I once did something I’ll probably never do again: I read a new novel twice in one day. The year was 1974, the book was Kingsley Amis’s Ending Up.

I first glimpsed Ending Up in the sunshiny window of a little bookstore in Boston’s Back Bay. It was a new arrival. I was an undergrad, living on a frayed budget, and I rarely bought hardcovers. Not a lot of pages for so extravagant a purchase—176—but I was charmed by the book’s first sentence: “‘How’s your leg this morning, Bernard?’ asked Adela Bastable.” How could any book that began with such confident inhospitality and dreariness fail to be good?

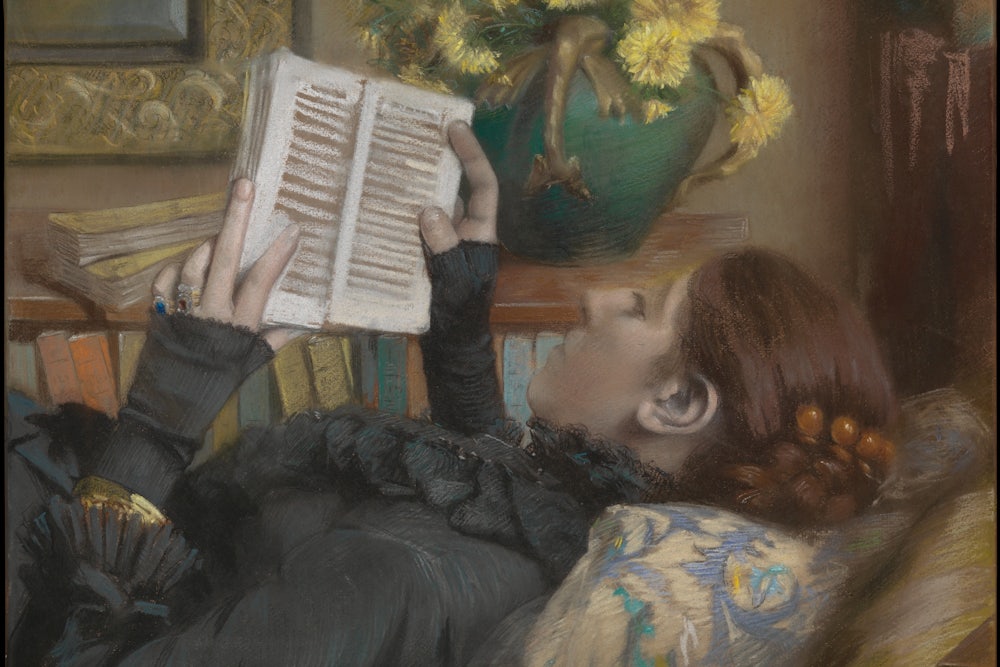

I started it on the subway, making my clanking way back to the quiet of my dorm room, where I curled up and finished it in the late afternoon, sprawled on my narrow, college-issued, box-springless bed. The inhabitants of Ending Up also slept uncomfortably. They were five in all, tucked into a small house called Tuppeny-Hapenny Cottage: Bernard, Adela, George, Marigold, and alcoholic Shorty (who wasn’t short but was thought to require a nickname indicative of his lower social status). The youngest of them was 70.

They were pensioners—a word that carried for me an alien, vaguely English ring—living in isolation in Suffolk. Poverty, as much as anything, had inspired their cohabitation. They shared memories of World War II and an enduring stoical spirit of wartime rationing and parsing husbandry. Needless to say, their world, with its talk of hemiplegia and nominal aphasia and dementia and aperients, was remote from mine. But pleasingly remote: I’d stepped into a cramped, tacky, rundown, superficially cordial, grievance-infested English household and, fascinated, enchanted, had wound up spending the whole day. Amis’s sentences were funny, chilly, touching. The book closed with a substantial and satisfying, if inaudible, thump.

After a quick and early dorm dinner, I returned to my room. The book lay on the floor where I’d left it, shedding a homey and pawky air of invitation. “How’s your leg this morning, Bernard?”… “Much as it was yesterday morning.” I decided to reread the first chapter. The book’s fantastic, casualty-strewn denouement had blindsided me, and I went back to the early pages seeking clues and foreshadowings I’d missed. Sometime around midnight, I finished Ending Up for the second time.

I linger over the book because, in my wayward and lifelong course of reading, the book annually provides me with a kind of happy anniversary: the sunny autumn day I read a novel twice. Memorable novels have a way of affixing a secondary story to themselves, a plot that touches tangentially, if at all, upon the plot of the book. Sometimes you recall a novel chiefly for the circumstances under which it was absorbed. My first-ever day in Europe, I started Middlemarch over a cappuccino in the shadow of the Coliseum. Or, I finished that one in the lobby at Mass General while waiting to hear how her operation had gone.

One memorable kind of reading may result from a deliberate reinforcement of the scene before you. I brought Room with a View with me to Florence, or, I took Huckleberry Finn on our family rafting trip. But more interesting things will likely happen when a book diverges sharply from your surroundings: I read Proust’s endless dissection of Mme. De Guermante’s dinner party while recovering from stomach flu in a motel in Flint, Michigan. As W. H. Auden noted in choosing to bring a copy of Byron with him to Iceland:

I

can’t read Jefferies on the Wiltshire Downs,

Nor

browse on limericks in a smoking-room;

Who

would try Trollope in cathedral towns,

Or

Marie Stopes inside his mother’s womb?

Most satisfying

of all is when some profound connection is forged that feels both artful and utterly

unlooked for—forever lending a book an air of momentous fatedness. I was carrying Turgenev’s First Love when I met my wife-to-be on a flight from

Phoenix.

John Updike has a lovely evocation of this plot-that-surrounds-the-plot in an early short story, “Walter Briggs.” Driving home at night, Jack and Claire, young parents, struggle to recall the name of a guest encountered back when they, as newlyweds, took jobs at a YMCA family camp. The effort awakens in Jack a chain of reminiscence about those magical and still-childless days of young adulthood:

In the half-hour between work and dinner, while she made the bed within, he had sat outside on a wooden chair, reading in dwindling daylight Don Quixote. It was all he had read that summer, but he had read that, in half-hours, every dusk, and in September cried at the end, when Sancho pleads with his at last sane master to rise from his deathbed and lead another quest, and perhaps they shall find the Lady Dulcinea under some hedge, stripped of her enchanted rags and as fine as any queen.

Jack is weeping for the dying and yet immortal Spanish knight, of course, and for Sancho, his feckless and faithful companion. But even while reposing under Cervantes’s golden spell, Jack is weeping also, in a kind of prospective retrospection, for the loss of those youthful campground days beside his own Dulcinea, his new wife, when her “hand had seemed so small, her height so sweetly adjusted to his, the fact of her waking him so strange.”

It’s one of the keenest and least replaceable pleasures I know—the sense, native to a capacious novel, of existing simultaneously inside two calendars. One plot steadily proceeds and it is called Your Life; it’s the old, ongoing, errand-filled business of your datebook. The other plot is new; it’s called The Novel You’re Reading, and it unfolds with its own errands, its own weather and its own zodiac. Last May, I vowed to get through eight big volumes of Trollope over the summer, and managed to get through five. (A slow reader, I typically fail to finish any reading project on schedule.) Plots intercoiled. Boundaries dissolved and new chapter titles surfaced. One of them, which induced me, too, to peer forward in prospective retrospection, was contentedly called That Crazy Summer I Read the Eight Trollope Novels.

Submit to a big novel’s calendar and you often discover a peculiar thing. At first, it may appear to move quite tardily. It’s as if you’ve gone off to the moon, where a day lasts fourteen earth-days, followed by fourteen unbroken days of night. And yet as you continue to read, months will pass, maybe years, decades. Little Antonie is a “petite eight-year-old in a dress of softly shimmering silk” on the first page of Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks and a proud, bewhiskered fallen aristocrat a mere 640 pages later. Word by word, the book trudges by baby steps. Chapter by chapter, it hurtles along.

With the best big novels, a genuine competition gradually arises, as one colossal calendar contends with another. You’re caught up in your daily life—you’re always caught up in your daily life—but you’re simultaneously enmeshed in an altogether different agenda. It’s Labor Day weekend, and you’re giving your old car an oil change at Jiffylube. Meanwhile, it’s mid-June, 1815, you’re in Thackeray’s Vanity Fair, and Jos Sedley is also dealing with transportation issues, he’s in the town of Waterloo, he’s paying a king’s ransom to secure a horse to flee from the deadly spillover of the battle unfolding on a nearby ridge. When a novel really takes hold, its calendar temporarily reigns and the datebook of your daily life turns diluted and pallid, like the earth under a solar eclipse. In this eerie light it seemingly grows evident how oppressive and tyrannical is that dailiness of yours that often appears so absorbing and satisfying. We’re taught to disdain the phrase escapist fiction, but it turns out that an escape is what your soul all along has been craving. Enter another horological zone—a place of syncopated schedules, modified timepieces—and it feels like a salvation.

The poet Daniel Hall captures some of this in a memorable poem, “Mangosteens,” set in China:

I’d also been reading The Spoils

of Poynton, so slowly the plot seemed to unfold

in

real time. “’Things’ were of course

the

sum of the world,” James tosses out

in

that mock assertive, contradiction-baffling

way

he has, quotation marks gripped like a tweezers

lest

he soil his hands on things…

There’s a genial joke here, about James’s leisurely fastidiousness, but also hints of a charming gratitude. A displaced American in an Asian foreign country immerses himself in a novella set in a European foreign country and the prose possesses the magical effect of merging the two calendars—the personal, the novelistic—until they become one.

For all the slowness associated with Thackeray or Dickens or Trollope, their novels all but inevitably end up racing at a pace that far outstrips the reader, who necessarily trudges along, word by word, while even the most poky novel gallops by on horseback. Perhaps it takes four or five hours to read A Christmas Carol—but in that time you will, chaperoned by the ghosts of Christmas Past and Christmas to Come, traverse many decades. A novel is a natural accelerant. This pattern is so rigid and expected that we scarcely remark it—until some rarity comes along, like Nicholson Baker’s first book, The Mezzanine, to flip this expectation on its head. The “sweep” of Baker’s novel is a single lunch hour, and its most eventful transaction is the purchase of a pair of shoelaces. The book takes longer to read than the events it chronicles; we’ve entered a mirror world where the literary calendar moves more languorously than the personal one. You, the reader, like Dorian Gray’s portrait, are aging more rapidly than the characters you’re reflecting upon.

You might argue that literary characters never age, never change. Nabokov makes this point quite wittily in Lolita: “No matter how many times we reopen King Lear, never shall we find the good king banging his tankard in high revelry, all woes forgotten, at a jolly reunion with all three daughters and their lapdogs.” By this light, to watch a play, to read a novel, is to pose a flesh-and-blood audience before subjects carved in granite. While we in the audience identify and empathize with all the “changes” the often tragedy-laden characters endure, we alter and they do not.

Yet by another light the characters do change, the plot continues metamorphosing. Though my first two readings of Ending Up occurred on the same day, the novel was already a different creature the second time around. The first reading of any truly good novel often winds up becoming a mere rehearsal. Now that you’ve planted the full arc of the story in your head, and a preliminary sense of how its chapter-parts relate to its plot-whole, you can progress through it with an informed, focused pleasure. You’re a wiser reader the second time around—you might say, a better reader. Of course the first time you’re more wonder-struck—you might likewise say, a better reader. But if you can be both in one day, you’re something else again. Now you’ve really hit it.