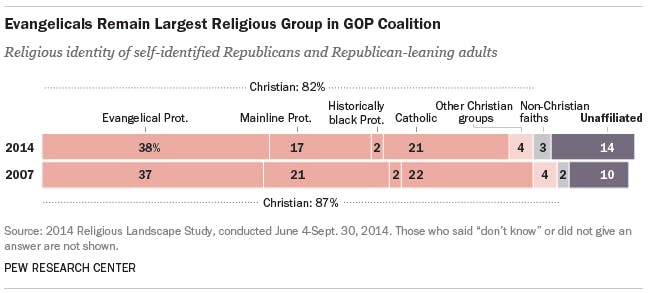

White Evangelicals are doing well. While white Catholics and mainline Protestants have shed membership over the last decade, ostensibly losing ranks to the growing number of unaffiliated and non-religious, Evangelicals have held steady. The persistence of Evangelical numbers has coincided with a consolidation of Evangelical political consensus: As of 2014, Pew found that the share of Evangelicals identifying as Republican or Republican-leaning has never been higher, at 68 percent. In fact, Evangelicals comprise the single largest religious constituency inside the GOP, making up 38 percent of Republicans, with Catholics trailing them at 21 percent.

In short, thanks to their numbers and their historical role as members of the GOP coalition, the Evangelical vote has perhaps never been more important for any given Republican hopeful, despite the overall trend in America toward secularization.

And this year they’re polling for Trump.

A recent NBC/Survey Monkey poll found white Evangelical support for Trump at 37 percent, significantly more than the 20 percent captured by his closest competitor, Ted Cruz. Meanwhile, the PRRI recently found that white Evangelicals have been steadily warming up to Trump, with 53 percent expressing a favorable view of the candidate, up from 37 percent in November 2015. While Cruz and Marco Rubio, each potential Evangelical-friendly alternatives to Trump, have also appreciated in esteem among Evangelicals since last year, Trump still leads them both in the “very favorable” category, with 19 percent of Evangelicals viewing the Donald very favorably, compared with Cruz at 15 percent and Rubio at 8 percent.

How could this happen? A flurry of articles have sought to unravel the mystery of Trump’s appeal to religious voters so unlike himself. How can a leering, thrice-divorced business mogul who profits off strip clubs and has appeared on the cover of Playboy capture the allegiance of voters who self-identify as thoroughly Christian?

At The New York Times, Russell Moore, president of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention, suggested Evangelicals who are drawn to Trump have been seduced by “the other side of the culture war, that image and celebrity and money and power and social Darwinist ‘winning’ trump the conservation of moral principles and a just society.” At ThinkProgress, Jack Jenkins proposed that Evangelical Trump fans are simply not all that religious, attending church rarely. And at The Atlantic, Jonathan Merritt argued that Trump’s bombast and pugnaciousness speak to “growing anti-establishment sentiments held by many evangelical Christians.” Others have argued that Trump’s promises excite a base convinced of American decline, and all of these reasons are likely pieces of the overall mosaic of Evangelical Trump support.

There may be another piece yet, best summed up with a hoary old standard of leftward provenance: It’s the economy, stupid. “I think one of the things [Trump] does do, which is intriguing to a lot of blue collar Evangelicals, is pull away the curtain on what’s going on with the economy,” Lydia Bean, author of The Politics of Evangelical Identity, told the New Republic. “And I think that’s been missing from Evangelical discourse: real power, what’s going on in the economy. And just an answer is intriguing, it makes people feel powerful. He says: I’m on your side, here’s what’s going on, there are all these stupid elites in the politics sphere kowtowing to business elites because they need their money, but I have my own money, so I’m going to tell it like it is.”

Economic decline is a serious concern among GOP primary voters. A recent Bloomberg poll found that only 11 percent of likely Republican primary voters strongly agreed the American Dream is “alive and well,” and only 26 percent strongly agreed that people like them can still get ahead. Meanwhile, a mere 13 percent strongly agreed they’re better off now than they were four years ago, and only 16 percent strongly agreed that they will be better off four years from now. Sixty-three percent were in favor of stopping any new free trade agreements in order to keep jobs in the U.S., while 72 percent favored building a wall along the nation’s southern border to keep immigrants out.

Another interesting feature of the Bloomberg poll: Only 18 percent of Trump supporters claimed their interest in the candidate arises from having the same worldview. On the other hand, 66 percent said their support is thanks to Trump’s willingness to tell “the truths other people won’t say,” and 37 percent premised their appreciation on the tycoon’s business record.

Historically, “[Evangelicals] have been told by their leadership that the problem is liberals,” Bean said, “their culturally liberal ways, their cultural Marxism, whatever you want to call it. And this liberal elite is overpowering our Christian values. The majority of Americans are with us, but the liberals are controlling the schools and controlling the government.” But Bean pointed out that narrative is beginning to weaken. “I think that’s starting to lose its compelling-ness: In same-sex marriage, for example, opinion polls show that the majority of Americans don’t care or are okay with same-sex marriage.”

What’s been missing from the Christian right is a narrative about the economy. While business leaders used to be highly respected in Evangelical culture “because they’re self-disciplined, and the hand of the market is the hand of God,” Bean noted, that story neglected to provide an explanation of how material power works in society. “There hasn’t really been an account in the Christian right about the economic power that governs society, influences culture. So there’s the business elite, the banking elite, and I think that’s becoming a part of the Christian right narrative.”

Trump is more than willing to point out how business leaders are manipulating politicians and selling out average Americans. “I was saying make America great again,” Trump said this January to a crowd of students at Evangelical Liberty University, “and I actually think we can say now, and I really believe this, we’re gonna get things coming ... we’re gonna get Apple to start building their damn computers and things in this country, instead of in other countries.” Trump went after Nabisco and Ford in the same speech, lamenting, “We’re losing our jobs, we’re losing our manufacturing jobs,” to applause, cheers, and laughter.

But supposing Evangelicals are attracted to Trump’s explanation of economic decline and his independence from moneyed interests, why haven’t Evangelical leaders like Moore been able to rein in their support with reminders of his flagrant disrespect for Christian morality? After all, if, as Bean says, an economic narrative is a relatively new development on the Christian right, why would they so suddenly abandon a longstanding and fervid interest in morality in politics to latch onto it?

“This is where the Christian right leaders made their bed and now they have to lie in it,” Bean said. “They didn’t really ever do a good job in insisting on any distinctive Christian character in their leaders. They were usually determined to be good partners in the Republican coalition, which meant they would endorse anyone who was a strong Republican, and they would play along. It started with Reagan: Reagan is a Godly man over Jimmy Carter. But I don’t know of any way Reagan out-Christianed Jimmy Carter. And this continued on, getting increasingly implausible, concluding with Mitt Romney. Historically Southern Baptists have taught that the LDS Church is a cult, but with Romney, they were willing to basically scrub teaching to endorse Romney. So the Billy Graham Association pulled down their website during the 2012 campaign season, scrubbed all the anti-Mormon material off the website, and put it up again with an endorsement for Romney. And once you’ve done that, you’ve sort of just cut the nerve.”

With that nerve severed, Evangelical voters are free to gravitate to whichever candidate is providing the most cogent reflection of their anxieties, and Trump, with his vivid account of the fall of the white American middle class, appears to be that candidate. Evangelical leaders may balk at his boorish amorality, but others have gone along with the Trump momentum: Just this week, Jerry Falwell Jr., the son of famed televangelist Jerry Falwell, endorsed Trump for president. And if he hadn’t, Bean said, it wouldn’t really have mattered: “The base is driving this, they like Trump. Ever since the rise of Fox News, the right has their own way of communicating directly to Evangelical voters that doesn’t go through Christian organizations. ... And the Christian right leaders are suddenly watching, helpless. So they’re making the best of a bad situation, pretending they have control, but they don’t.”