in Garth Greenwell’s “Gospodar.” An almost unbearably intimate account of an American man’s humiliating sexual encounter with a Bulgarian in Sofia, the story brings a kind of culmination to the anthology’s demolition of traditional manhood:

I found myself at last at the end of my strange litany saying again and again I want to be nothing, I want to be nothing. Good, the man said, good, speaking with the same tenderness and smiling a little as he cupped my face in his palm and bent forward, bringing his own face to mine, as if to kiss me, I thought, which surprised me, though I would have welcomed it. Good, he said a third time, his hand letting go of my cheek and taking hold again of my hair, tightening and forcing my neck further back, and then suddenly and with great force he spat into my face.

Less dramatic but as insidiously disturbing is Angela Flournoy’s “Lelah,” excerpted from her first novel, The Turner House. Flournoy, a recent graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and a National Book Award finalist, is on one level writing a persuasive and preternaturally cool depiction of a Detroit resident succumbing to a gambling addiction (“A stillness like sleep, but better than sleep because it didn’t bring dreams”). But its underlying provocation lies in the fact that, though it expertly navigates the terrain of addiction and bankruptcy claimed by writers like Raymond Carver and Richard Ford, its solitary main character is female.

Very little of the writing in these books feels new, in the sense of experimental. There’s a powerful emphasis on empathy in today’s literature, and while these stories push against received values and are often emotionally difficult, they tend to be written accessibly, with a goal of identification and connection.

New influences in their work tend to come from writers of genre fiction, traditionally ignored by literature’s gatekeepers. Marcus picks out some of the most interesting of these experimenters. He includes a long, inscrutable fable by Jesse Ball, who has said that his fiction is partly informed by his practice of lucid dreaming, the ability to be aware of and exert control over your dreams. There is a bluntly effective climate-change dystopia by Wells Tower, who is always looking to play with pop-culture conventions. The title story from his excellent collection Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned is about wised-up Vikings, and it fits broadly with Colson Whitehead’s reenvisioned zombie novel Zone One and Donna Tartt’s profusely elaborate fairy tale The Goldfinch.

This kind of infusion of cult sensibilities into the corpus of realist fiction has resulted in some of the most exciting and popular novels of the twenty-first century, from the comic-book homages of Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay to the postapocalyptic novels of Cormac McCarthy and Chang-Rae Lee. But the most influential writer in Marcus’s collection is George Saunders, whose groundbreaking stories in CivilWarLand in Bad Decline (1996) and Pastoralia (2000) demonstrated that you could forge fiction from the supernatural, the absurd, or even the purely comic without sacrificing its moral and political intent, and without ruining your chances of being published in The New Yorker. Saunders has a newish story included here—“Home,” about a returning soldier—but it’s his earlier work, which imagines an alternate America losing its soul to dystopian corporations, that has inspired so many young writers. In Saunders’s writing anything can happen: Characters can live in caves, they can be mutants, they can come back from the dead. They project an exhilarating creative freedom.

Saunders’s sorts of parallel worlds—partly satirical, partly allegorical, partly just plain-old weird—crop up repeatedly in Marcus’s selections. Some come from writers who have emerged from M.F.A. programs, and others from the world of science fiction. Lucy Corin’s “Madmen” presents a rite of passage in which teenagers adopt and care for their own personal lunatic. Charles Yu’s “Standard Loneliness Package” imagines a company that lets people outsource any pain they’re experiencing to low-wage workers at a call center. Maureen McHugh’s “Special Economics” pits a pair of plucky, hip-hop-dancing young women against a dystopian corporate juggernaut and manages the trick of being simultaneously hopeful and bleak. And Saïd Sayrafiezadeh’s “Paranoia,” taken from his scandalously overlooked 2013 collection Brief Encounters With the Enemy, evokes the deep, dissociative strangeness and latent cruelty of the Americans at home during wartime (we never learn exactly when the story is set) even more effectively than Saunders’s own story.

These stories are fertile and inventive, but they work by co-opting forms of popular entertainment, not by subverting them. Most of today’s dystopian fiction has the characteristics of a heartwarming family drama. Wells Towers’s story, “Raw Water,” for instance, imagines a future in which the Southwest is covered under a “do-it-yourself ocean” called the Anasazi Sea, but it largely concerns a married couple trying to adjust to circumstances, and in that sense it is not far different from the preoccupations of Cheever and Updike. The desire for inclusion and accessibility now goes hand in hand with most experimentation.

What is only rarely found is fiction that starts on the outside and, by virtue of formal innovation and the manipulation of language, stays outside. These are books that deconstruct the very act of reading. Marcus includes a few such stories. Rachel B. Glaser’s “Pee on Water” is a curious parable of human evolution whose choppy syntax and obscure juxtapositions frustrate attempts at interpretation. (“Chairs are rare. They sit patiently in rooms. Mutton fat is boiled to make soap. Rocks are fired out of bamboo poles.”) As clarity is kept in abeyance, the focus shifts to other components of the text—the sound and meaning of words, the sensations of intellectual displacement. But the truth is that American fiction has very little dedicated avant-garde. The few who doggedly (and brilliantly) pursue it—Percival Everett, Lance Olsen, Stephen Dixon, among others who don’t find a place in these anthologies—are our real unprofessionals, since very few are reading them.

Yet there is at least one writer who has managed to bridge these (admittedly, somewhat artificial) divisions between unprofessional writing for the cognoscenti and professional writing for the public. Ben Lerner is currently something of a critical darling, and he’s just received a MacArthur “Genius” Grant. Yet he is something of an unlikely candidate for literary lionhood, as his first books were works of postmodern poetry. He came to public attention only after the appearance of his slyly autobiographical debut novel, Leaving the Atocha Station, a coming-of-age story about a poet living in Spain, the success of which ironically jump-started Lerner’s career as a professional writer of prose.

The Unprofessionals excerpts a long section from his follow-up work of fiction, 10:04, one of the most trenchant (and comical) explorations into the dilemmas of producing literature in the United States in recent years. Broadly, the book follows a year in the life of the autobiographical narrator from the moment he is offered a six-figure book contract to the point when the book itself is complete. Lerner digs into questions of commodification and authenticity, of politics and artistic responsibility. But his novel is not simply a bildungsroman; it tells the story of the formation of itself, tracing its own evolution from a clever vanity project to a kind of testament of fellowship.

In a virtuoso passage, Lerner’s narrator (who is different yet indistinguishable from himself) looks across the East River on the illuminated Manhattan skyline and is moved, like Walt Whitman apostrophizing the body electric, by the feeling of community it inspires in him. It has the refined, poetic prose exalted by Stein, but it yearns for the kind of communion and understanding valued by Marcus:

It was a thrill that only built space produced in me, never the natural world, and only when there was an incommensurability of scale—the human dimension of the windows tiny from such distance combining but not dissolving into the larger architecture of the skyline that was the expression, the material signature, of a collective person who didn’t yet exist, a still-uninhabited second-person plural to whom all the arts, even in their most intimate registers, were nevertheless addressed.

It’s good to remember, in contrasting these two anthologies, that beyond their oppositions they have one big thing in common: Their writers are young and their stories bespeak promise rather than consummation. It will likely be through novels, not stories, that they will make their reputations. What matters is not which direction they go, but whether or not they’ll have the time and persistence to create truly individual work along the way.

Proof that it can be done is found in the few stories in Marcus’s anthology that are written by seasoned hands and that display a mastery of style or a mastery of perspective (which are much the same thing). Christine Schutt’s portrait of a newlywed couple, “A Happy Rural Seat of Various View: Lucinda’s Garden,” carries windswept echoes of Virginia Woolf and Elizabeth Bowen, but Schutt has so thoroughly absorbed her influences that the prose announces itself as hers in a matter of words: “They were happy. They were at sea; they were at the mess, corkskinned roughs in rummy spirits, dumb, loud, happy. And they really didn’t have so much to say to each other.”

Then there’s Denis Johnson’s “The Largesse of the Sea Maiden,” the kind of story that is created from impressions and details stored up over a lifetime. (Johnson says that the piece developed over a period of 38 years, and that he wrote it in about seven.) Little happens in this story of aging adman Bill Whitman, but Johnson’s dispassionate gaze somehow takes the measure of the man’s soul, and the quiet scenes are gold-flecked with, as he puts it, “certain odd moments when the Mystery winks at you.” Johnson could be in Stein’s anthology as well as Marcus’s (he’s appeared in The Paris Review repeatedly over the years). But that just means that he’s achieved the aim of all writers: He’s transcended categorization. It no longer makes any difference how you label him—professional or unprofessional—since he’s written fiction good enough to outlive him.