I have remarked before on the mystifying ability of great playwrights to predict human actions and calamitous events. One example I recently noted is the similarity between the way Shakespeare’s Cleopatra abuses a messenger who brings her bad news and the Bush administration’s discrediting of people such as Joseph Wilson and Richard Clarke when their messages diverge from official Iraq policy (a process I call “maiming the messenger”). Another example of prophetic Shakespeare can be found in these lines from Sonnet 64, curiously resonant of the recent catastrophe in Southeast Asia:

When I have seen the hungry ocean gain

Advantage on the kingdom of the shore,

And the firm soil win of the watery main,

Increasing store with loss, and loss with store;

When I have seen such interchange of state,

Or state itself confounded to decay,

Ruin hath taught me thus to ruminate—

That Time will come and take my love away.

This thought is as a death, which cannot choose

But weep to have that which it fears to lose.

How could Shakespeare, who lived near the North Sea, have imagined what sounds very much like the recent tsunami in the Indian Ocean, with its devastating floods and tidal waves, and its confounding impact on people and property?

To take another example: the ongoing flap over the adversarial style and controversial actions of Lawrence Summers has a theatrical precedent in Euripides’s Bacchae. King Pentheus rudely spurns an ecstatic new religion, headed by Dionysus, which even his own mother has embraced. As a result of Pentheus’s stubborn resistance, he is torn to pieces by maenads. His mother, Agave, gets to brandish his severed head, while Dionysus threatens all blasphemers with a similar fate.

The maenads of political correctness at Harvard (a group that includes a number of male professors) have visited a milder form of Pentheus’s doom on Summers for some blasphemous remarks he made at a National Bureau of Economic Research conference in January about whether women share men’s aptitude for mathematics and the physical sciences. Summers’s speculations on the subject, however tentative, were no doubt misguided, as he himself has duly admitted. They were a mistake of judgment; but they are being treated as an impermissible deviation from one of the central precepts of current campus dogma, which is that generalizations about sexual or racial characteristics are strictly forbidden--unless, of course, they apply to white males.

Ibsen also wrote a prophetic play about a man whose opinions affront received opinion, and who suffers retaliatory action as a result. An Enemy of the People concerns a doctor who discovers that the supposedly therapeutic springs on which a town depends for its prosperity are actually contaminated. Instead of the gratitude he expects for saving tourists from a lethal version of Montezuma’s revenge, he is excoriated, pilloried, and exiled for threatening the livelihood of the town.

Admittedly, the Harvard-Ibsen parallel is hardly exact. Summers has made no beneficial discoveries regarding the water supply in Eliot House, though his improvements at Harvard have been substantial (the university’s generous loans to poorer students, its expansion into Allston, even some belated efforts to increase the number of female professors). But many professors are treating Summers in the way the town treated Doctor Stockmann, as an enemy of the people who deserves no better than to be expelled willy-nilly from the community.

It is a commonplace that free expression is not highly valued in the academy these days. But it is unusual to find a faculty trying to impose speech codes on the office of the president instead of the other way around. (Another Harvard innovation!) Previously, Summers ruffled faculty feathers by openly opposing as anti-Semitic demands that Harvard divest from Israel and by suggesting that an African American professor, Cornel West, should consider improving his scholarship. Many have complained about his hectoring manner and “intimidating” style (though one faculty member wondered how tenured Harvard professors could ever feel truly threatened).

But as the February 22 faculty meeting made abundantly clear, the real issue here is one of power. A contentious, scrappy, and sometimes unmannerly administrator, Summers has been making decisions and exercising privileges that Harvard professors believe traditionally belong to them alone. And while a few university women have been understandably upset by speculations they consider unsupported and insulting, other faculty have seized on this event as a pretext to pluck his presidential feathers. At its March 15 meeting, the faculty passed one resolution of no confidence in the president, and another expressing regrets about his remarks. The seriously wounded Summers may not last another term. Faced with similar public humiliation from his antagonists, the proud Coriolanus replied, “I banish you!” Ah, the days of classical glory. Summers, more conciliatory, has abjectly apologized to the faculty and promised to change his ways. Whether he stays or goes, his office has been seriously compromised, if not emasculated.

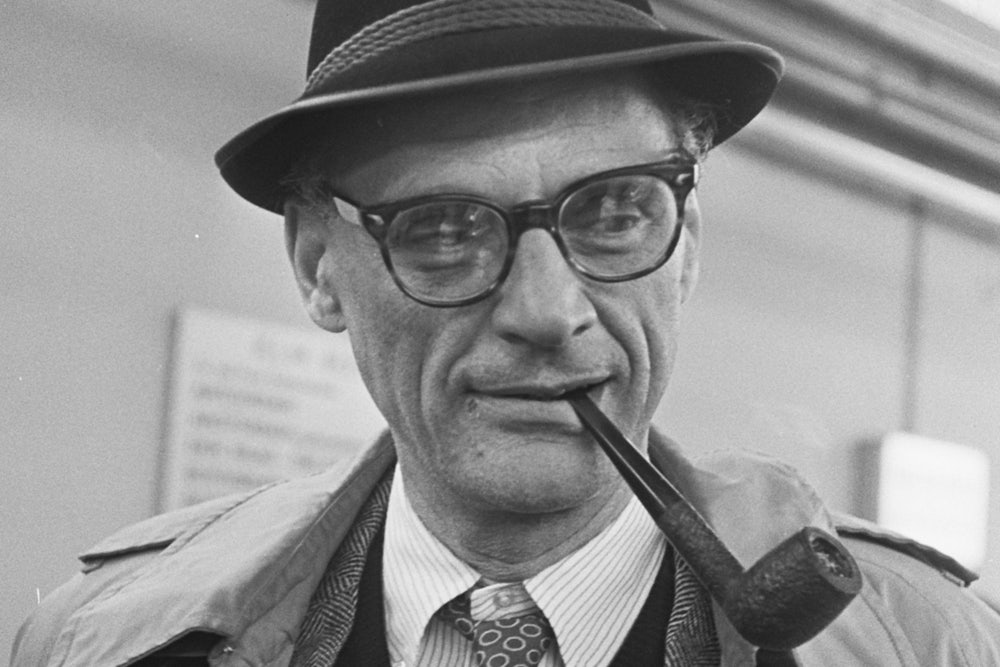

An Enemy of the People happened to have been Arthur Miller’s single attempt at theatrical adaptation, no doubt for reasons of a similar nature. His recent death reminds us that he, too, was once a victim of political hysteria--that 1950s form of jihad known as McCarthyism. Hauled before a congressional committee investigating communist infiltration into the entertainment industry, Miller refused to name names, though he was never a party member himself. The committee chairman offered to waive prosecution if Miller would persuade his wife, Marilyn Monroe, to be photographed with him. Miller refused and was thereupon convicted of contempt of Congress (a conviction that was later overturned).

Miller wrote The Crucible as a commentary on this experience, using the Salem witch trials as a metaphor for the proceedings of the House Un-American Activities Committee. As Robert Warshow and others observed at the time, the analogy was faulty. The witches of Salem were a figment of the diseased Puritan imagination, while American communists were a reality, though one admittedly exaggerated by the feverish right-wing mind. But like Miller’s behavior before the committee, the play was a noble act of conscience, as well as an implicit indictment of all those (including Elia Kazan, his former friend and director) who had informed on others in order to save their own professional skins.

The Crucible was not a prophetic play so much as a disguised evocation of an existing event. There is a difference (as M. H. Abrams noted in The Mirror and the Lamp) between visionary artists who light up new pathways and analytical artists who reflect an existing reality. Arthur Miller was surely among the latter species. Although not a prophetic playwright, he offers a powerful example of the playwright as witness, particularly to the Great Depression that generated much of his art. All My Sons indicted profiteering war contractors. Death of a Salesman criticized a society that discarded working people “like an old shoe” after they had ceased to be useful. A View From the Bridge, as well as being another attack on political informers, was a study of illegal immigration. The American Clock followed the downward spiral of a middle-class family after the stock market crash.

These plays, and most of his plays that followed, were powered by the indignant energies of a previous age. One of the few clear voices of the theatrical left, Miller never got hoarse battling injustice, inequality, and hypocrisy. But he lacked any formal ideology through which to confront these wrongs, and so he tended to duck the issue of social or political responsibility. It is significant that one of Miller’s most oft-quoted lines--”Attention must be paid”--does not have a subject. Who should pay attention? Me, you, the president of the United States, Yogi Bear? One of my continuing objections to Miller’s work was that it constituted the Theater of Guilt, a form that leaves the audience wallowing in self-recrimination, paying off its conscience by throwing a handful of change at the homeless.

Whatever the reason, Miller eventually began to lose his credibility with the majority of American critics, though his name continued to be inseparable from twentieth-century American drama. Miller often expressed regret over the way his own country had ignored or rejected his later work, the numerous awards and tributes bestowed on the earlier plays notwithstanding. “When I looked back,” he wrote in his painfully honest memoir Timebends, “it was obvious that aside from Death of a Salesman every one of my plays had originally met with a majority of bad, indifferent, or sneering notices.…I exist as a playwright without a major reviewer in my corner.… Only abroad and in some American places outside New York has criticism embraced my plays.”

Up until the powerful Broadway revival of Death of a Salesman by the Goodman Theatre in 1999, that statement had been regrettably true. While his later plays were regularly dismissed by the major media critics, who generally prefer writers they have discovered themselves, the name of Arthur Miller remained a talisman in Great Britain. Bernard Shaw once remarked that England and America are two nations divided by a common tongue. It seemed more accurate to say that we were two nations divided by a common playwright.

I should confess that up until this mainstream backlash I was among those miscreants who failed to stand in Arthur Miller’s corner. As a minority reviewer for the New Republic, a magazine with virtually no impact on the box office, I saw no reason to pull my punches regarding such inflated Miller ideas as “the common man as tragic hero,” especially when it led to the popular conviction that there was an unbroken line between Agamemnon in his chariot and Willy Loman in his Chevy. (One popular theater anthology was called From Aeschylus to Arthur Miller.) To me, the line was clearer between Death of a Salesman and Yiddish family drama as drawn through the plays of Clifford Odets. As the Goodman Theatre revival of Death of a Salesman made clear, the overwhelming power of Miller’s masterpiece was a result of his uncanny understanding not of tragic theory but of family dynamics.

Yet when the majority reviewers also began to turn on Miller, as well as on Tennessee Williams and Edward Albee, I was appalled, and not a little contrite. It was one thing for a few of us fringe apostates to nip at the heels of the great. But if our three major playwrights couldn’t receive the respect they deserved from mainstream American reviewers, then there was something a little rotten in the state of criticism, and I felt an obligation to defend them. This may sound like sheer perversity, or some crazy form of territoriality. But it was a lesson that Miller already knew in his bones--that there were only two saleable stories for the mainstream press, success and failure. Or, to paraphrase an ancient Greek maxim, those whom the media would destroy, they first make famous.

I am relieved that, before his death at the age of eighty-nine, Miller was able to regain his place at the height of his profession. I am also relieved that I had the opportunity to recant some of my harsher criticisms, most publicly in an introduction I made to his Massey Lecture at Harvard in 1999. I still have problems with Miller’s often ungainly prose style, but then O’Neill was no Demosthenes either. And if Miller had the polemicist’s weakness for similes rather than the poet’s capacity for metaphors, it is impossible not to respect his consuming dramatic power, as well as his profound influence on later American dramatists, notably David Mamet (who also explored the jungle habitat of the salesman), Tony Kushner (who studied the virulent effects of red-baiting, particularly on Ethel Rosenberg), and Donald Margulies (who paid tribute to Miller’s family conflicts and urban themes in The Loman Family Picnic and his current production, Brooklyn Boy).

A public intellectual as well as a private artist, Arthur Miller played a pivotal role in most of the cultural and political dramas of our time. Particularly in his role as a president of PEN, he forcefully represented the interests of persecuted literary people throughout the world. He was American theater’s elder statesman, who best embodied our dramatic image both at home and abroad. His death leaves yet another vacant lot in a once beloved and familiar neighborhood.