America has been lucky with its demagogues, who until recently have self-destructed or run into ruin before they could do a maximum amount of damage. As Donald Trump continues to poison public discourse with his open racism, most recently in his call to bar all Muslims from entering the United States, it’s worth reflecting on the fate of earlier rabble-rousers like Father Charles Coughlin and Joseph McCarthy.

Both of them in their heyday dominated headlines the way Trump does now, with divisive, mudslinging politics, filled with lurid lies and outrageous conspiracy theories. Both Coughlin and McCarthy flourished for longer than they should have. But both had their careers ended by the national media and effective institutional opposition from the organizations that nurtured them—the Catholic Church in the case of Coughlin and the Republican Party in the case of McCarthy. The unavoidable question is: Are there contemporary institutions that can rein in Trump?

Father Coughlin, a Canadian-born and -educated Catholic priest, settled in Detroit in 1923, and got his start as a political broadcaster in a benign way in 1926 with a religiously focused weekly radio address. In the early days, Coughlin’s show was largely apolitical, aside from its critique of the Ku Klux Klan’s anti-Catholicism. With the onset of the Depression, Coughlin increasingly preached a message based on Catholic social thought that emphasized the dignity of labor and the need to ameliorate poverty.

During these Depressions years, Coughlin became enormously popular, with an audience that at times reached 30 million. In keeping with the church’s social teachings, Coughlin was both anti-capitalist and anti-socialist, arguing for a Christian-inspired middle path of economic cooperation. For a time, he was an ardent supporter of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, but turned against the Democratic president by the mid-1930s, because he thought FDR was too beholden to financial interests.

Coughlin’s turn against Roosevelt was coupled with an increasingly strident anti-Semitism, as he blamed the Depression on Jewish bankers and republished The Protocols of the Elders of Zion in his journal Social Justice. Coughlin’s conspiratorialism and anti-Semitism were met with a strong pushback from within the Catholic Church and from political liberals. Economic boycotts pushed Coughlin out of key radio markets like New York. Prominent clergymen, like Monsignor John Ryan of Catholic University in Washington, took to the airwaves to argue that Coughlin’s economic nostrums, which included some oddball monetary schemes, were not in keeping with church teachings.

Although the Vatican wanted Coughlin off the air, he was for a time protected by Bishop Michael Gallagher of Detroit. Gallagher’s successor, Bishop Edward Mooney, took a stronger stance against Coughlin. In 1942, he ordered the priest to end his broadcast career and return to pastoral work. In sum, the hierarchical nature of the church proved strong enough to put the lid on Coughlin, even though it had let him run on for far too long.

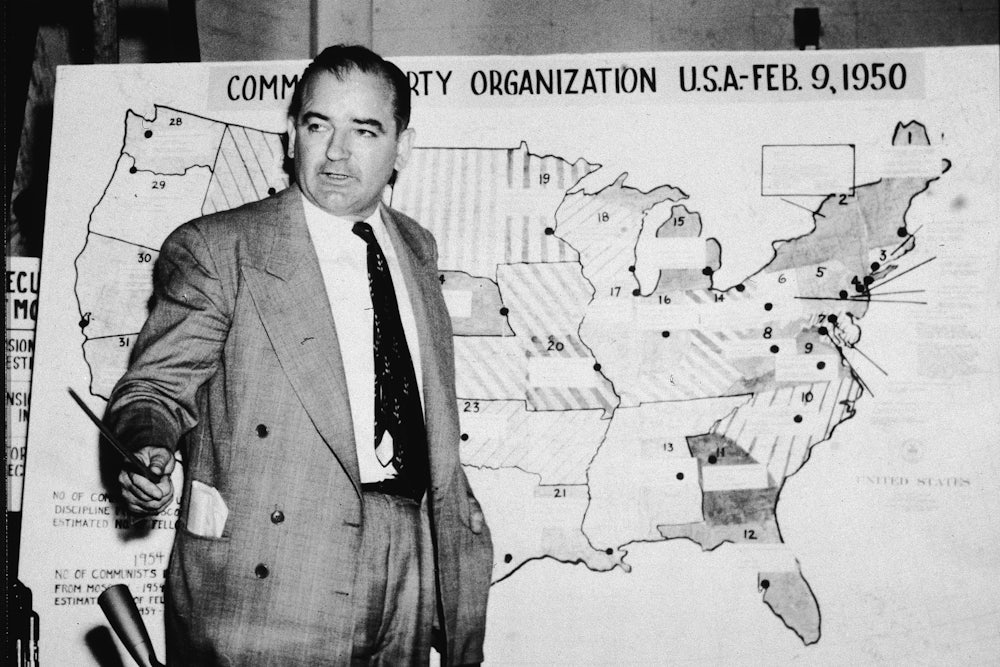

The anti-communist demagogue Joseph McCarthy followed a similar trajectory. For a few years in the early 1950s, he was the darling of the Republican Party and the right-wing media because of the political usefulness of his accusations that New Deal liberalism was infected with communism. Politicians like Dwight Eisenhower were happy to campaign with McCarthy while media outlets like The Chicago Tribune and Time magazine amplified his voice.

But in 1954, McCarthy made the mistake of attacking the army, a popular institution that was able to stand up to the Wisconsin senator. It was an army lawyer, Joseph Welch, who unleashed a devastating attack on McCarthy during a televised hearing, famously asking, “Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency?” Later in 1954, the Senate voted to censure McCarthy, a motion that won the support of half the Republicans in the Senate. After the censure, many of McCarthy’s friends in the media deserted him.

Writing in The Atlantic in June of this year, Peter Beinart drew some parallels between Trump and McCarthy, seeing Trump as having a potentially similar downfall. “Although it’s too early to declare Trump’s political career over, the last few days resemble McCarthy’s descent in 1953 and 1954,” Beinart wrote, following Trump’s attack on John McCain’s war record. Beinart, in fact, was premature: Trump came out of that firestorm stronger than ever. And the larger question remains whether Trump’s fate will ever resemble McCarthy’s.

As flawed as it was in 1954, the Republican Party was still strong enough to stand up to McCarthy. Once the Senate censured him, he lost standing. In 2015, it’s not clear that the Republican Party as an institution has the muscle to take on Trump. He doesn’t need the party for money and he holds no elective office. So there is almost nothing the party can do to rein him in. Meanwhile, the mainstream media’s reputation has never been worse, and it is particularly suspect among Republican voters.

The downfalls of demagogues like Coughlin and McCarthy show the importance of strong institutions in keeping in check rabble-rousers and hate-mongers. But where are such institutions now?