Up until the 1970s, British art criticism was predicated on the idea of connoisseurship. Critics like Kenneth Clark and Bernard Berenson—both of whom one Financial Times journalist described as being “unashamedly elitist in both their work and their lives”—were more concerned with matters of attribution, authentication and technique, than with a painting’s relation to a common person’s life. Race, class, gender: these weren’t seen as critical concerns. Aesthetics was ascribed holy importance, and the critic’s role was to help us pray.

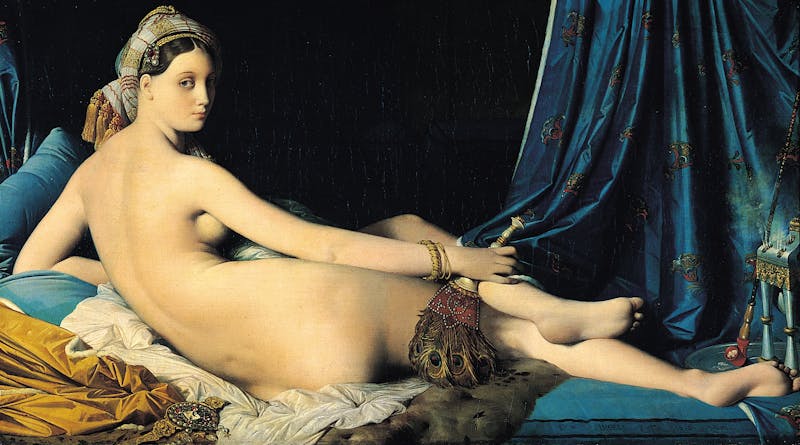

When Ways of Seeing premiered on the BBC in 1972, it was radical both in style and content. At a time when arts programming generally featured suited men pontificating before fireplaces in their vacation villas, Ways was filmed at an electric goods warehouse, and was anchored by the longhaired, Aztec-print-wearing, leftist intellectual John Berger, who addressed the camera in an equal and non-elitist tone. At a time when critics only concerned themselves with “aesthetics,” Berger set about revealing the capitalist and colonial ideologies behind much western art, as well as putting forth a major feminist critique of it. Ways of Seeing was pioneering for the ease with which it moved between analyzing the highbrow (e.g. the great masters) and the lowbrow (e.g. advertisements), more importantly, for how it kicked down the supposed distinction between the two. In one memorable scene, Berger compared Ingres’s Grande Odalisque to a photograph in a porno. They were both arranged, in his opinion, to depict “a woman’s body to the man looking at the picture. This picture is made to appeal to his sexuality. It has nothing to do with her sexuality.”

Ways

of Seeing had a limited

impact when it first aired. The BBC broadcast its first episode at a very late

hour —“They didn’t trust us,” Berger later lamented in an interview—but after

observing its turn-off rates, which were minimal compared to similar shows, the

BBC agreed to screen the next three episodes earlier in the evening. The

initial media response was similarly modest. “There were few reviews,” producer

Mike Dibb reflected in an interview, “The Radio Times did an interview with

John, and didn’t publish it.” Slowly, however, the show’s reputation, and

Berger’s, began to grow. “Ways Of Seeing

is an eye-opener,” one Sunday Times

critic wrote, “by concentrating on how we look at paintings ... he will almost

certainly change the way you look at pictures.”

John Berger is rightly lionized for Ways of Seeing. But the series, in fact, only represents a small part of his larger body of writing. Since the 50s, Berger has regularly produced fiction, nonfiction, polemics, art criticism, screenplays, drama, poetry, and many many unclassifiable books. These include collaborations with photographers, polemics on the migrant experience, personal essays that are really political essays, written correspondences with personalities ranging from Cartier Bresson to Subcomandante Marcos, reflections of having his cataract removed, a book that imagines drawings by Spinoza.

Berger was a painter before he became a writer. Born in 1926, he briefly served in the army before enrolling in London’s Chelsea School of Art in his early 20s. For a few years after that he exhibited around the city. But political events brought his painting career to a premature end. “The reason I stopped painting at the end of the 40s,” he says in a recent interview:

was what was happening in the world: the threat, above all the threat of nuclear war. This was before the Soviet Union had parity. This threat was so pressing, that painting pictures—that somebody would go hang up on the wall—seemed… [dimissive hand gestures] But to write, urgently, in the press, anywhere, everywhere, seemed so necessary.

Thus, Berger dropped out of art school and channeled his political energy into art criticism and fiction.

Berger’s debut novel, A Painter of Our Time (1958) received such vitriolic criticism—from the poet Stephen Spender, amongst others—for its Soviet sympathies, that its publishers ended up having to withdraw it. His art criticism, which he began publishing in The New Statesman and Tribune, likewise regularly met with outrage from readers.

Their outraged stemmed from the fact that Berger, who was explicitly Marxist in his views, was willing to criticize big personalities—including Henry Moore, Francis Bacon, and Pablo Picasso—who he saw as producing mystifications, not art. On the flip side, he championed continental painters like Ferdinand Leger and Oskar Kokoschka, as well as older masters like Jean-François Millet and Gustave Courbet, who offered more uncynical models for the future.

Berger’s essays from the ‘50s eventually made their way into his debut collection Permanent Red (1960). (This book’s title reveals enough about his political slant.) There have been several more collections as well as full-length books of art criticism since. These include, The Success and Failure of Picasso (1965), Art and Revolution: Ernst Neizvestny And the Role of the Artist in the U.S.S.R (1969), The Moment of Cubism and Other Essays (1969), The Look of Things: Selected Essays and Articles (1972), About Looking (1980), The Sense of Sight (1993), The White Bird, (1985), Understanding A Photograph (2013).

2000 saw the publication of his Selected Essays, a 600-page tome that provides a generous selection of all his 20th century work. Though Berger has continued to write on art since then, he is not a full-time journalist (he hasn’t been one for decades) and there hasn’t been a Bolaño-style outburst of late writing.

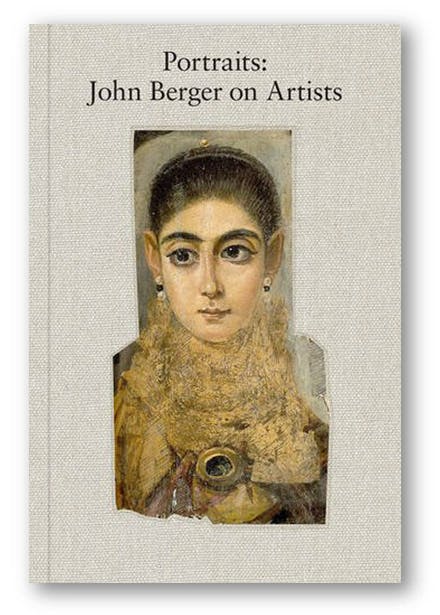

Berger’s newest book doesn’t contain his latest

writing. Portraits, recently

published by Verso, is a remixing of Berger’s past work, a 502-page collection ordered by chronology of the artists Berger has considered in his fifty-year

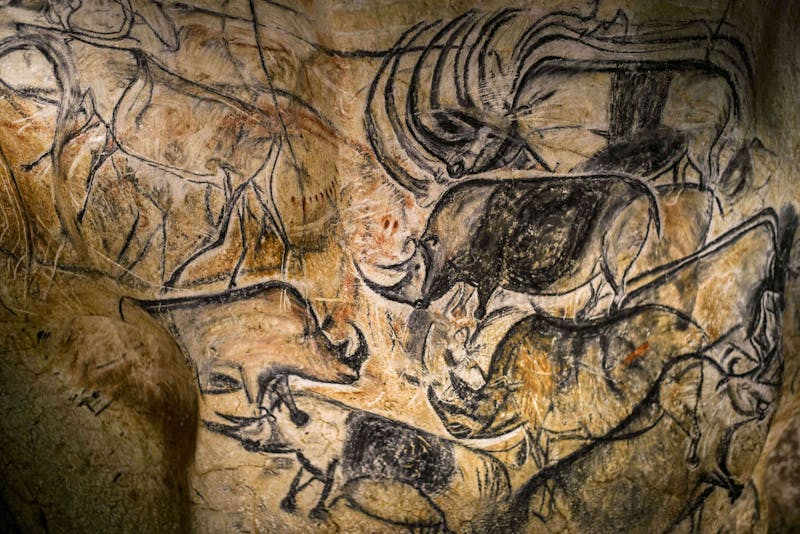

career as a critic. The first essay begins around 30,000 BC, with an analysis

of the Chauvet Cave paintings, and the final essay considers Randa Mdah, a

Palestinian sculptor born in 1983. In between, we find work on almost every

major painter who lived after 1400—from Pieter Bruegel the Elder and Hieronymus

Bosch, to Caravaggio and Frans Hals, all the way through the nineteenth and

twentieth centuries with J.M.W. Turner, Edgar Degas, Pablo Picasso, and Jean-Michel

Basquiat. What’s astonishing is that like Ways

of Seeing, Portraits also manages

to rearrange the entire canon of western art.

On one level, Portraits allows us to see Berger re-evaluate individual artists. Berger has written multiple essays about the same artist several times in his long career. When this is the case, Portraits publishes these essays back to back. Portraits’s entry on Francis Bacon, for example, features three different essays, the first written in 1952, the last in 2008.

Berger’s first evaluation of Bacon, a 1952 review for the New Statesman was largely negative. He extolled Bacon’s dramatic prowess, but argued that the horror depicted in his work was unrealistic and in fact chic. “The horror,” of Bacon’s paintings is stimulating, he wrote, “because it is remote, because it belongs to a life removed from the natural world.” Twenty years on, his evaluation was even harsher. In an essay titled “Francis Bacon and Walt Disney,” Berger compared Britain’s most famous post-war painter with America’s commercial hero, arguing that “Both men make propositions about the alienated behavior of our societies; and both, in a different way, persuade the viewer to accept what is.” But his final essay, written in 2002, shows a stunning reversal of his critical opinion. Bacon’s bleak vision, Berger writes:

was nourished and haunted by the melodramas of a very provincial bohemian circle, with which nobody gave a fuck about what was happening elsewhere. And yet …. and yet the pitiless world Bacon conjured up and tried to exorcise has turned out to be prophetic.

This statement doesn’t just represent a wavering of personal subjectivity, rather, it is an admission that the world itself has changed, and with it, Berger’s aesthetic subjectivity. This synthesis of aesthetics and history takes us to the heart of Portraits’ art critical project.

Formally, Portraits resembles a survey of canonical western art. It is arranged in chronological order, and though there are a few outsider choices (Indian artist F.N. Souza, Scandinavian sculptor Sven Bolmberg) the names you encounter here are in general those you’re likely to find in most art history textbooks. What separates Portraits from other art history books, however, is Berger’s conception of history itself. Unlike most art historians, who assume that the present moment represents a state of maximum enlightenment, Berger repeatedly admits—and even draws our attention to the fact—that his judgments are colored by historical subjectivity. As he writes in “Between Two Colmars,” first published in About Looking in 1980,

It is commonplace that the significance of a work of art changes as it survives. Usually however, this knowledge is used to distinguish between “them” (in the past) and “us” (now). There is a tendency to picture them and their reactions to art as being embedded in history, and at the same time to credit ourselves with an over-view, looking across from what we treat as the summit of history…. This is illusion. There is no exemption from history.

In other words, Berger doesn’t view art history as something that happened, rather as something that

continues to happen. Consequently, he finds all absolute judgments (à la Harold

Bloom) to be futile. Following this realization, Berger decides to firmly root

himself in the present and instead

focus on why a particular artwork—be it from 30,000 BC, or 2010—appeals to us today, under present historical

conditions.

This is why Portraits is unlike most other books of art history. While most

scholars attempt to contribute (or remove) a few new names to the standard art

historical story, Berger wants to retell

the entire story itself. The retelling does not include new artists so much as

it entails a fundamental change in our relation

to each artist. Consider, for example, the opening paragraph of his essay

on Egyptian portrait painters from 30,000 BC:

These are the earliest painted portraits that have survived…Why then do they strike us today as being so immediate? … Why is their look more contemporary than any look to be found in the rest of the two millennia of traditional European art that followed them? The Fayum portraits touch us, as if they had painted last month. Why? This is the riddle.

Berger wants us to understand why 50,000-year-old paintings are relevant right now. On one hand, this approach makes Berger’s essays feel very urgent. On the other, it shows us that art history, like all history, has to be continually rewritten. Only when the historian understands the needs of the present can he elucidate how these needs are answered by the art of the past.

The 74 essays included in Portraits take on an exhilarating

variety of forms. Berger’s essay on Caravaggio, for example, is written as a

wrenching love letter from Berger to his wife. There is an exchange of letters

between Berger and his daughter about looking at the paintings of Titian. A

Holbein essay includes discussions on Dostoyevsky, Courbet, and Rothko—but none

on Holbein himself, because Berger went to the wrong museum. The life of Franz

Hals is summarized as a three-act play. The sculptures of Degas are the subject

of a poem. Interestingly, we even get excerpts from Berger’s fiction: the protagonists

from his 1958 first novel A

Painter of Our Time meet at a Goya exhibition; Corker of his 1964 novel Corker’s

Freedom is seen

drawing The Maja Undressed.

This formal ingenuity points towards a

more general trait of Berger’s criticism—it often reads like a story. “I often

think,” Berger said in an interview with Geoff Dyer in 1984, “that even when

I was writing on art, it was really a way of story-telling.” Indeed a majority

of the entries in Portraits make riveting

reading as narratives or character sketches.

Stories also lie at the heart of Berger’s

understanding or his engagement with

an artwork. “Having looked at a work of art,” he writes in Portraits’ prologue:

I leave the museum or gallery in which it is on display, and tentatively enter the studio in which it was made. And there I wait in the hope of learning something of the story of its making. Of the hopes, of the choices, of the mistakes, of the discoveries implicit in that story. I talk to myself, I remember the world outside the studio, and I address the artist whom I maybe know, or who may have died centuries ago... Occasionally there’s a new space to puzzle both of us. Occasionally there’s a vision which makes us both gasp—gasp as one does before a revelation.

For Berger, paintings are testaments to human expressions or stories of human struggle—they are not simply objects to be admired. It is for this reason that he continually pulls the real, outside world into his criticism.

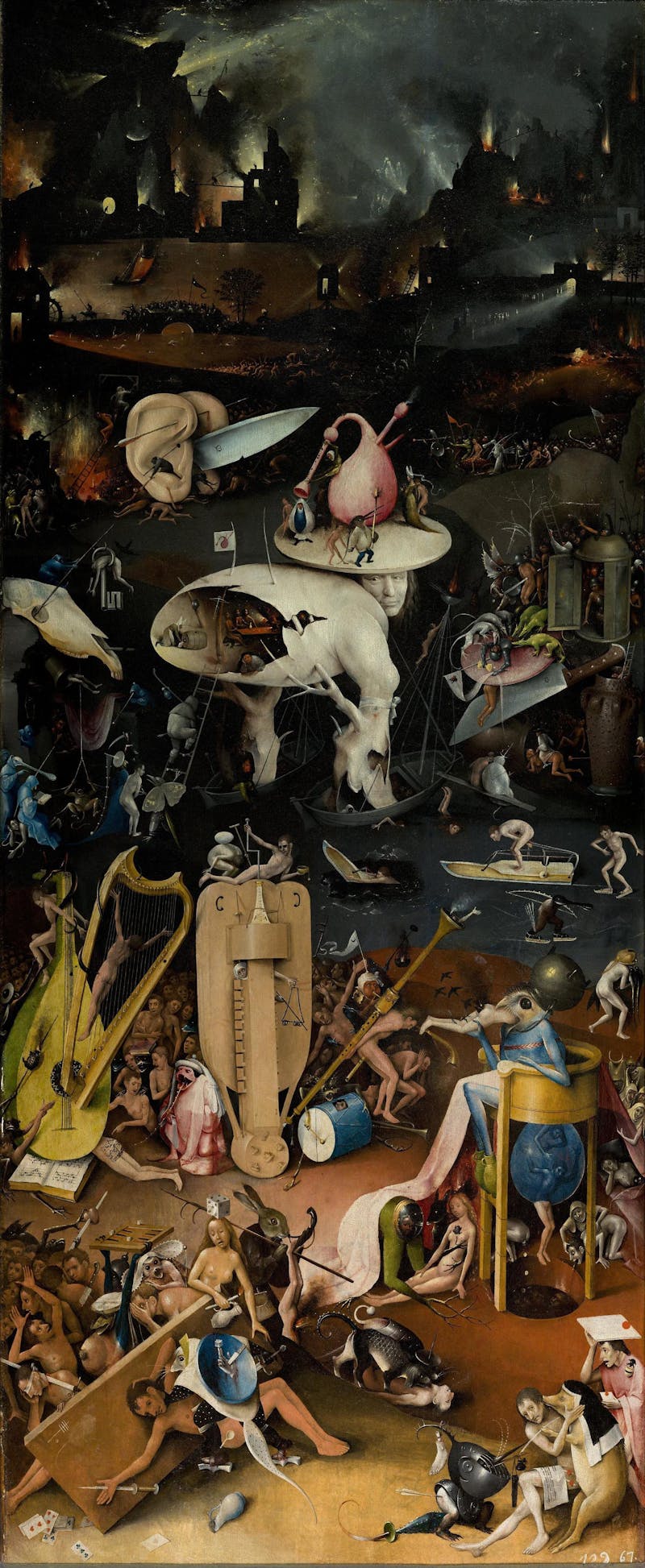

“Leave the museum. Go the emergency department of the hospital,” Berger writes in his essay on Rembrandt, and it is only in the hospital that we begin to understand how Rembrandt’s captured our corporeal existence, how his calculated dislocation of proportion reflected the “sentient body’s awareness of itself.” Similarly, in his discussion of the “Hell” panel in Hieronymous Bosch’s Millennium Triptych, Berger observes that:

There are no horizons there. There is no continuity between actions... There is only the clamour of the disparate, fragmentary present… Nothing flows through: everything interrupts. There is a kind of spatial delirium. Compare this space to what one sees in the average publicity slot, or in a typical CNN news bulletin, or any mass media news commentary. There is a comparable incoherence, a comparable wilderness of separate excitements, a similar frenzy.

Here he has revealed something vital about Hieronymous Bosch, about modern life, and—most importantly—about how Bosch can help us and navigate modern life. In its bridging of time periods, it also reveals Berger’s acute historical awareness.

“All history is contemporary history,” begins a famous paragraph from G, his 1972 novel that won the Man Booker that year. “For even when the events which the historian studies are events that happened in the distant past, the condition of their being historically known is that they should vibrate in the historian’s mind.” History is always vibrating in Berger’s mind. He knows that history must be understood (imbibed, really) if we are to escape the contingencies of our present and engage with art of the past. And he does his best to share this historical awareness with us. This is why he interrupts a discussion on cave paintings of animals to provide a detailed and moving account of taking his cows out to graze. (For the past 38 years, Berger has lived in Quincy, a town of about 100 people in the French Alps near Mont Blanc.) The cows are brought home, and he returns to the cave art. Suddenly we are struck by their impact. It is the pasture that helped under us under the paintings. Through simple, moving narration, Berger has helped us surpass 5000 years of history, and Portraits is crisscrossed with these bridges between the present and the past.

Art, human expression, historical

awareness, material awareness—all are aspects of Berger’s political beliefs.

“For twenty years,” he wrote in The

Moment of Cubism

(1969), I have searched like Diogenes for a true lover of

art: if I had found one I would have been forced to abandon as superficial, as

an act of bad faith, my own regard for art which is constantly and openly

political. I have never found one.”

Berger is not political in a reductionist or dogmatic way. For him, all great art, and all noble politics, is created as a response to life. The great masters don’t interest him simply because they are great. (Art collectors, even the most discriminating ones, he notes, have a “manic obsession to prove that everything he has bought is incomparably great and that anybody who in any way questions this is an ignorant scoundrel.”) Berger studies their visions to learn something about survival—not just his own, but the also the survival of a world where people can live free and meaningful lives.

In an otherwise unremarkable introduction

to the Selected Essays, Geoff Dyer

isolates Berger’s inextricable concerns about art and politics as being “the

enduring mystery of great art and the lived experience of the oppressed.” This

formulation is exactly right, and it is most vividly represented in Berger’s essay

on Caravaggio, originally published in Our

Faces, My Heart, Brief As Photos

(2005) and reprinted here in Portraits.

Berger agrees with the traditional art-historical view that Caravaggio was “one

of the great innovating masters of chiaroscuro, and a forerunner of the light

and shade later used by Rembrandt,” but he is not interested in simply entering

an art-historical dialogue, so he instead opens a metaphysical and political

discussion. Berger considers Caravaggio to be “first painter of life as

experienced by the popolaccio [the

urban poor]” and the only painter who did not depict the poor for others, but

actually shared the popolaccio’s

vision. Following this intuition, Berger concludes that Caravaggio’s

chiaroscuro wasn’t simply a technical innovation. For Caravaggio:

Light and shade, as he imagined and saw them, had a deeply personal meaning, inextricably entwined with his desires and his instinct for survival. And it is by this, not by any art-historical logic, that his art is linked with the underworld. His chiaroscuro allowed him to banish daylight. Shadows, he felt, offered shelter as can four walls and a roof.

The argument that follows blends social history, close aesthetic analysis, and psychologizing. Berger, who spent much time with the urban poor—his nonfiction book A Seventh Man (1975) was a sustained exploration of the plight of migrant laborers in metropolises across Europe—has noticed that those “who live precariously and are habitually crowded together develop a phobia about open spaces which transforms their frustrating lack of space and privacy into something reassuring.” He thinks Caravaggio shares this fear. He thus convincingly argues that Caravaggio’s deployment of light, the contrasting ways in which he paints outdoor and indoor scenes, the particular drama of his paintings, all astutely reflect the urban poor’s experience of the world.

The enduring mystery and relevance of art;

the lived experience, both of the free and the oppressed; by combining these

interests, Berger’s art criticism

transcends its genre to become a very rare thing—literature.