Last week, President Barack Obama sent his 2017 budget to Congress, and—as is typical when government is divided—leading members of the other party declared it “dead on arrival.”

This time, however, they went a step further with the decision by the Senate and House Budget Committees to not hear testimony from the president’s budget director, Shaun Donovan, director of the Office of Management and Budget.

The massive distance between the parties grew starker this week when GOP leaders said they will refuse to consider a replacement for the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia. That would be unprecedented—and politically risky—but it continues a trend of the two parties growing farther apart on proper procedures of basic governance, such as passing budgets on time.

Yet compromise is still at the heart of our Constitution, even as our politics become ever more divisive. The budget process itself flows from this principle, regardless of dysfunction among lawmakers themselves. That’s precisely why Obama’s $4.1 trillion budget plan, even one composed by a lame duck president, is far from dead.

To understand why, we need to explore the budget process and what’s actually in the president’s proposals. I’d also like to shine a light on efforts at budget reform, which I’ve supported and researched as an academic and a practitioner.

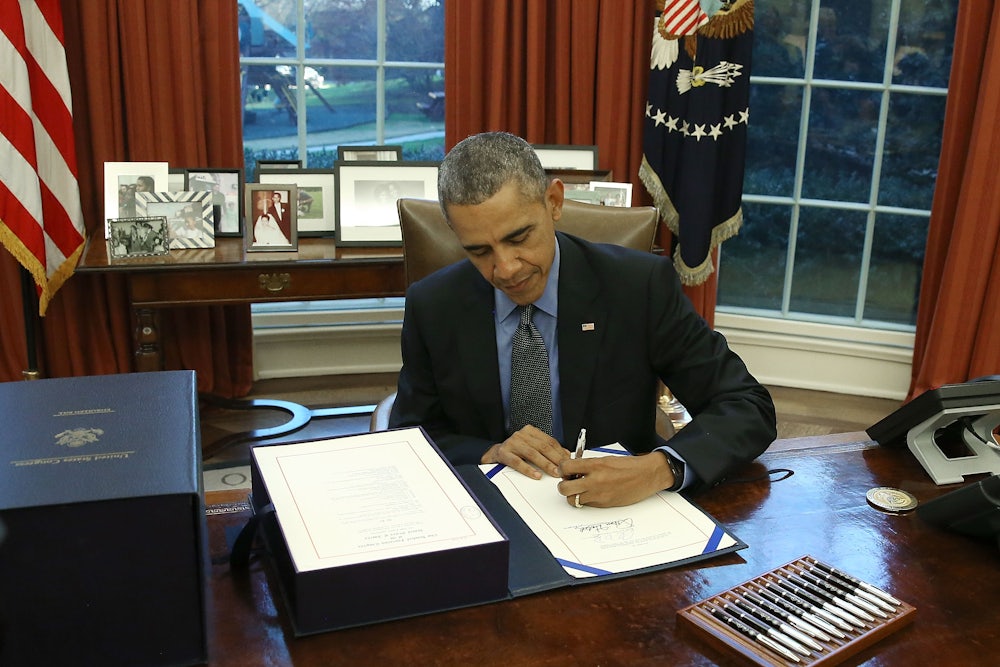

Should we judge this book by its cover?

One look at the budget’s cover might well raise questions about the president’s desire for compromise. Republicans may be wondering if it was intended to taunt them.

Usually budget covers have solid backgrounds in blue or green. But this year President Obama broke with tradition by embellishing his budget with a picture of the tallest peak in the United States, Mt. Denali. Once called Mt. McKinley, Obama renamed it by executive action last August, angering some Republicans for diminishing their former standard-bearer’s renown.

The White House emphasized that the image was meant to celebrate the administration’s executive actions on climate change, which were featured in the budget’s narrative.

Many Republicans still claim publicly that climate change will not happen, that the fact “Denali” is an anagram of “denial” is just a coincidence. But the choice of cover may be Obama’s way of signaling that he will continue to go it alone in his final year by issuing more executive actions rather than legislating through Congress.

It takes two

Obama’s ability to govern by executive orders alone is constrained because many executive orders are not “self-executing.” In other words, money is required for agencies to carry them out.

The Constitution grants the legislative branch the “power of the purse”; thus, Congress’ assent is necessary to change most spending priorities. Gaining such approval has been difficult for Obama since the Republicans retook control of Congress in the 2010 election—hence the executive actions, even if their effects are limited by insufficient funding.

Yet similarly, a Republican desire to go it alone—by passing spending plans that include large cuts—is also unrealistic. In the end, the president has a veto over appropriation bills, and can insist that executive priorities be included in those bills along with the legislature’s priorities.

Compromise between the branches, in other words, is essential for government budgeting.

This reality was ignored when President Richard Nixon insisted that he need not follow enacted appropriation bills. In response, Congress passed the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974, which reasserted its power over the purse.

But the act went beyond that by establishing a process for passing a so-called concurrent resolution—one that doesn’t require a president’s signature. This was a big shift from the Budget and Accounting Act of 1921, in which Congress tasked the president with proposing a comprehensive budget. Now Congress can attempt to set out its own broad vision, which may greatly differ from the president’s.

In nine of the last 18 years, however, Congress has failed to enact concurrent budget resolutions. And regardless of whether a concurrent resolution is adopted, Congress and the president still have to agree on appropriation bills and changes to other spending and tax laws to put a detailed budget into place.

House Speaker Paul Ryan, who has authored ambitious plans that would have drastically cut domestic discretionary and entitlement spending, has recently warned his party that if they want to pass the 12 regular appropriation bills on time (and then go home to campaign), they would have to accept the levels agreed to in 2015, rather than the lower levels now demanded by many of his Tea Party members.

Where agreement begins

The reasons behind Republicans’ sharp rhetorical response to the president’s budget are obvious but mask important ways in which Obama’s priorities are in tune with theirs.

Central to the GOP platform has long been a desire to cut spending to avoid excessive debt. Returning to this year’s budget cover, one Republican legislator dubbed it “literally a mountain of debt” (since it’s covered with cold, hard glaciers rather than cash, presumably he meant “figuratively”).

It’s true that Democrats want to increase domestic spending above the levels agreed to in 2015, yet some of the president’s proposals will be endorsed by Republicans despite their public rejection of all things Obama because both parties actually agree on their importance.

The best example of this is cybersecurity spending, which would rise 35 percent in the president’s budget in response to recent hacks by China, Russia and other countries. Other major proposals that have a good chance of being adopted include an expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit, and increased spending for cancer research and opioid abuse treatment. Republicans will probably also support the requested increase for maternal and child home visiting programs, an example of spending that research has shown to have significant benefits.

The largest spending increases and expanded tax preferences in the Obama budget are for clean energy and transportation, expanded child care and pre-K education, grants for college completion, reform of unemployment insurance and the creation of a wage insurance program. These aren’t likely to meet with much support on the other side of the aisle.

But despite the Republicans’ “mountain of debt” allusion, the White House proposals if adopted in full actually wouldn’t add to the deficit. The increased spending would be entirely offset, partly by spending cuts in other areas of the budget, but mostly by tax increases, including a $10.25 “fee” on each barrel of oil produced in the U.S. and restrictions on avoidance schemes used by the wealthy and businesses.

While that runs into another major plank of Republicans, lower taxes, it also hints at another area of broad agreement: the need to reform the tax code. Congressional leaders have said that this year they will draft reforms to business taxes in expectation of moving legislation in 2017. The proposals in Obama’s budget that would limit corporate tax “inversions” and “earnings stripping” will be a part of that discussion.

A realistic blueprint

But even where the two parties don’t agree, Republican appropriators will, as is always the case, have to rely on the extensive work put into developing the executive budget.

Each agency gives the relevant appropriations subcommittee a “justification book“ with hundreds and sometimes thousands of pages of detailed information on how it plans to spend its allocation. The staff resources of Congress are no match for this complexity, meaning it must concentrate on major items of dispute.

The administration also has an advantage in allocating spending to specific areas of the country, since Congress’ moratorium on earmarks tied its own hands.

In this campaign season, it should also be noted that deficit reduction advocates have judged Obama’s budget to be financially realistic, unlike the platforms of almost all of the other candidates. The tax reduction plans of Republicans would add trillions of dollars to our national debt, and the transition to Senator Sanders’ proposed single-payer health system would be massive compared with the relatively incremental approach of the Affordable Care Act.

Ultimately the Obama budget will leave an important legacy of policy proposals that have been scrutinized by the executive branch. This is particularly the case for the ongoing restructuring of the health care system. Many suggested health savings in President George W. Bush’s last budget were included in the Affordable Care Act.

Reforming the process

While budget realities will lead Congress to rely somewhat on the president’s budget, a bipartisan effort to reform the budget process is still essential.

Congress’s failure to budget effectively reached its nadir during the government shutdown of 2013. In recent years, various experiments with would-be “action-forcing triggers” did not lead to the results their users said they wanted. For example, refusing to increase the debt limit was not a practical threat; given that Congress had already permitted spending above the taxes it imposed, borrowing was necessary to close that financing gap.

Reformers have periodically suggested as an alternative to the concurrent resolution process a joint budget resolution, in which the president and the congressional leadership negotiate a general budget framework for the upcoming year—or in the case of a biennial process, for the next two years.

Ad hoc, limited versions of this biennial process were adopted in the Bipartisan Budget Acts of 2013 and 2015. Both acts increased caps on discretionary spending (the amounts provided by the appropriations committees) above the very low and politically unrealistic levels required by the Budget Control Act of 2011. That act created a bipartisan “supercommittee” tasked with reaching a specified amount of deficit reductions through tax and spending changes. Its members failed to agree, resulting in automatic spending cuts.

A delayed reaction to this mess is that there is now growing interest in creating a new “regular order” for the budget process. The House and Senate budget committees have started to hold hearings, and a group of experts called the National Budgeting Roundtable has been discussing reform options.

To be successful, reforms will have to restore norms of good budgeting, including that the two branches take each other seriously. While the odds are still long, it is possible that over the next year or two a major reform package will be developed that will be acceptable to both parties.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.