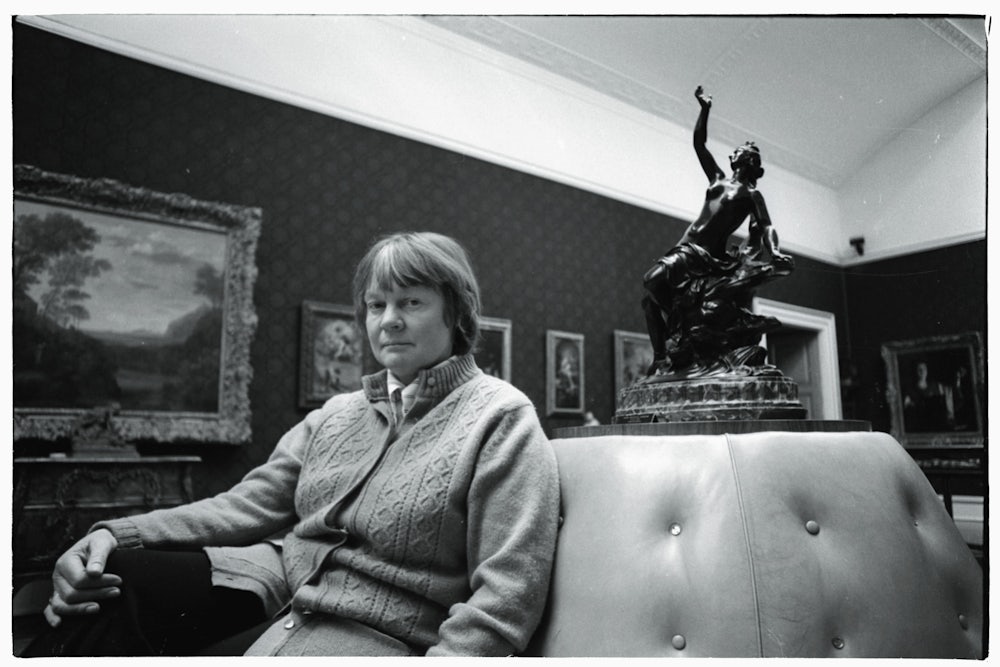

We each tend to perform different versions of ourselves in different situations: either polite or petulant with parents; less restrained around friends than around colleagues; more instinctually deferential to elders than to juniors. These are the kinds of tonal gradations letters cannot help but reveal. On the page, a letter writer—especially if she is also an accomplished author—calibrates her language precisely, aiming well-turned (or perhaps deliberately dashed-off) phrases at an audience of one. The Irish-born novelist Iris Murdoch, whose letters have been collected in Living on Paper: Letters from Iris Murdoch 1934-1995, was particularly insistent that the audience for her letters—the audience for her performance of a particular persona—should be restricted to only one person at a time. “Destroy this and all letters,” Murdoch writes at the bottom of a missive written in 1969 to an ex-student with whom she’d become “intensely, and unwisely, emotionally involved.” She adds: “And keep your mouth shut.”

Writing in 1943 to Frank Thompson, a fellow student at Oxford who had volunteered for the army and been stationed in Iraq—and was perhaps in love with her—she is casually confessional: “I should tell you that I have parted company with my virginity.” Writing to David Morgan, one of her students at the Royal College of Art, she instructs, then flirts, then chides (“I am, to be frank, a bit dismayed that you have been either unable or unwilling to get a job this summer”). To Raymond Queneau, a French writer with whom she had an emotionally charged friendship, she is agreeable, eager, and, when overeager—after, for example, a visit during which she expressed, too blatantly, her wish that their relationship might become a romantic one—apologetic (“I’m sorry about the scene on the bridge—or rather, I’m sorry in the sense that I ought either to have said nothing or to have said something sooner”).

She is occasionally repetitive in her turns of phrase (the locution “in situ” is an early favorite), and caught between a gregarious nature and a desire for solitude, as people both serious and young so often are. “One of the best things about being here,” she writes from Blackpool, on England’s northwest coast, in 1940, “is that I am quite cut off from the endless acquaintances who used to be always passing through London and calling on me. I have time to read, thank God.” She despairs, with a spontaneous passion that feels genuine rather than put-on, of her talents, her very mind: “I feel at the moment,” she writes in 1975, “that I shall never THINK again, but I daresay thoughts will return.” Presumably they did; three years later, she won the Booker Prize.

Many reviewers of the letters in Britain, where they were released several months ago, expressed unease about these multiple versions of Murdoch. Roger Lewis, writing in the London Times, suggested that the letters reveal infidelities so frequent that “had she been from the working class, instead of a fellow of an Oxford college with heaps of honorary degrees, she’d have been a candidate for compulsory sterilization.” The editors of Living on Paper treat this matter delicately in their introduction, characterizing Murdoch’s personal life as “complicated” with “each of her many correspondents unaware of…the many others to whom Murdoch also wrote.” Murdoch produced, over the course of her life, twenty-six novels, as well as several plays and numerous philosophical essays; reviewers of Living on Paper have largely seen these accomplishments as less intriguing than the fact that she also maintained a series of frequently overlapping romantic (though not always physical; as Peter Conradi notes in his biography, “Iris’s adult philosophy, both written and lived, was to give to non-sexual love an absolutely central place.”) relationships with men and women both.

In a memoir of their marriage, Murdoch’s husband of 43 years John Bayley seems almost painfully aware that the reading public was privy to his wife’s emotional and physical dalliances. “Friendship meant a great deal to her,” he writes, reasonably enough. Then, more defensively, “It was a sign of how much she valued her friends that she kept them so separate.” More than once, he emphasizes the pleasures of solitude in marriage, which is at once “a pledge of complete understanding” and “precludes nothing outside the marriage.” That this reads as a preemptive rebuttal aimed at critics of their domestic arrangement matters less than that solitude was and did—at least for them. Bayley and Murdoch married in 1956, and remained so until her death in 1999. And if Bayley at times nevertheless despaired at the affairs Murdoch allowed herself, he also refused to be defeated by them: if the woman he held tight to was sometimes someone else’s lover, she remained, ultimately, also his wife.

If Murdoch’s letters should not invite a judgment of her life, they do imply that her novels, though apparently ludicrous in their partner-swapping particulars, are not meant, at the emotional level, as comic fantasies at which the reader can comfortable chortle. Take for instance Murdoch’s 13th novel, A Fairly Honorable Defeat, which opens on a scene of wedded bourgeois bliss. Hilda and Rupert Foster are drinking “a bottle of rather dry champagne,” celebrating their twentieth wedding anniversary. They are discussing Julius King, an academic and biochemist; Julius has recently abandoned Hilda’s sister, Morgan, who had earlier abandoned her husband, Tallis, in favor of Julius. The devastated Morgan is about to visit the contented couple.

Over the course of the novel, Julius—who is, fairly explicitly, a stand-in for Satan—will deliberately and successfully break up Hilda and Rupert’s marriage by making Rupert and Morgan believe, with the aide of some pilfered love letters, that each is in love with the other. He nearly succeeds in doing the same to Rupert’s brother Simon’s relationship with his partner, Axel.

To the reader, the ways in which each character is—thanks to

self-regard and a combination of improbable but somehow convincing

coincidences—made to believe that another character, previously no more than a platonic

friend, is suddenly passionately in love with him or her, is almost wholly

ridiculous. Yet, as the letters show, these sorts of easily acquired,

passionately felt, and yet transitory romantic obsessions were hardly foreign

to Murdoch.

In a letter written in 1945, Murdoch recounts to David Hicks, an Oxford contemporary to whom she would later briefly be engaged, the details of a romantic quadrangle in which she had lately found herself involved. Murdoch had been living with Michael Foot, a man whom she did not love but “was sorry for because he was in love with me, and because he has a complex about women (because of a homosexual past) and because he was likely to be sent abroad at any moment.” A school friend, Philippa Bosanquet, came to visit. Bosanquet was then in the midst of “breaking off her relations” with Thomas Balogh, an economics professor at Balliol College, Oxford, to whom Murdoch was immediately attracted, thus involving Foot in “some rather hideous sufferings—in the course of which,” she nevertheless admits, “I somehow managed to avert my eyes and be, most of the time, insanely happy with Thomas.” Bosanquet then fell in love with Foot, whom she subsequently married (and later divorced; Murdoch and Bosanquet would go on to have a “brief physical affair,” in 1968, from which a “deep and lasting bond” of friendship would ultimately be salvaged). Meanwhile Murdoch tried to “tear” herself away from Balogh, whom she had realized “was the devil incarnate.”

The story is—not just in this retelling, but also in Murdoch’s own account—something akin to farce. And yet, knowing that she lived such destructive passion, and its failure, lends the mess of romantic relationships in her novels a kind of dignity. If comedy is tragedy plus time, then perhaps tragedy is comedy plus compassion. How foolishly we behave, Murdoch seems to say, when we believe ourselves to be in love! And yet this foolishness is no defense against—or excuse for—the actual harm that careless emotional entanglements may cause. The frantic sexual roundelay of A Fairly Honorable Defeat ends, for one character, in death.

“Seemingly no more than an account of the vicissitudes of her characters as they succumb to Julius’s stratagems,” Rubin Rabinovitz wrote in his 1970 New York Times review of that novel, “the book is also an exposition of the weaknesses in moral thought that make his victims such easy prey.” Rabinovitz does stress the “transparency” of the intrigue that sets the lovers loving, as well as the melodrama of the plot; the novel, he remarks, requires a “willing, even…unremitting suspension of disbelief.” But he also understands what is truly at stake. “As a novel of ideas,” Rabinovitz writes, “the book is an ambitious exploration of the philosophical problem of evil.”

Like many of Murdoch’s novels, A Fairly Honorable Defeat can also be read as an investigation into the limitations of self-knowledge. Lawrence Graver, writing for the New York Times, discovered an “epistemological detective novel” beneath the “domestic frenzy” of her 1973 novel, The Black Prince. “The reader,” he wrote, “is forced constantly to revise and reevaluate much of what he hears” because the characters cannot be trusted to report their actions—much less their emotions—accurately. “I acknowledge myself,” one of the characters reflects near the end of the novel, considering her behavior over the course of the preceding four hundred or so pages, “yet also I cannot recognize myself.” An individual’s own motivations, Murdoch’s novels suggest, no less than those of others, are often mysterious to him or herself.

If Murdoch’s letters show us how true this was also in her private life, her moral philosophy reveals that if true knowledge—of her self, of her lovers—eluded her, she was aware of this fact; that it was, in fact, precisely such clarity that she ultimately sought. “When I have been intimate with people,” Murdoch wrote to Brigid Brophy, a writer and political activist with whom she was romantically entangled for decades, “I have then most of all and deliciously felt their difference.” To be moral, per Murdoch, is, above all, to pay careful attention. For if one pays careful attention, one realizes “the separateness and differentness of other people…the fact…that another man has needs and wishes as demanding as one’s own.” To love someone is to come to just such a realization.

And so love presents a moral dilemma that both Murdoch and her characters wrestle with: when is loving a product of sincere attention, of careful looking, an “exercise of justice and realism” that allows the moral actor to “come to see the world as it is”—and when is it an indulgence, one more layer of the “anxious, self-preoccupied, often falsifying veil,” behind which the mind “partially conceals the world”? It is this dilemma that perhaps explains Murdoch’s ability to disdain “casual friendly liaisons,” to write that she disapproved of “promiscuity,” while maintaining multiple erotically charged relationships.

Murdoch’s letters suggest that she believed, moment to moment, that she could discern the difference between the two kinds of love in her own life. But her novels hint at an underlying anxiety. They reveal the foolishness of the man in love, how often what he imagines to be genuine passion is no more than a combination of flattery and self-regard, how easily he can be swayed by suggestion and happenstance. And so when some of this foolishness presents itself in her letters, too, the reader may be moved not to condemn, but to sympathize. Murdoch, in her fiction, is clear about the muddle that human emotions almost necessarily produce, a muddle that, at first glance, both novels and letters present as comedy. In the light of her philosophical concerns, however, her rendering—and her living—of these too human muddles become less an occasion for judgment, more purely descriptive. They become, if one pays close attention, an occasion for mercy. “The realism of a great artist,” Murdoch wrote, “is essentially both pity and justice.”

If Murdoch’s letters shock, it is because her behavior is perhaps exaggerated, but not unrecognizable. We can laugh at self-deceivers in her novels for the same reason: not because we are so constant, but because they flit from passion to passion merely more frequently than we do. If we look carefully at these contradictory, incompatible people—Murdoch’s characters; Murdoch herself—we don’t see strangers; we see ourselves.