In John Waters’s film Female Trouble, Aunt Ida (played by ex-barmaid Edith Massey) reveals a sentiment that, I suspect, she has in common with many queer people: “the world of heterosexuals is a sick and boring life.” It’s not so much that marriage is incompatible with being queer, so much as it seems to interfere with all the fun parts: prolific sexual relationships negotiated outside an established set of mores, staying out late instead of running home to pick up children, living with your friends and lovers until everyone had died or moved away, the wholesale rejection of Red-State America. The world of John Waters is, after all, vivid portrayal of queer life as the antithesis of the neat, moral, and prudish side of America.

Perhaps it’s queer culture’s adherence to, or at least embrace of, deviance that explains the ambivalence many of us felt about same-sex marriage. Masha Gessen, who has been married three times and for three very different reasons, has said of marriage: “It is a terrible, formulaic contract. It enforces unrealistic expectations and obligations. It obliterates lived reality.” Compared to fighting for protection in the workplace, hate crime laws, prison safety, youth homelessness, and representation in government, marriage is a straight thing to fight for. Andrew Sullivan—who provided one of the earliest arguments for gay marriage—pointed out in 1989 that it was a case so conservative that “Burke could have written a powerful case for it.”

However, the scruples of collective identity and inheritance seem a hollow luxury when placed next to the struggles of couples who found themselves legally ineligible for marriage. Janice Langbehn, along with three of her children, was barred from seeing her dying partner at a hospital in Florida on grounds that she was not a blood-relative or spouse. Edith Windsor—the plaintiff for the case which would eventually overturn the Defense of Marriage Act—was forced to pay nearly half a million dollars in estate taxes on the inheritance her wife left her. When the head of the Human Rights Coalition suggested at a meeting that same-sex marriage was something better put off until later, Windsor objected: “I’m 77 years old, and I can’t wait!”

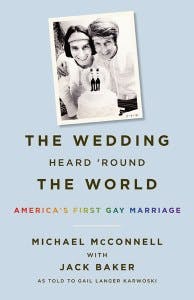

Waiting was something Michael McConnell and Jack Baker endured for over four decades. On May 18th, 1970, the couple applied for their first marriage license at the Hennepin County Courthouse, and began a lifelong battle with clerks, lawyers, judges, the military, state and federal governments, adoption agencies and the IRS for the legitimacy and recognition of their marriage. McConnell has now told their story, with the aid of children’s book author Gail Langer Karwoski, in a memoir published by the University of Minnesota Press titled The Wedding Heard ‘Round the World. Although same-sex marriage became politically viable relatively quickly once it had become a national issue, this book serves as a gentle reminder that there were couples plotting this victory long, long before a consensus formed around marriage equality.

McConnell and Baker met in 1966 at a gay dance in Oklahoma, fell in love, moved in together, and within a year began to plan their marriage. For that, McConnell remembers, “We needed to know more about the law.” Baker applied to law school at the University of Minnesota and was accepted, moving there first while McConnell finished his contract at a library in Oklahoma. After their first attempt to marry, in 1970, was rejected, they took the unusual route of having McConnell adopt Baker, changing his name to the gender ambiguous “Pat Lyn.” A year later, at the Blue Earth County Courthouse, they applied for a second marriage license, which was granted when the clerk assumed the couple happened to have a shared surname. It’s unclear from the book if this license was objected to on grounds that the couple were, technically, father and son. It is clear that, though their license was accepted, neither the IRS, military, nor virtually any other state institution would recognize it until much later.

McConnell’s memoir is for the most part an intimate portrait of suburban gay life in the 60s and 70s. McConnell and Baker attend dances in barns, churches, and university campuses; a wholesome counterpoint to the kinky, bohemian New York of Mapplethorpe and Warhol. Their wedding outfits were bell-bottomed slacks, pullover shirts of “drapey polyester fabric,” and macramé headbands. Meanwhile the book has plenty of moment of overshare: McConnell has an unwelcome habit of surprising the reader with breathless anecdotes about his sex life or, as he puts it “making love.” (About his first night with his future husband: “We didn’t speak; we both seemed to understand that this was a night to explore and savor. We kissed. Slowly. No need to rush or grab. I slipped out of my shirt and jeans and slid across the cool sheets into his warm arms.”)

It is more difficult, however, to accept the book’s central thesis that “marriage is the central goal of the gay rights movement.” If the Stonewall Riots, the assassination of Harvey Milk, the use of sodomy laws to imprison homosexuals until Lawrence v. Texas, the rise of ACT UP, or any of the other now familiar events in gay rights history affected him, none were strong enough to be included in his memoir. McConnell does, in passing, comment on the AIDS epidemic. His anecdotes about police raids at gay dances, opening a home for gay men suffering from drug addiction and poverty, and fighting against cases of job and benefit discrimination, indicate his awareness of gay rights as a coalition of interests. But his heart doesn’t seem in it. The entire narrative of gay rights is couched in the language of straight 1950s relationships and middle class aspirations: McConnell’s childhood awareness that “girls pictured themselves in a sparkling new house with a handsome husband—so did I” along with the fact that “Mother and Daddy always told us McConnell kids: we are as good as anyone else.”

McConnell in fact meets with a grave case of discrimination in his working life, and though he is indignant, he does not respond with the same relentless pursuit of rectification. Early in his career McConnell applied for and was offered a position at the University of Minnesota as a librarian. However, after leaving his former job and relocating from Oklahoma to Minnesota, his offer was rescinded by the Board of Regents which decided that his “personal conduct…[was] not consistent with the best interest of the University.” Personal conduct was, of course, the euphemism for his decision to live openly as a gay man cohabiting with his partner. Though Baker and McConnell worked to challenge the University’s decision, he never concedes that fighting workplace discrimination was as important a goal as marriage equality in the gay rights movement. After Baker and McConnell are married, workplace discrimination fades into the background and comfortable middle-age sets in. Tellingly, it is still legal to discriminate against an employee on the basis of sexual orientation in 28 states.

McConnell’s perspective, like that of many gay men from comfortable backgrounds, can occasionally seem closer to that of someone feeling robbed of an idealized life, rather than one of struggle against adversity. He talks about coming to terms with the fact that “realistically, we stood a very slim chance of adopting a healthy, American-born Caucasian baby” and resolving to love a non-white, foreign, baby with health problems. Of course, it’s also a reminder of how many very real difficulties still beset same sex couples that even the supposedly realistic hope turns out to be unrealistic: after decades of waiting, no child of any sort was granted to McConnell and Baker. Adoption agencies, which didn’t recognize their marriage, viewed their applications as the least desirable adoptive parent category: unmarried men.

There are, too, inescapably sad letters in one chapter, sent to McConnell and Baker after a Look magazine profile by gay men isolated in small towns: one pleads for help since “the loneliness and depression are getting to me” and the other that “some of us will never have that kind of courage” to live openly. Much of Jack Baker’s family never accepted his sexuality, and McConnell’s ambitions to work as an academic librarian were hindered by prejudice. After being rejected by the University of Minnesota, McConnell accepted a much lower position at a local public library. For all their struggling and researching, campaigning and litigating—and, sometimes, success—Michael McConnell and Jack Baker came to know first that gay life in a straight world was ultimately a life of coming to terms with limitations, caused purely by who you love.

My boyfriend, an Indonesian photographer, and I have been together for several years in what is generally a comfortable, happy, stable relationship. In 2013 the Supreme Court’s decision for United States v. Windsor overturned the Defense of Marriage Act, making same-sex marriages issued by states legitimate at the Federal Level. Two years later, in Obergefell v. Hodges, the Supreme Court decided that same-sex marriage was guaranteed by the due process and equal protection clauses of the Constitution. The pace of change felt unexpectedly swift, even for predictably optimistic activists, who had seen voters heartily approve state-level bans on gay marriage just a few years ago.

Neither of us grew up anticipating marriage: it is mutually acknowledged that the prospect of exchanging vows, wearing matching tuxedos, and using the word “husband” on a daily basis is embarrassing. However, every year his immigration status must be re-negotiated and threatens to place 10,000 miles between us. Jakarta is not a welcoming environment for openly gay couples. My feelings of ambivalence about marriage evaporate when all of a sudden a precious thing to me is placed in the hands of immigration services. Despite the rhetoric of marriage equality being about love, marriage itself is still, in essence, about cold legal rights—the things that protect us when something as delicate as a relationship comes under the scrutiny of an unblinking state. McConnell and Baker may have been married for love, but for people like Masha Gessen, who married to protect her partner and children from life in Putin’s Russia, and for me, marriage will always be a choice between the amorphous nature of queer relationships and the protection of the state against the dangers of being legally single for your whole life.

Of course our situation would hardly be noteworthy if we weren’t a gay couple. Foreseeing and planning on the legal, financial, and political benefits of marriage is simply part of the calculations straight couples in long-term relationships make. But in the course of my relationship, I’ve gone from having nothing to gain from marriage to potentially losing a lot by ignoring it. My generation has gone from establishing courtship, sex, monogamy, and cohabitation on our own terms as outsiders, to having to accept we’re now a part of the same structured, tradition-laden, legally-sanctioned world as everyone else. Love, so the cliché goes, is about compromise. For me, perhaps that means making some concessions to the boring, married life of heterosexuals.