Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon was published in 1977 to unreserved praise; American readers had found a new voice. The plot of the novel, a young man’s search for a nourishing folk tradition, was familiar from other AfroAmerican books, but Morrison’s fireside manner—composed yet simple, commanding yet intimate—gives the novel a Latin American enchantment. Reading backward through Sula (1973) to Morrison’s first novel, The Bluest Eye (1969), one sees her trying out different versions of what she calls her “address,” rehearsing on more modest subjects the tone and timbre that give original expression to the large cultural materials in Song of Solomon.

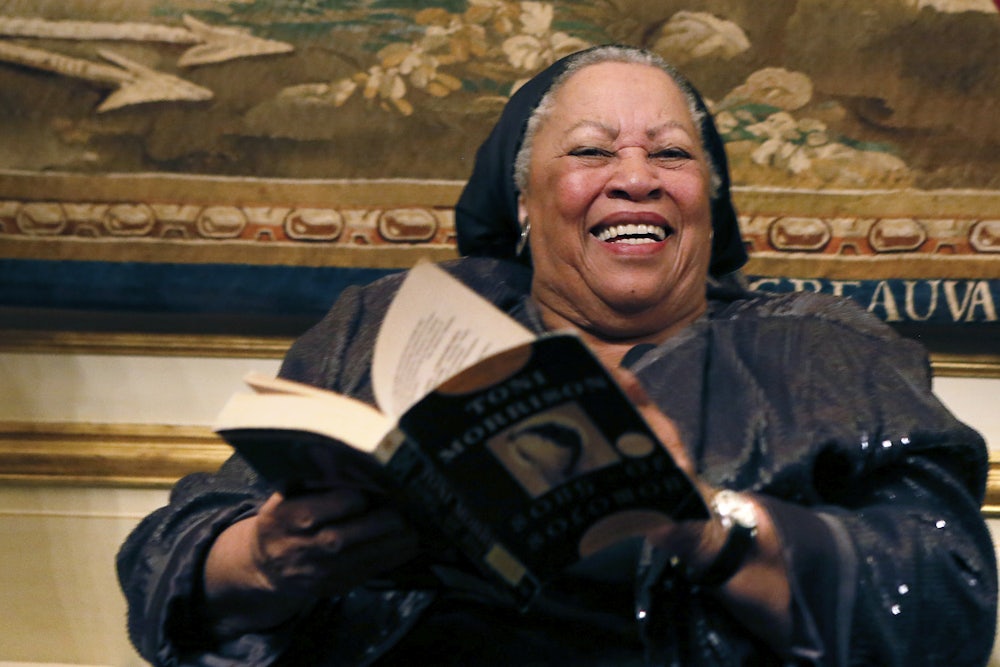

How and why she arrived at that special voice were the questions that brought me to Toni Morrison’s busy office at Random House (where she is an editor) just after she finished Tar Baby. Although our interview was interrupted several times, when Toni Morrison started talking about writing she achieved remarkable concentration and intensity. This—not editorial business or author small talk—was clearly where she lived. No matter what she discussed—her loyalty to the common reader, her eccentric characters, her interest in folklore—her love of language was the subtext and constant lesson of her manner. She performs words. Gertrude Stein said poetry was “caressing nouns.” Toni Morrison doesn’t like to be called a poetic writer, but it is her almost physical relation to language that allows her to tell the old stories she feels are best.

Thomas LeClair: You have said you would write even if there were no publishers. Would you explain what the process of writing means to you?

Toni Morrison: After my first novel, The Bluest Eye, writing became a way to be coherent in the world. It became necessary and possible for me to sort out the past, and the selection process, being disciplined and guided, was genuine thinking as opposed to simple response or problem-solving. Writing was the only work I did that was for myself and by myself. In the process, one exercises sovereignty in a special way. All sensibilities are engaged, sometimes simultaneously, sometimes sequentially. While I’m writing, all of my experience is vital and useful and possibly important. It may not appear in the work, but it is valuable. Writing gives me what I think dancers have on stage in their relation to gravity and space and time. It is energetic and balanced, fluid and in repose. And there is always the possibility of growth; I could never hit the highest note so I’d never have to stop. Writing has for me everything that good work ought to have, all the criteria. 1 love even the drudgery, the revision, the proofreading. So even if publishing did grind to a halt, I would continue to write.

LeClair: Do you understand the process more and more with each novel that you write?

Morrison: At first I wrote out of a very special place in me, although I did not understand what that place was or how to get to it deliberately. I didn’t trust the writing that came from there. It did not seem writerly enough. Sometimes what 1 wrote from that place remained sound, even after enormous revision, but I would regard it as a fluke. Then I learned to trust that part, learned to rely on that part, and I learned how to get there faster than I had before. That is, now I don’t have to write 35 pages of throat-clearing in order to be where I wish to be. I don’t mean that I’m an inspired writer. I don’t wait to be struck by lightning and don’t need certain slants of light in order to write, but now after my fourth book I can recognize the presence of a real idea and I can recognize the proper mode of its expression. I must confess, though, that I sometimes lose interest in the characters and get much more interested in the trees and animals. I think I exercise tremendous restraint in this, but my editor says “Would you stop this beauty business.” And I say “Wait, wait until I tell you about these ants.”

LeClair: How do you conceive of your function as a writer?

Morrison: I write what I have recently begun to call village literature, fiction that is realty for the village, for the tribe. Peasant literature for my people, which is necessary and legitimate but which also allows me to get in touch with all sorts of people. I think long and carefully about what my novels ought to do. They should clarify the roles that have become obscured; they ought to identify those things in the past that are useful and those things that are not; and they ought to give nourishment. I agree with John Berger that peasants don’t write novels because they don’t need them. They have a portrait of themselves from gossip, tales, music, and some celebrations. That is enough. The middle class at the beginning of the industrial revolution needed a portrait of itself because the old portrait didn’t work for this new class. Their roles were different; their lives in the city were new. The novel served this function then, and it still does. It tells about the city values, the urban values. Now my people, we “peasants,” have come to the city, that is to say, we live with its values. There is a confrontation between old values of the tribes and new urban values. It’s confusing. There has to be a mode to do what the music did for blacks, what we used to be able to do with each other in private and in that civilization that existed underneath the white civilization. I think this accounts for the address of my books. I am not explaining anything to anybody. My work bears witness and suggests who the outlaws were, who survived under what circumstances and why, what was legal in the community as opposed to what was legal outside it. All that is in the fabric of the story in order to do what the music used to do. The music kept us alive, but it’s not enough anymore. My people are being devoured. Whenever I feel uneasy about my writing, I think: what would be the response of the people in the book if they read the book? That’s my way of staying on track. Those are the people for whom I write.

As a reader I’m fascinated by literary books, but the books I wanted to write could not be only, even merely, literary or I would defeat my purposes, defeat my audience. That’s why I don’t like to have someone call my books “poetic,” because it has the connotation of luxuriating richness. I wanted to restore the language that black people spoke to its original power. That calls for a language that is rich but not ornate.

LeClair: What do you mean by “address”?

Morrison: I stand with the reader, hold his hand, and tell him a very simple story about complicated people. I like to work with, to fret, the cliche, which is a cliche because the experience expressed in it is important: a young man seeks his fortune; a pair of friends, one good, one bad; the perfectly innocent victim. We know thousands of these in literature. I like to dust off these cliches, dust off the language, make them mean whatever they may have meant originally. My genuine criticism of most contemporary books is that they’re not about anything. Most of the books that are about something—the books that mean something—treat old ideas, old situations.

LeClair: Does this mean working with folklore and myth?

Morrison: I think the myths are misunderstood now because we are not talking to each other the way I was spoken to when I was growing up in a very small town. You knew everything in that little microcosm. But we don’t live where we were born. I had to leave my town to do my work here; it was a sacrifice. There is a certain sense of family I don’t have. So the myths get forgotten. Or they may not have been looked at carefully. Let me give you an example: the flying myth in Song of Solomon. If it means Icarus to some readers, fine; I want to take credit for that. But my meaning is specific: it is about black people who could fly. That was always part of the folklore of my life; flying was one of our gifts. I don’t care how silly it may seem. It is everywhere—people used to talk about it, it’s in the spirituals and gospels. Perhaps it was wishful thinking—escape, death, and all that. But suppose it wasn’t. What might it mean? I tried to find out in Song of Solomon.

In the book I’ve just completed, Tar Baby, I use that old story because, despite its funny, happy ending, it used to frighten me. The story has a tar baby in it which is used by a white man to catch a rabbit. “Tar baby” is also a name, like nigger, that white people call black children, black girls, as I recall. Tar seemed to me to be an odd thing to be in a Western story, and I found that there is a tar lady in African mythology. I started thinking about tar. At one time, a tar pit was a holy place, at least an important place, because tar was used to build things. It came naturally out of the earth; it held together things like Moses’s little boat and the pyramids. For me, the tar baby came to mean the black woman who can hold things together. The story was a point of departure to history and prophecy. That’s what I mean by dusting off the myth, looking closely at it to see what it might conceal. . . .

LeClair: Do you think it’s risky to do this kind of writing?

Morrison: Yes. I think I can do all sorts of writing, including virtuoso performances. But what is hard for me is to be simple, to have uncomplex stories with complex people in them, to clean the language, really clean it. One attempts to slay a real dragon. You don’t ever kill it, but you have to choose a job worth the doing. I think I choose hard jobs for myself, and the opportunity to fail is always there. I want a residue of emotion in my fiction, and this means verging upon sentimentality, or being willing to let it happen and then draw back from it. Also, stories seem so old-fashioned now. But narrative remains the best way to learn anything, whether history or theology, so I continue with narrative form.

LeClair: In the kind of fiction you have described, isn’t there a danger that it will be liked for something it is not? Are you ever worried about that?

Morrison: No. The people who are not fastidious about reading may find my fiction “wonderful.” They are valuable to me because I am never sure that what they find “wonderful” in it isn’t really what is valuable about it. I do hope to interest people who are very fastidious about reading. What I’d really like to do is appeal to both at the same time. Sometimes I feet that I do play to the gallery in Song of Solomon, for example, because I have to make the reader look at people he may not wish to look at. You don’t look at Pilate. You don’t really look at a person like Cholly in The Bluest Eye. They are always backdrops, stage props, not the main characters in their own stories. In order to look at them in fiction, you have to hook the reader, strike a certain posture as narrator, achieve some intimacy.

LeClair: As an editor, you look for quality in others’ work. What do you think is distinctive about your fiction? What makes it good?

Morrison: The language, only the language. The language must be careful and must appear effortless. It must not sweat. It must suggest and be provocative at the same time. It is the thing that black people love so much—the saying of words, holding them on the tongue, experimenting with them, playing with them. It’s a love, a passion. Its function is like a preacher’s: to make you stand up out of your seat, make you lose yourself and hear yourself. The worst of all possible things that could happen would be to lose that language. There are certain things I cannot say without recourse to my language. It’s terrible to think that a child with five different present tenses comes to school to be faced with those books that are less than his own language. And then to be told things about his language, which is him, that are sometimes permanently damaging. He may never know the etymology of Africanisms in his language, not even know that “hip” is a real word or that “the dozens” meant something. This is a really cruel fallout of racism. I know the standard English. I want to use it to help restore the other language, the lingua franca.

The part of the writing process that I fret is getting the sound without some mechanics that would direct the reader’s attention to the sound. One way is not to use adverbs to describe how someone says something. I try to work the dialogue down so the reader has to hear it. When Eva in Sula sets her son on fire, her daughter runs upstairs to tell her, and Eva says “Is?” you can hear every grandmother say “Is?” and you know: a) she knows what she’s been told; b) she is not going to do anything about it; and c) she will not have any more conversation. That sound is important to me.

LeClair: Not all readers are going to catch that.

Morrison: If I say “Quiet is as kept,” that is a piece of information which means exactly what it says, but to black people it means a big lie is about to be told. Or someone is going to tell some graveyard information, who’s sleeping with whom. Black readers will chuckle. There is a level of appreciation that might be available only to people who understand the context of the language. The analogy that occurs to me is jazz; it is open on the one hand and both complicated and inaccessible on the other. I never asked Tolstoy to write for me, a little colored girt in Lorain, Ohio. I never asked Joyce not to mention Catholicism or the world of Dublin. Never. And I don’t know why I should be asked to explain your life to you. We have splendid writers to do that, but I am not one of them. It is that business of being universal, a word hopelessly stripped of meaning for me. Faulkner wrote what I suppose could be called regional literature and had it published all over the world. It is good—and universal — because it is specifically about a particular world. That’s what I wish to do. If I tried to write a universal novel, it would be water. Behind this question is the suggestion that to write for black people is somehow to diminish the writing. From my perspective, there are only black people. When I say “people,” that’s what I mean. Lots of books written by black people about black people have had this “universality” as a burden. They were writing for some readers other than me.

LeClair: One of the complaints about your fiction in both the black and white press is that you write about eccentrics, people who aren’t representative.

Morrison: This kind of sociological judgment is pervasive and pernicious. “Novel A is better than B or C because A is more like most black people really are.” Unforgivable. I am enchanted, personally, with people who are extraordinary because in them I can find what is applicable to the ordinary. There are books by black writers about ordinary black life. I don’t write them. Black readers often ask me, “Why are your books so melancholy, so sad? Why don’t you ever write about something that works, about relationships that are healthy?” There is a comic mode, meaning the union of the sexes, that I don’t write. I write what I suppose could be called the tragic mode in which there is some catharsis and revelation. There’s a whole lot of space in between, but my inclination is in the tragic direction. Maybe it’s a consequence of my being a classics minor.

Related, I think, is the question of nostalgia. The danger of writing about the past, as I have done, is romanticizing it. I don’t think I do that, but I do feel that people were more interesting then than they are now. It seems to me there were more excesses in women and men, and people accepted them as they don’t now. In the black community where I grew up, there were eccentricity and freedom, less conformity in individual habits—but close conformity in terms of the survival of the village, of the tribe. Before sociological microscopes were placed on us, people did anything and nobody was run out of town. I mean, the community in Sula let her stay. They wouldn’t wash or bury her. They protected themselves from her, but she was part of the community. The detritus of white people, the rejects from the respectable white world, which appears in Sula was in our neighborhood. In my family, there were some really interesting people who were willing to be whatever they were. People permitted it, perhaps because in the outer world the eccentrics had to be a little servant person or low-level factory worker. They had an enormous span of emotions and activities, and they are the people I remember when I go to write. When I go to colleges, the students say “Who are these people?” Maybe it’s because now everybody seems to be trying to be “right.”

LeClair: Naming is an important theme in Song of Solomon. Would you discuss its significance?

Morrison: I never knew the real names of my father’s friends. Still don’t. They used other names. A part of that had to do with cultural orphanage, part of it with the rejection of the name given to them under circumstances not of their choosing. If you come from Africa, your name is gone. It is particularly problematic because it is not just your name but your family, your tribe. When you die, how can you connect with your ancestors if you have lost your name? That’s a huge psychological scar. The best thing you can do is take another name which is yours because it reflects something about you or your own choice. Most of the names in Song of Solomon are real, the names of musicians for example. I used the biblical names to show the impact of the Bible on the lives of black people, their awe of and respect for it coupled with their ability to distort it for their own purposes. I also used some pre-Christian names to give the sense of a mixture of cosmologies. Milkman Dead has to learn the meaning of his own name and the names of things. In African languages there is no word for yam, but there is a word for every variety of yam. Each thing is separate and different; once you have named it, you have power. Milkman has to experience the elements. He goes into the earth and later walks its surface. He twice enters water. And he flies in the air. When he walks the earth, he feels a part of it, and that is his coming of age, the beginning of his ability to connect with the past and perceive the world as alive.

LeClair: You mentioned the importance of sound before. Your work also seems to me to be strongly visual and concerned with vision, with seeing.

Morrison: There are times in my writing when I cannot move ahead even though I know exactly what will happen in the plot and what the dialogue is because I don’t have the scene, the metaphor to begin with. Once I can see the scene, it all happens. In Sula, Eva is waiting for her long lost husband to come back. She’s not sure how she’s going to feel, but when he leaves he toots the horn on his pear-green Model-T Ford. It goes “ooogah, ooogah,” and Eva knows she hates him. My editor said the car didn’t exist at the time, and I had a lot of trouble rewriting the scene because I had to have the color and the sound. Finally, I had a woman in a green dress laughing a big-city laugh, an alien sound in that small-town street, that stood for the “ooogah” I couldn’t use. In larger terms, I thought of Sula as a cracked mirror, fragments and pieces we have to see independently and put together. In Bluest Eye I used the primer story, with its picture of a happy family as a frame acknowledging the outer civilization. The primer with white children was the way life was presented to the black people. As the novel proceeded I wanted that primer version broken up and confused, which explains the typographical running together of the words.

LeClair: Did your using the primer come out of the work you were doing on textbooks?

Morrison: No. I was thinking that nobody treated these people seriously in literature and that “these people” who were not treated seriously were me. The interest in vision, in seeing, is a fact of black life. As slaves and ex-slaves, black people were manageable and findable, as no other slave society would be, because they were black. So there is an enormous impact from the simple division of color—more than sex, age, or anything else. The complaint is not being seen for what one is. That is the reason why my hatred of white people is justified and their hatred for me is not. There is a fascinating book called Drylongso which collects the talk of black people. They say almost to a man that you never tell a white person the truth. He doesn’t want to hear it. Their conviction is they are neither seen nor listened to. They also perceive themselves as morally superior people because they do see. This helps explain why the theme of the mask is so important in black literature and why I worked so heavily with it in Tar Baby.

LeClair: Who is doing work now that you respect?

Morrison: I don’t like to make lists because someone always gets left out, but in general I think the South American novelists have the best of it now. My complaint about letters now would be the state of criticism. It’s following post-modern fiction into self-consciousness, talking about itself as though it were the work of art. Fine for the critic, but not helpful for the writer. There was a time when the great poets were the great critics, when the artist was the critic. Now it seems that there are no encompassing minds, no great critical audience for the writer. I have yet to read criticism that understands my work or is prepared to understand it. I don’t care if the critic likes or dislikes it. I would just like to feel less isolated. It’s like having a linguist who doesn’t understand your language tell you what you’re saying. Stanley Elkin says you need great literature to have great criticism. I think it works the other way around. If there were better criticism, there would be better books.