“Of course, you realize . . . that whoever wins this war, we shall emerge a second-rate nation.” . . . “You know, there’s only one remedy for all diseases—I mean Death.”

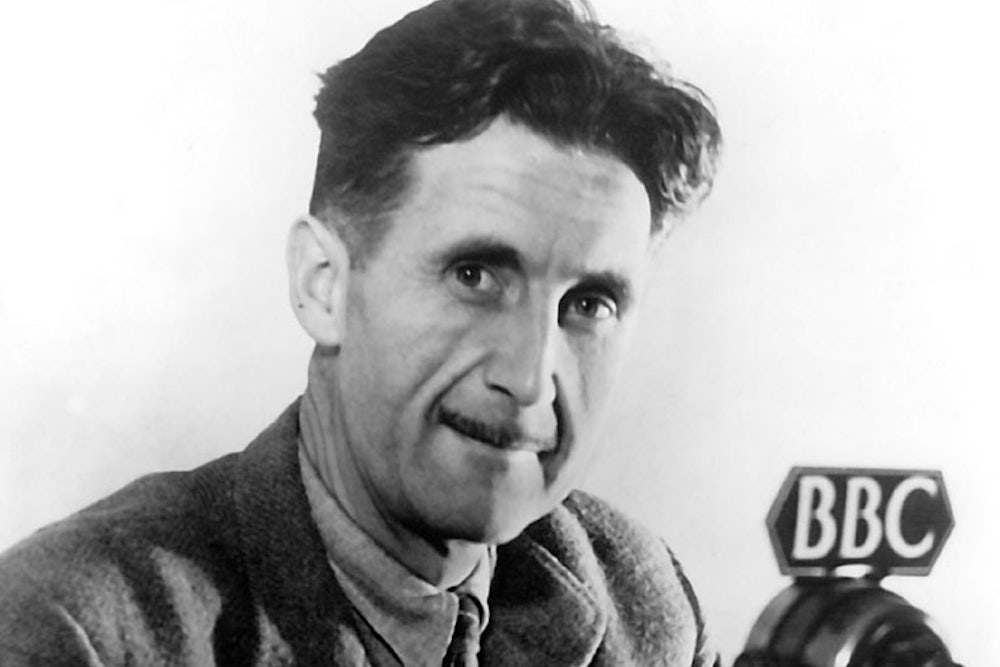

These remarks were addressed, not during World War II by one adult to another, but in 1915 to Cyril Connolly* by his twelve-year-old friend George Orwell, who died last month of tuberculosis.

Orwell’s passing has deprived the world of a man whom critics still unborn may well describe as the most important English writer to have lived his whole life during the first half of the twentieth century. Today, without fear of contradiction, we can say that England never produced a novelist more honest, more courageous, more concerned with the common man—and with common sense. Whether in fiction, autobiography, satire, pamphlets or criticism, Orwell never looked back with regret; he wrote constantly of the most urgent contemporary problems, always with the warning voice of the prophet. To literature, to the young and confused, his loss is incalculable.

In a penetrating analysis of T. S. Eliot’s “A Choice of Kipling’s Verse” (Horizon, February, 1942), Orwell observed that “Much in [Kipling’s] development is traceable to his having been born in India and having left school early. With a slightly different background he might have been a good novelist. . . .” Had Orwell himself in mind? Though this is doubtful—for less vain, less subjective a writer never lived—it’s a fact that Orwell was born in India and that at the age when Kipling was sub-editing the Lahore Civil and Military Gazette, Orwell was still at Eton, being beaten by his contemporaries for turning up late for prayers. Thirteen years later (five of them spent in the Indian Imperial Police), Orwell produced his one strictly orthodox as well as his best novel—a far more balanced picture of Anglo-Indian life than anything written by Kipling. Had the Eton “background” helped to create Burmese Days, that tragic anti-imperialist satire about a corrupt native politician’s efforts to get himself elected to the white men’s club and the helplessness of a colonial caught between his loyalty to a Burmese doctor and the pukka-sahibism of his colleagues.’

One is tempted to cry “Not bloody likely,” but it is not improbable. What is probable is that without the “background” Orwell—though he would always have been “a good novelist”—could not have acquired that rare sense of compassion, of justice, that runs through all his work. His great fortune, enhanced of course by the integrity of his character, was that while still in his twenties he had absorbed, had saturated himself in some of the extreme forms of human living in three totally different countries. What other Old Etonian has been a cop in the colonies, literally Down and Out in Paris and London, served at table, washed dishes and peeled potatoes 16 hours a day in both smart and stinking French restaurants? What son of a blimp has tramped in lice-infested rags the streets of English cities, starved, slept with thieves and beggars, and yet—neither thieving nor begging—retained his soul, his sense of humor, and written an entertaining, illuminating social document of men damned by society through no fault of their own?

Where did this ex-Kings Scholar, ex-member of the Imperial Police, ex-tramp and ex-scullion go from the flophouses of London? He went to the sprawling slums of Newcastle and Sheffield, to the unemployed mining districts of South Wales, then sat down and hammered out The Road to Wigan Pier (1937). A choice of the Left Book Club, The Road was Orwell’s first popular success. Because he never ceased to shock the middle classes, it was also his last—until the publication of Animal Farm, probably of all his works the weakest. Fearful though The Road is as an indictment of poverty and oppression, its author does not lose his sense of fair play. In an attack, not on D. H. Lawrence whom he greatly admired, but on the inverted snobbery of the proletarian intelligentsia who “sneer automatically at the Old School Tie,” Orwell can say: “Lawrence tells me that because I have been to a public school I am a eunuch.” Stating that he can “produce medical evidence to the contrary,” he adds, with typical objectivity: “If you want to make an enemy of a man, tell him that his ills are incurable.”

Unlike Lawrence (who, incidentally, died of the same illness at the same age), Orwell, however angry, seldom sneered at what he abominated, did not touch what he did not know. (To those well acquainted with huntin’-and-shootin’ England, whole sections of Lady Chatterly are utterly absurd.) Again, unlike that genius, Orwell did not travel the world in search of health and a home: He spent the best years of his life, thereby shortening it, on English soil in a ceaseless battle for Socialism—the only ism “compatible with common decency.” A man of action, he wrote out of the sheer physical experiences he had shared with the men in the mine, the slum, the suburb. A few such experiences would have caused many tougher men to lose heart. He didn’t. Only near the end, in the superstate nightmare of Nineteen Eighty-Four, did Orwell, already mortally ill, cast aside his humor.

His most humorous book, in fact, a work as steeped in middle-class English life as any early novel by Wells (by whom he was obviously influenced), was written during those awful months leading up to “Munich,” after Orwell had been seriously wounded fighting Fascism in Spain. Coming Up for Air (now published in the U.S. for the first time) is a masterpiece of characterization, an astonishing tour de force. “Do you know the active, hearty kind of fat man,” asks George Bowling, the narrator, “that’s nicknamed Fatty or Tubby and is always the life and soul of the party? I’m that type. ... A chap like me is incapable of looking like a gentleman.” Now how is it possible for a middle-aged suburban insurance agent thus to describe himself? How, moreover, could such a man write a book about his life, his innermost thoughts, and get away with it? It is possible only because Bowling of Lower Binfield had Orwell’s honesty, because the India-born Old Etonian had the Bowlings of Britain nearest his heart, every nuance of their speech on the tip of his tongue. Though deadly serious—a novel that, on the eve of World War II, expressed the almost inexpressible fears of every Englishman, warning them in frightening detail of the coming catastrophe—Coming Up has a guffaw on every page. It is probably the only book in which Orwell returned to the past. By so doing, he painted a picture of middle-class England from 1893 to 1933. Through this one man’s memories and a return to the scenes of his childhood, Orwell shows how the Bowlings of the villages near London were sucked inexorably into the city, how the country was swallowed up by factories, how the pubs gave way to fancy tea shoppes, the dignified hotels to pewter and chromium, and the deep pond in which young George used to fish for carp to a vast dump for cans.

Disgusted, the middle-aged Bowling turns his back on the ruined land:

I’ll tell you [he says] what my stay in Lower Binfield taught me. . . . It’s all going to happen. All the things you’ve got at the back of your mind, the things you’re terrified of... the bombs, the food queues, the rubber truncheons, the barbed wire, the coloured shirts, the slogans, the enormous faces, the machine-guns squirting out of bed-room windows. It’s all going to happen.

Well, we know what happened. We know that the boy who predicted that Britain would “emerge a second-rate nation” from World War I was one of the millions who helped prevent those guns from squirting out of English windows in World War II. Does this make him, as some critics have inferred, a false prophet, a man who, because he was born in India and educated at Eton, didn’t know that those incapable of looking like gentlemen are as capable as any gent of behaving like heroes? It is more likely that Orwell, just because he knew and loved the Bowlings so well, loathed and feared “the streamlined men” so much, felt no cry of warning could be uttered too loud.

*Enemies of Promise, Revised Edition (Macmillan, 1948)

With the exception of The Road to Wigan Pier (not published in the U.S.) all the books by Orwell mentioned in this review are published by Harcourt, Brace.