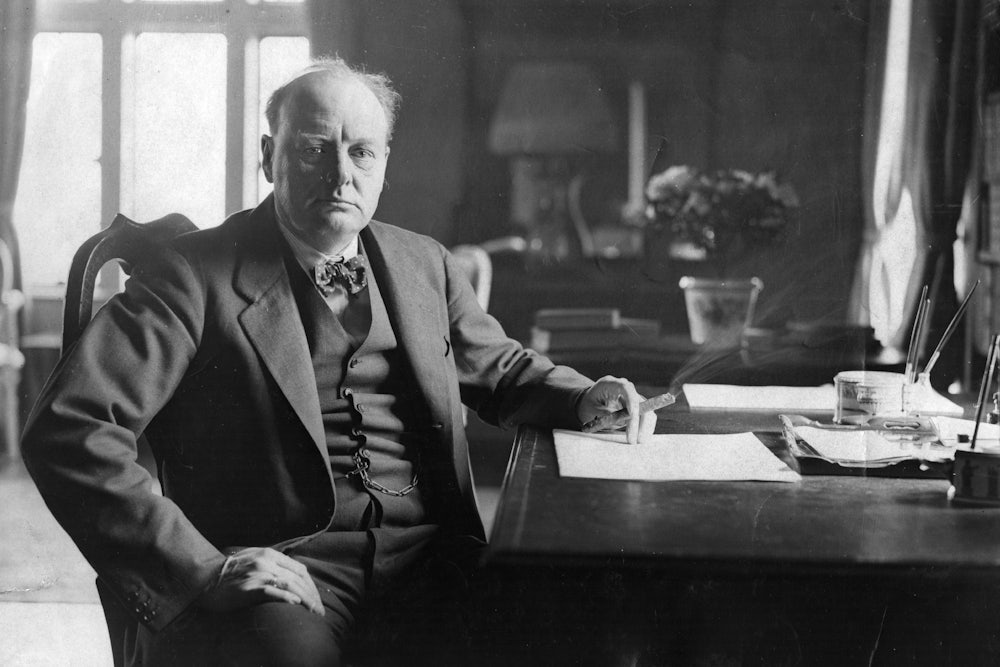

“An accepted leader,” wrote Winston Churchill in Their Finest Hour, “has only to be sure of what is best to do.”

“If he is no good,” Churchill added, “he must be poleaxed. And, taking him at his word, the British poleaxed Churchill in 1945. But since, in a time of flux, Churchill above all free men is sure of what is best, he remains the accepted leader of the Western World.

Churchill can rise to an occasion by remaining silent. At Boston, an immense stage was set for him to point the way ahead in a grand gesture. Churchill merely thumbed his nose at the Great Khan.

His silence did not reflect his indecision. He proceeds one step at a time. Since as he spoke the next, all-important step—the North Atlantic Pact—was before the Senate, Churchill, preeminently the politician, chose not to peer into the future. In addition, Churchill, astride the Atlantic, sees no reason why his American hand should know what his European hand is doing. Too widespread a discussion of over-all strategy would deny to him and to Britain the powerful role of intermediary. So he makes one speech in America and another altogether on the European continent. Pieced together, they begin to form a pattern.

Churchill, as he confessed at The Hague in May, 1948, never accepted the concept of the United Nations. He feared the consequences of “a system where there was nothing between the supreme headquarters and the commanders of the different divisions and battalions.” He wanted a world organization made up of representatives of regional associates.

The associations, Churchill felt, should consist of “three splendid groupings”: the USSR, the Western Hemisphere, and Europe and the British Commonwealth. In this manner, Asia would be left to the subjugation of empire; Russia would be excluded from most of the world; America would be excluded from Europe, and Europe would be merged with the Commonwealth, to maintain the primacy of British power.

Between these associations and the tacit partnership of Britain and America, Churchill conceived some undefined relationship. His initial reaction to the East-West conflict which he alone in the West had foreseen and prepared for, was to urge at Fulton in March, 1946, the open recognition of the British-American alliance. His immediate proposal was economic cooperation and “the continuance of the intimate relationship between our military advisers.” “Eventually,” he added, “there may come the principle of common citizenship, but that we may be content to leave to destiny.”

The logic of the Fulton speech was confirmed by

Soviet actions. Its program was implemented by the

British and American governments. Yet the speech itself

was howled down in both countries. So the relationship

between the concept of Europa and the concept

of Atlantis, was established. Churchill concluded that

while the intimate relationship of the British and

American governments would prosper, the fraternal

association of the two peoples would take years to

ripen. The peoples of Britain and Europe, therefore,

should be joined in federation before the peoples of

America and the British Commonwealth would unite in

a larger union.

Churchill, who paid little attention in wartime to union among the governments in exile, became the president of the Council for European Unity. Just as he ignored Europe at Fulton, so before the Council he spoke only of the support of America and mentioned also “that third great and equal partner,” the USSR.

At Fulton, Churchill called for “a good understanding on all points with Russia under the general authority of the United Nations.” As long as this seemed possible, the reorganization of the UN and the creation of permanent organizations of the West were not part of his concept of leadership. In fact Churchill made it clear that he saw the Council for European Unity chiefly as a propaganda device by welcoming to its sessions delegates-in-exile from Eastern European states.

Late in 1948, however, Churchill blasted “false hopes of friendly settlement” with Russia. He ruled out all hope for settlement by fixing as its terms the liberation of all satellites, and the retirement of the Russians behind their own borders.

By then, East and West had met in Paris to join the ERP, and had gone their own ways. The UN had become to Churchill “a brawling cockpit.” Minority rights in Eastern Europe were crushed. The governments of America and Western Europe had swung to full support of European federation. Organization became an immediate problem. Bevin proposed a federation on functional lines. The French favored a legislative approach. Churchill insisted on a legal entity. At The Hague in February, 1949, he proposed that a European Supreme Court be added to the contemplated Council and Parliament. And at Brussels he called for the reorganization of the UN.

No wonder clarification is necessary today! Quite apart from the UN, and its specialized agencies, and the myriads of common councils that link the Western nations, four major groups of the West are rising. Sixteen nations and the Bizone are joined in the OEEC. Five of these nations are joined to advance economic, political, cultural and military union in the Brussels Pact. Three of them are joined in penelux, a full economic union which when it takes effect in June, 1950, will become a separate trading entity: the third largest in the world.

Ten OEEC nations, together with Canada and the US, have joined our military and other purposes in the North Atlantic Pact.

Between these associations, what are the relationships

to be? Should America participate in OEEC planning,

for example, giveh that ECA will soon end? If the OEEC is permanent, what is its relationship to the

European Council and Parliament? How and when is

the Brussels union to be extended to the OEEC nations?

Will the administration of the military lend-lease program,

and the planning of joint defense, be placed

under the European federation or the continuing councils

of the North Atlantic Pact? Is the European federation

or the Atlantic union to be the regional association

of the West, and what other regional associations are

to be formed? What is the relationship to be between

the West and the remainder of the free world?

Decisions on these issues cannot be long delayed. They affect the economies and the political direction of all participating countries. Britain, for example, has recovered economically by highly nationalistic controls. What is to become of them? At the same time Britain has transferred her political sovereignty over the determination of peace and war, first to the Imperial Conference of the British Commonwealth, then to the Security Council and the General Assembly of the United Nations, now to the Brussels union, and once more to the North Atlantic alliance. Soon Britain may relinquish these powers all over again in a complete merger of sovereignty in a European federation. What, then, happens to her other commitments, particularly when they all conflict? If bigamy is a crime among nations, the British are convicted many times over. And, if we take our commitments seriously, so are we.

Governments may be able to shuffle many decks of cards. Peoples cannot be easily manipulated. Allegiance requires loyalty, but to what are the British people to be loyal? Are they subjects of a British King, or Europeans, or members of a Commonwealth, or followers of an embryonic Atlantic union, or citizens of the UN whose supreme allegiance is to the Charter?

Each Western nation shares the British dilemma. There is a need for vision, and here Churchill fails.

One major problem is the integration of the European economies. They require drastic reorganization. But Churchill concedes his ignorance of economics an his resistance to change. Always a Tory, he cannot accept the one peaceful solution to the cold war, displacement of Communism by economic reform.

A second major problem is Germany. Conflict concerning the role of Germany has been the greatest single barrier to the unity between the French, the British and the Americans. Rightly the Americans insist on German recovery; rightly the French fear Germany; rightly the British trust only the German Socialists. Churchill understands that European federation is the only way to control a divided Germany. But he extends his hand to the German nationalists, as he does to Franco, and so destroys the political basis of federation.

A third major problem is the relationship of Europe and Asia. Only within the larger unity of the entire free world can true European unity be achieved. But Churchill sees in Asia only a vast area for colonial exploitation. He congratulates the Dutch for their war on Indonesia. He dimly equates Communism and Asia as a new yellow peril and denies utterly to Asia its equal role in world organization.

The West cannot be united as means of perpetuating privilege, or as a way of saving colonialism, or as an instrument of war. And since these are Churchill’s ultimate purposes, we cannot afford Churchill as the accepted leader of the West.

As the Soviet government breaks its last ties with the West, we are led down Churchill’s road. We continually look backwards to what was, and what might have been, and so we stumble, rather than march forward. We cannot accept as final the breakup of the World. So we leave the UN’s future largely for the Russians to decide. We improvise, as we must, and as the clock ticks on we wait for a miracle to happen when the Great Khan dies.