Time collapses around local tragedy. Sitting in a tiny station in a small town in Wisconsin, waiting to catch a train home for Christmas, I struck up a conversation with a man who had lived in the area for his entire life. When I told him I was reviewing Making a Murderer, a new a documentary series about the Steven Avery case up in Manitowoc County, his face fell. “Ohh,” he said quietly, glancing away. “Steven Avery. I think he was sick to begin with. And then getting his nephew involved…” For him, the memory was not just fresh, but painful.

I chattered a little about my own theories, the way people far removed from a crime—the people who have not seen it on their local news night after night for months or years; the people who don’t associate it with a town they might have grown up near, a family they might have known—tend to do. I had watched the series with my friend Mary Jo, who grew up in yet another small town in Wisconsin. Somewhere in the middle she excitedly texted one of her friends about the case. This was a woman who, Mary Jo said, always loved to discuss true crime narratives with her, cultivating theories and arguments and doubts. Not this time. Mary Jo’s friend felt connected to the case, as so many small-town Wisconsinites do. It was a story that struck too close to home.

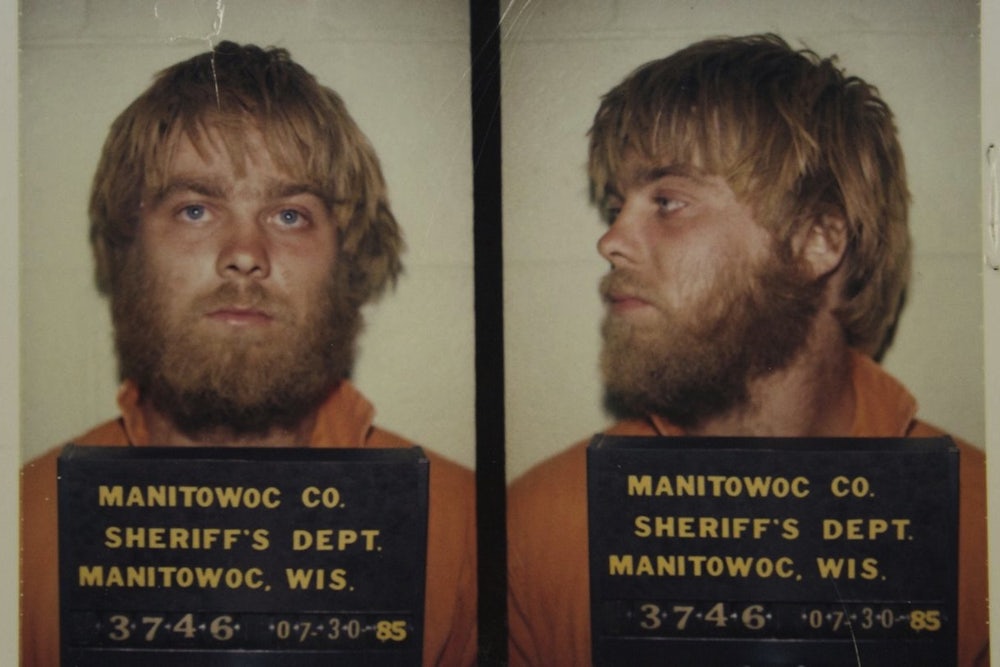

Making a Murderer, which filmmakers Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos made over the span of a decade, unfolds in ten hour-long episodes, pulling away from the local narrative as it presents, in detail, the inconsistencies and distortions in the widely-accepted version of events. The series begins where most stories of its kind can only hope to end: with an exoneration. In 2003, Steven Avery was released from prison, after serving eighteen years for a brutal sexual assault that the Wisconsin Innocence Project finally helped to prove he did not commit. In the first moments of Making a Murderer, before we can entertain questions about his pathology or menace, we see Steven Avery’s euphoria. His family surrounds him. Everyone is overwhelmed with joy. Backed by a skilled legal team, he brings a civil suit against Manitowoc County, at first seeking damages of $400,000—a figure that eventually climbed to $36 million. Governor Jim Doyle is poised to sign into a law a justice reform bill bearing Avery’s name. Then, less than two years after his release, he is arrested for murder.

Making a Murderer does not present us with the type of crime narrative we’re used to encountering on TV: the forty-five minute template that begins with the beautiful body of the dead girl and ends with the evildoer slapped into cuffs. Whether the story is real or fictional doesn’t matter: both evergreen ratings staples like the CSI and Law & Order franchises and their “true crime” counterparts (Serial Thriller, A Crime to Remember, Southern Fried Homicide) flatten every case into a series of reliable archetypes. If Making a Murderer followed this guide, then we would not begin with Steven Avery. We would begin, instead, with the disappearance of twenty-five-year-old Teresa Halbach, who went missing on Halloween 2005. Working as a photographer for Auto Trader Magazine, her last appointment for that day was with Steven Avery, who was working at his family’s auto salvage yard; she was there to take pictures of a van they were selling. After her disappearance, investigators and volunteers conducted an extensive eight-day search of the property, culminating in their discovery of Teresa Halbach’s remains in a burn barrel on the Avery family’s property. Steven Avery was charged with her murder.

The man who had once been “a living symbol of how a system could unfairly send someone away” was now once again the subject of deep suspicion. “I felt uncomfortable allowing [him] to remain on the street” an investigator told Manitowoc County’s local Fox affiliate during the investigation. The evidence that would link him to Halbach’s death had not yet been tested, but this didn’t seem to matter. Steven Avery was dangerous, and the state’s only mistake had not been in convicting him the first time around, but in allowing him to go free. “It’s this simple,” Representative Mark Gundrum said, “Once Steven Avery is accused of this murder…as much as you mentally want to give the benefit of the doubt to him, it becomes impossible.” Mark Gundrum had been one of the founders of the Avery Task Force, which was intended to prevent wrongful convictions of the kind Avery has suffered. He had been determined to learn from Avery’s story, rather than hide it. If Avery was guilty until proven innocent in Gundrum’s eyes, then what chance did he have with others?

For people who watched Steven Avery’s story unfold in their backyard, it must have been all but impossible to avoid seeing him as a symbol: first of their community’s shame at imprisoning an innocent man, and then of their shame at being fooled by a criminal. But somehow, Steven Avery’s guilt made him seem less dangerous. He no longer forced people to confront the criminal justice system’s flaws: the failures of judgement that allowed it to destroy a life, and to do so less through malice than sheer incompetence. Instead of confronting a community with its failures, he became just another dangerous man, one who could be easily recognized and imprisoned. Up close, the story became safer: the system still worked. No innocent man had ever been punished. There was no reason not to trust the authorities. From a distance, however, we can see the story’s contexts and complications more clearly.

Avery, the documentary suggests, may have been targeted by local law enforcement, who both felt embarrassed by his exoneration and who were now liable to pay an impossibly high sum in damages. (Following his arrest for murder, he settled out of court for a much lower sum—money he needed urgently to fund his defense.) The series presents the argument that investigators could have planted some of the case’s physical evidence—and it makes a persuasive case. One of the key pieces of evidence against Steven Avery was a small quantity of his blood found in Teresa Halbach’s car—but a blood sample Steven gave to the police has been mysteriously unsealed, and someone appears to have drawn its contents with a syringe. The documentary doesn’t tell us what to think of this detail, or of anything else. Instead, we have the opportunity to form our own conclusions as we watch Steven’s lawyer, Jerome Buting, present his explanation: “Some officer went into that file, opened it up, took a sample of Steven Avery’s blood, and planted it.” There are other aspects of the investigation which require even less commentary, because we can see them for ourselves.

The most heartbreaking of these instances is the confession of Steven Avery’s nephew Brendan Dassey, a high school student with learning difficulties who produced, then quickly recanted, a confession that led to his uncle’s arrest. Even after he was assigned a public defender, he was questioned at length without counsel present, and left to fend for himself as investigators apparently led him toward the answers they wanted to hear, and used him to corroborate the story they thought they already knew.

In a country where we are constantly assaulted with images of police brutality, there is something newly shocking about this kind of treatment. The police don’t have to use force to convince a suspect that they will hear what they want to hear, regardless of whether it’s true. We watch as Brendan is not beaten into a confession, but apparently coerced into one by the inescapable belief that the police have all the power and he has none, and that it doesn’t matter what he says. From what the documentary has already shown us, it’s difficult to argue that he’s wrong.

“We have the evidence, Brendan,” one detective says. “We just need you to be honest with us.”

“He cut off her hair,” Brendan tries.

“What else?”

“What else was done to her head?”

“He punched her,” Brendan tries again.

“What else? It’s okay. What did he make you do?”

Eventually the detectives are out of patience. “All right,” one says. “I’m just gonna come out and ask you. Who shot her in the head?” And eventually they get the answer they want: “He did.”

But while Making a Murderer allows the viewer to believe that the authorities knowingly framed an innocent man, it also guides us towards a more likely and perhaps even more troubling verdict: that investigators may have tampered with planted evidence because they believed themselves to be serving a higher law. “I didn’t see them plant evidence with my own two eyes,” Steven’s lawyer, Dean Strang, says in Making a Murderer:

I didn’t see it. But do I understand how human beings might be tempted to plant evidence under the circumstances in which the Manitowoc County Sheriff’s Department found itself after Steven’s exoneration?...Do I have any difficulty understanding what human emotions might have driven police officers to want to augment or confirm their beliefs that he must have killed Teresa Halbach? I don’t have any difficulty understanding those human emotions at all.

This is just one of the countless examples that Making a Murderer uses to complicate the easy story the Steven Avery case has been reduced to. In Making a Murderer, we see the Avery family’s vulnerabilities exploited as the authorities seek to confuse them and turn them against each other. We can see an investigation developing not around an emerging set of questions, but around a foregone conclusion. “Before the police say they’ve opened [Teresa’s] car,” Strang argued at Steven’s trial, “before they say they know of any blood of any sort, in or on the car, before anybody even knows whether this young woman has been hurt or killed, the focus is on Steven Avery.” The politicians who assembled the Avery Task force quickly distanced themselves from him, and gave their bill a different, less tainted name. The Wisconsin Innocence Project ceased to trumpet its role in Avery’s early exoneration; his name was removed from their website. To make matters worse, once the prosecution was armed with Brendan Dassey’s confession, the district attorney Kenneth Kratz held a press conference, at which he described a possible version of events in lurid detail. After a statement like this, finding twelve jurors who would be able to go into the trial with a presumption of Steven Avery’s innocence can’t have been easy.

It’s not difficult to understand how a story that breaks a small town’s heart can deprive onlookers of the will to look at these complexities. It’s far more difficult to argue that, on a national scale, outrage can be our only response to crimes like these. If we are capable of being objective, it is our job to do so. It is our responsibility to see how often we are confronted with a complicated narrative and reduce it to a morality play, and to question the satisfaction that comes with believing that every new incarceration, no matter how needlessly punitive or unethically secured, means justice has been served. Examining a narrative like this one in all its complexity—or at least ten hours’ worth of its complexity—may give us a chance to see that even an apparently simple story is likely anything but. Someday, we may find ourselves in a position where our ability to see this complexity will allow us to act not as onlookers, but as more effective jurors.

If Making a Murderer bears a hopeful message, it’s not that the criminal justice system is doing its job; or even that we stand a chance of fixing it. Instead, it tells us that audiences have begun asking for more than the simple stories we have long been satisfied with, and that we have begun to believe that the truth may be more complicated than we have allowed ourselves to believe. Making a Murderer falls into a growing subgenre of true crime narratives that may captivate audiences precisely because they aren’t primarily concerned with captivating us at all. They don’t want to keep us snared through commercial breaks or intoxicate us with rage and pity. They have a quieter mission, but one that can have a far greater impact on their subjects’ lives. Here are the facts, they tell us. Now what will you do with them?

Watching Making a Murderer, it’s hard not to turn to Errol Morris’s groundbreaking 1988 documentary The Thin Blue Line, which is also currently streaming on Netflix. The film presents the dispassionate but ultimately devastating argument that fabricated or unreliable eyewitness accounts led to the wrongful conviction of an innocent man, Randall Adams, in the 1976 murder of a Dallas police officer. Randall Adams was exonerated in 1989, after the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals found that the case’s prosecutor, Douglas Mulder, withheld evidence suggesting that Emily Miller, the state’s key witness against Adams, had committed perjury. At the time of the Adams’s trial, The Thin Blue Line pointed out to viewers, Mulder was working to maintain a winning streak.

“People say the movie got [Adams] out of prison,” Morris recalled in a 2004 interview with the Believer, “It’s not really true. What got him out of prison was my investigation, part of which was done with a camera.” Morris allowed the viewer to take on the role of investigator, watching as witnesses unintentionally called their own reliability into question and contradicted the statements they had made at trial. The audience could compare the two competing narratives that had been presented at Adams’s trial, and make their own decisions about where the truth lay.

I thought about this authorial decision a lot when I taught college composition classes, since one of my stock assignments was Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky’s 1996 documentary Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills. Like Morris, Berlinger and Sinofsky present us with compelling evidence that the documentary’s subjects, the West Memphis Three, were innocent of the brutal triple homicide of which they were convicted in 1993. Like Morris, they too were instrumental in freeing their subjects from prison. And, like Morris, they give us the material to draw the same conclusions they have, but they do not tell us what to think. My students would watch the documentary, and return to class bearing either passionately-written indictments of the corrupt criminal justice system, or equally passionate condemnations of the evil murderers they believed the documentary had depicted. If they ended up changing their minds, their convictions would be stronger for the simple fact that they had arrived at them on their own.

This is a challenging genre of documentary—difficult to countenance as a viewer, and, I would imagine, harrowing to create—but it is one that has flourished in the last few years. Perhaps the most striking example of this recent trend is Sarah Koenig’s Serial podcast, which presented in its first season a case so hopelessly paradoxical that neither host nor listeners could decide where the truth might lie. Adnan Syed, a Maryland teenager, was convicted of the 1999 murder of his ex-girlfriend Hae Min Lee, largely because of a friend’s testimony. The story was likely enough, but many of the details of the case did not add up, even if they came tantalizingly close to doing so. Something was always missing, and throughout the series, Koenig was never able to say what that something was: only to make her listeners as fixated on its absence as she was.

Confronted with a mystery, many fans refused to move on: Serial has spawned unofficial sequel podcasts, continued media coverage, and endless conversations and debates both online and off. The story isn’t over. It never was, of course: we’ve merely developed the ability to recognize this fact. If Adnan Syed is able to appeal his conviction, some credit is due to the attention Serial brought to the case. Could Making a Murderer have a similar impact on Steven Avery and Brendan Dassey’s fates? Some of the same intense interest is already gathering around their cases on Reddit, where viewers have shared their outrage and their theories; some viewers have even used Yelp to leave Avery’s prosecutor negative reviews, and Anonymous has vowed to bring new evidence to light.

At a time when we have come to doubt the American criminal justice system’s ability not just to proceed without error but to do much of anything right, narratives like Making a Murderer and Serial provide an oddly comforting alternative to the 24-hour news cycle’s endless reiteration of thoughtless atrocities and easy conclusions. Yes, documentarians like Koenig, Morris, Berlinger and Sinofsky, and now Ricciardi and Demos tell us: Yes, the system makes mistakes. These mistakes are sometimes borne of ignorance and sometimes borne of malice, but their motivation does not change their capacity to alter a life forever, or to simply destroy it. Those who are entrusted with our protection could be the same people who harm us or our loved ones. We cannot trust that a story is true simply because we want it to be—and while it’s often impossible to know the whole truth in a criminal case, we can at least be truthful about the limits of our knowledge and the extent of our doubt. Increasingly, Americans are demanding the tools we need to do just that.