Following in the illustrious footsteps of the likes of Bela Lugosi, Lon Chaney Jr, Peter Cushing and Gene Wilder, James McAvoy plays the mad scientist Victor Frankenstein in the latest film version of Mary Shelley’s gothic novel, this time with Daniel Radcliffe in tow as his assistant Igor.

The film promises all the lightning, grave-robbing, and fantastical elements we’ve come to expect from the story. But it also has echoes of a real scientist, working mysteriously in the heart of the English countryside.

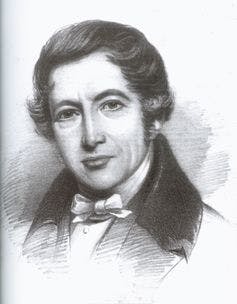

In the early years of the 19th century, strange stories began to be told about an isolated Somerset country house in the Quantock Hills. Its owner, Andrew Crosse, was known to locals as the “Wizard of the Quantocks”.

Crosse, also nicknamed “the thunder and lightning man”—and, more simply, “the electrician”—was born in 1784 and was an early pioneer in the study of electricity. He inherited Fyne Court in 1805 and transformed the house and wooded grounds into a laboratory for his experiments in investigating atmospheric electrical charges and the potential creative power of lightning strikes. Tim Mowl and I did some archaeological work in the grounds recently and traces of the garden laboratory survive today.

Crosse’s revelations on the power of electricity challenged orthodox creation theories: Here was a power that could be controlled, an alternative to divine power. Mary Shelley’s diaries reveal that in 1814 she and her husband Percy Bysshe Shelley attended a lecture that Crosse, “the thunder and lightning man”, delivered in London.

Mary published Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus in 1818, featuring a “Modern Prometheus” who defied the Gods by creating a monster reanimated by the power of electricity. Could Andrew Crosse have inspired the real Frankenstein?

Harnessing lightning bolts

Spending the family inheritance on scientific equipment, Crosse constructed a complex register for measuring the strength of electrical charges in the air, not just during thunderstorms, but in all weather conditions. Crosse used a third of a mile of copper wire, threaded from poles attached to the tallest trees to create a gathering web and connected this down to a battery of 50 Leyden jars stored, apparently, in the organ loft of Fyne Court’s music room. Recent geophysical work has demonstrated the presence of buildings beneath the modern car park which may also have formed part of the laboratory complex.

When atmospheric conditions were favourable the in-surge of electrical power was so great that batteries would charge and discharge each time with a monstrous flash and a massive explosion of sound. What impressed visitors was the way in which Crosse manipulated the deadly forces with an insulated rod, directing them into batteries and experimental jars, or out into the earth.

The flashes and explosions gained Crosse local notoriety—as one visitor reported:

You can’t go near his cursed house at night without danger of your life; them as have been there have seen devils, all surrounded by lightning, dancing on the wires that he has put up round his grounds.

But in the wider world of science he was a respectable member of the London Electrical Society, working at a time when it was being suggested that electricity was the primal creative force behind not only all living things, but also inanimate materials. Michael Faraday, a leading experimental physicist and pioneer of electricity, was a close friend of Crosse, and Benjamin Franklin—whose experiments with kites and lightning flashes have obvious links with Crosse’s work—was one of his father’s acquaintances.

Vital forces

On December 28 1814, Mary Shelley attended a lecture that Crosse gave at Garnerin’s London lecture rooms, where he gave a vivid account of the explosive fires that he, like Prometheus, brought down from the heavens. Mary’s journal entry provides proof that she attended Crosse’s presentation:

Shelley and Clary out all the morning. Read French Revolution in the evening. Shelley & I go to Gray’s Inn to get Hogg: he is not there; go to Arundel Street; can’t find him. Go to Garnerin’s. Lecture on Electricity; the gasses & the Phantasmagoria, return at ½ past nine Shelley goes to sleep.

In the course of the lecture, Crosse explained how he tapped into and controlled thunderstorms, which must have seemed a case of humanity equalling or even cheating the gods. Such claims were combined with hints that electricity could, when controlled as Crosse could control it, heal the sick. It was only a short leap on Mary Shelley’s part to advance from cures for rheumatism and hangovers to invent that ugly and dangerous—yet tragic—monster of Frankenstein’s devising.

Crosse scandalised conservative critics when (in the 1830s, long after the publication of Frankenstein) he claimed to have produced living creatures in his electrical experiments: beetles which he named “Acarus crossii” after himself.

Andrew Crosse is buried under an obelisk shaped tombstone in Broomfield churchyard—in an area usually reserved for outsiders and miscreants, which may indicate how the local parishioners viewed him. His inscription describes his as: “Humble towards God and Kind to his Fellow Creatures”. Yet he was a man who, through his scientific achievements, was more challenging than humble when it comes to the almighty.

Mary Shelley’s book was a cynical but imaginative advance on the thunder flashes and fire balls that Crosse produced at Fyne Court and described in his lecture. Like Crosse’s electrical experiments, Shelley’s Modern Prometheus could be taken as a direct challenge to God. They both offered an alternative theory of creation, one which the writer and the scientist seem to have shared on that December evening in 1814.

![]() This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.