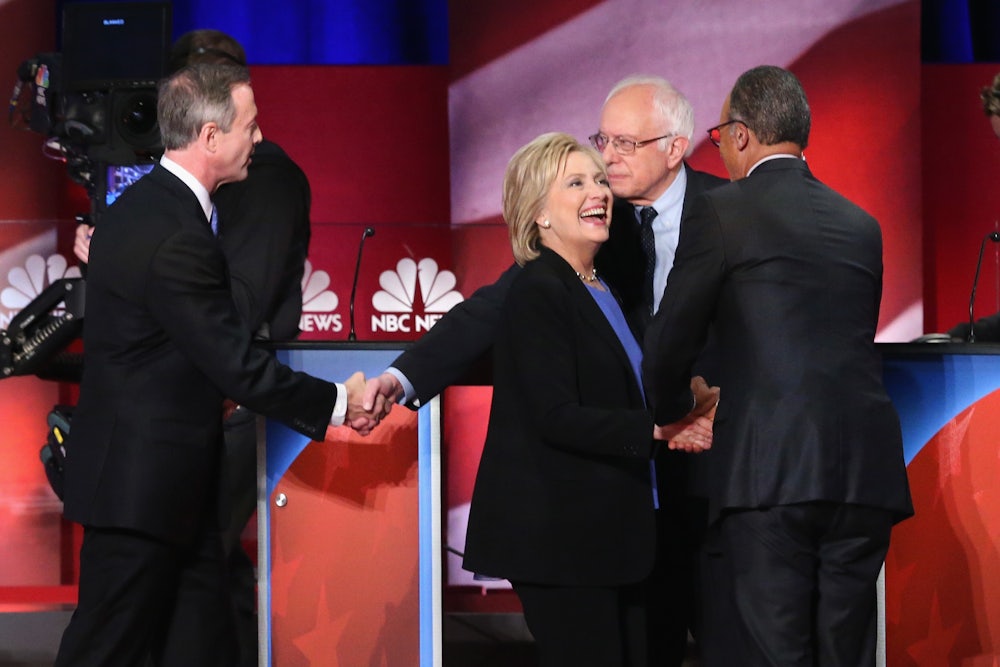

The Democratic presidential campaigns have spent much of the last year meticulously strategizing and organizing for a single night in Iowa that lends itself to spontaneity and surprise. But thanks to the arcane—or, if you prefer, just plain wacky—rules that govern the state’s Democratic caucuses, Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders, and Martin O’Malley and their strategic geniuses can exert only so much control over what happens inside the 1,681 caucuses across the state. The tightness of the Sanders-Clinton race will lend itself to a night of favor-swapping, neighborly bickering, and general chaos—with O’Malley’s supporters at the center of the storm.

With the race too close to call—over the weekend, the Des Moines Register/Bloomberg polling average gave Clinton a narrow 45-42 percent edge over Sanders, with O’Malley lagging at 3 percent—the big question has been about turnout: Will Sanders’s younger, less-experienced supporters show up? But there’s another wild card on Monday night that’s even harder to predict—and a lot more fun to ponder: how O’Malley supporters could tip the race to either of the frontrunners.

This delicious possibility stems from the arcane rules of the Democratic caucuses. While the Republican caucuses are relatively straightforward—secret-ballot votes for candidates—the Democratic caucuses are a whole unique brand of democratic experiment. Everyone’s preference is public, as supporters stand in their candidate’s corner of the room to be counted. The winner is ultimately determined by delegate counts based on percentages the candidates accrue. If a candidate doesn’t end up with at least 15 percent at the end of two rounds of tallying, then she or he is considered “nonviable” in the precinct—and earns no delegates unless others come along. The Democrats then have a 30-minute re-alignment period, where they can move to another candidate or choose to be “uncommitted.”

That’s why O’Malley’s supporters will be so coveted: If he doesn’t tally 15 percent in a precinct, his supporters can join another campaign. Or, if they’re close to being viable, they can try to pick off a few Sanders or Clinton supporters, or undecideds, to join them. “You have to think in a year like this year, someone who shows up to the caucus and doesn’t have a candidate picked out, they’re likely a typical caucus-goer, a Democratic who’s done this before, and Clinton’s or Sanders’s message is not resonating,” says Keith Geiken, a consultant who’s trained the Sanders and O’Malley campaigns on caucus procedures.

Nancy Bobo, an O’Malley precinct chair in Des Moines, says she plans to target the Sanders crowd, where she sees “wiggle room” if O’Malley is near 15 percent. “I think among his supporters there’s some question whether he can be elected,” she said.

But that will only happen in the precincts where O’Malley has significant support. In many more Iowa precincts on Monday night, O’Malley will come up short. What happens then is anybody’s guess.

In 2008, the last time Iowa had a contested Democratic caucus—and one that featured eight candidates—the evening was a case study in the kind of unpredictability that can ensue. In Audubon County, Clinton volunteer Pat Rynard expected his candidate to win the precinct, based on the campaign’s organizing numbers. Rynard, who now runs an Iowa politics blog, still bitterly laments this “one idiot” in former New Mexico Governor Bill Richardson’s group who changed his mind and was persuaded to join John Edwards’s corner. Richardson had only been viable by a single person in the precinct, so the defection left the rest of his supporters free to realign with a new candidate. Angry that their former caucus-mate had betrayed him for Edwards, the others all went over to Obama for revenge, Rynard says. That helped contribute to Obama’s narrow win over Clinton in Audubon County, 35 percent to 33 percent, adding to the pile of delegates that propelled him to an upset win in Iowa.

Occasionally, the supporters of a nonviable candidate already know where they’ll go. On 2008 caucus night, another Clinton precinct chair, Claire Celsi of West Des Moines, recalls watching every one of Dennis Kucinich’s supporters walk over to the John Edwards corner during the 30-minute re-alignment period without saying a word to anyone else. “You can tell they had a plan.” They did: The Edwards and Kucinich campaigns had struck a deal beforehand.

O’Malley’s campaign says there’s no similar deal in the works to send his backers into Clinton or Sanders camps. On Monday night, O’Malley delegates will apparently be free to persuade—or be persuaded. And that’s where the fun, and chaos, will begin.

If the winner on Monday is determined by the strongest turnout operation, then Clinton likely has the edge. Remembering her 2008 loss, blamed in part on Obama’s superior ground game, Clinton’s campaign has built a far more extensive one this time around much earlier in the campaign season. This fall, the Clinton campaign began holding in-person trainings for precinct volunteers complete with mock caucuses, role-playing, and quizzes to prepare for caucus-night persuasion. The Sanders campaign has had to play catch-up to match Clinton’s operation, bulking up its Iowa organization rapidly in December and January—but has made significant strides, opening nearly as many field offices as Clinton’s 26.

But if Sanders supporters show up and keep the margin razor-thin on Monday night, it could be O’Malley backers who determine the winner—precinct by precinct, and sometimes caucus-goer by caucus-goer. The persuasive techniques used in these situations don’t always come from the campaign script, or the themes that have been drilled into volunteers at training sessions. In 2008, Sara Riley—who’s an O’Malley precinct chair this year, in a county in Cedar Rapids—was backing then-Senator Joe Biden. She successfully swayed a pro-LGBT rights supporter of low-polling Senator Christopher Dodd to join Team Biden using tactics that embarrass her a bit in retrospect. “I kind of maybe exaggerated how good Biden was on LGBT” issues, Riley recalls now. “I had no idea if that was true, but it felt like the right thing to say.” Riley says she rested more easily after the caucus when she found out her pandering was “probably” pretty accurate. This year, she says, even if she has to “go and cry and make a scene,” O’Malley will be viable in her precinct, Riley swears.

The O’Malley supporters I spoke to didn’t want to talk about what they’d do if their efforts can’t make their man viable. But in most precincts, of course, it’ll certainly be Sanders and Clinton supporters who are trying to win them over. Except, in the Iowa Democratic caucuses, it’s not even that simple: If the delegate count in a precinct is close between Sanders and Clinton, one of the campaigns may send some of its own supporters to the O’Malley corner, to prevent the other frontrunner from winning the delegates. The Clinton campaign even has an app for volunteers to count the number of supporters for each candidate at the precinct, and send caucusers to O’Malley’s side to make him viable and keep them from shifting to Sanders.

Recently on Reddit, Sanders supporters have been recommending their Iowa peers use the same tactic to foil Clinton’s delegate counts. But overall, the Sanders campaign has been less focused on such advanced maneuvers and more on simply getting voters and volunteers to show up for their first caucus. But some Sanders backers, like Susan Nelson, a precinct chair in rural, eastern Floyd County, are old hands. Nelson expects that her O’Malley neighbors will want to hear about Sanders’s plan to expand Social Security and his environmental record opposing fracking, including the natural gas Bakken pipeline proposed to run across the state. “I was just talking to someone this morning about electability,” she told me on Friday. “He can win on issues, things like expanding Social Security. There are people in town trying to make it on Social Security.”

Mostly, Nelson says she’ll advise her fellow Sanders backers to tailor their messages to the person they’re trying to sway. In 2008, Nelson was backing Joe Biden, who was one person short of viability in the precinct. She says she convinced the lone Chris Dodd supporter—the local fire chief, who supported Dodd because of a firefighters union endorsement—to switch by selling him on her research beforehand of Biden’s strong record on labor rights. Nelson says she learned another lesson from that caucus: Setting the right mood in the room matters. “This year I’m bringing chocolate chip cookies” to soothe cranky voters, she said.

Celsi, Clinton’s West Des Moines precinct chair, also stresses keeping the mood positive and friendly—and refraining from shouting matches. She says policy will matter: The key to bringing O’Malley supporters to Clinton’s side, she says, will be making the case that their candidate is closer to Clinton than Sanders on hot-button issues. “For example,” she says, “I think O’Malley and Clinton have more in common on gun control than Bernie and O’Malley do.” The other selling point, she says, will be more pragmatic: echoing the case that Clinton has made throughout the campaign that she’s more viable than Sanders against a Republican next November.

O’Malley has been urging his supporters to avoid such enticements. The primary message in O’Malley’s volunteer training sessions these last two weeks, says his deputy Iowa director Kristin Sosanie, has been to “hold strong.” But the campaign—like Sanders’s and Clinton’s—can only do so much to guide its supporters and plan for every strange scenario on Monday night. The three campaigns may have mapped out voters’ preferences and every possible outcome down to a science, but they can’t account for the human element of a Democratic caucus night.