Most people know Sisyphus, condemned by the gods to ceaselessly push a boulder up a mountain only for it to roll back down, as a symbol of utter futility. But what they often forget is that Camus, who more than any other figure popularized the myth of Sisyphus, viewed his condition as the ideal one. Stripped of all illusions, freed from hope, constantly aware of the pointlessness of his task, Sisyphus is the absurd hero, for whom “the struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart.”

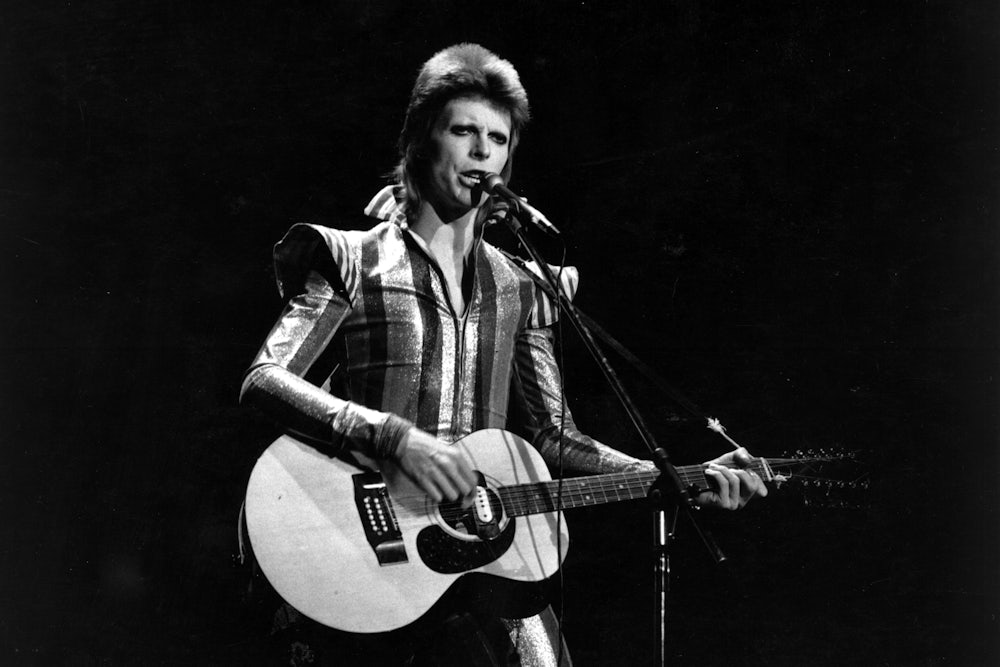

Simon Critchley’s Bowie contains an insightful chapter on “the majesty of the absurd” in Bowie’s work, which amounts to a celebration of a godless world where man can write his own fate as freely as he creates a new persona. Its essence is rebellion—against taboos, against lies, against death. It animates his last video for “Lazarus,” in which Bowie writhes on a hospital bed before slipping into a closet, back to the darkness from whence he came. This is the “staggering evidence of man’s sole dignity,” as Camus wrote: “the dogged revolt against his condition, perseverance in an effort considered sterile.”

It is not only in the face of death that our absurd condition becomes apparent. There are times when the veil of illusion lifts, our vain hopes burn away like mist in the mocking dawn of reality, and a kind of torpor settles in. But it also comes with a sense of liberation, which is one of the reasons I started work today with a smile on my face.