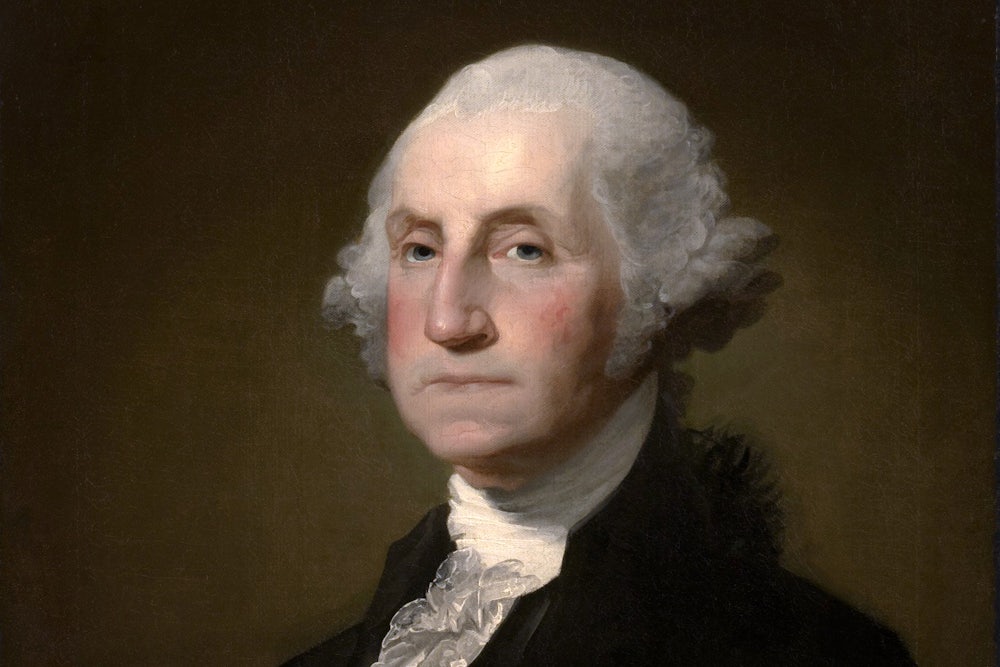

On the 250th anniversary of his birth, I called George Washington “the greatest man who ever lived.” I did not then know that William IV, the son of George III, used precisely those words about him, and what is more, refused to qualify them after Washington died. Of other contemporary judgments, perbaps that of Abigail Adams, never easily taken in by anyone, not even her husband, is the most sufficient: “Take his character together, and we shall not look on his like again.” Of today’s salutes, none is better than that of his biographer, James Thomas Flexner: “The gentlest of history’s great captains, one of the heroes of the human race.” The sheer greatness of the man may seem to make the contrast with the 41st, 40th, 39th, 38th . . . presidents unfair. We would be foolish to expect (or even wish) every president to be a Washington. But however embarrassing the contrast, it is legitimate to examine the qualities of the first president, “his character together,” which we may then justifiably take as a model in judging the presidents we elect, notably the one most recently elected.

Washington was continually in the field of action, where men usually show themselves at their worst. Set against him an Alexander, a Caesar, a Napoleon, a Lenin, and this one man, brilliant though many of the other Founding Fathers were, shines. He was the leader of a revolution both in war and peace, as general and statesman, who never (unlike most generals) cost by his actions one life more than was necessary. He was of commanding stature among his contemporaries. He was surrounded by temptations to overreach his power, for which he could many times have found justifications, as the Napoleons did, yet through a ceaselessly strenuous life in testing times he remained rooted in his shining humanity. That is why he is so approachable. We may contemplate him in wonder and gratitude, but not in awe. He is as we should try to be as citizens of a democracy, and as our presidents should at least try to be as his successors.

In picking out some of the qualities that enabled Washington to define the office of president, and in fact to bring the Constitution alive from the paper on which it was written, it is inevitable that one should overlook other qualities that others might choose to emphasize. The man was so various in his endowments that omission is almost dictated. Yet first among his qualities, surely, was his vision of the country. As striking as anything about him was that his eyes, for inspiration, were never turned east to Europe, unlike those of most of his contemporaries of his class. He only once left these shores, going to the West Indies on a matter of urgent family concern. He always looked to the west, from the moment he surveyed the Ohio Valley for Lord Fairfax, and beyond it to the vast continent he could imagine without seeing, and the mighty but beneficent nation that might be built there. We do not think of Washington as a great writer or even an eloquent orator. Yet his descriptions of the land he saw as a young surveyor rise to eloquence—majesty, if one likes—not least in the concrete detail of observation from which he drew and painted his picture of the promise of the beauty, fertility, grace, and sweetness of the land he saw. The emphatic lesson for our own time is that we always know from where Washington came—the land he knew and loved.

We in our time have not known from where Nixon, Ford, Carter, Reagan, and now George Bush came. Nixon was—is—a kind of displaced person in his own country, whether in California or New York City: hence his consternation at the first sign of rebellion in the people, his suspicion of his fellow countrymen, his distrust and fear of rivals and even of colleagues, his lack of confidence in the democratic process. Carter was less from the South than from Annapolis, less a peanut farmer than a Navy engineer, less religious than falsely biblical; disembodied. Reagan had a vision of America, but it was a construct; the images were mythical, of a supposed and idealized American golden age—an Eden, even—to which we were to return. George Bush is no more Kennebunkport, Maine, than Midland, Texas, no more Down East than Lone Star. It is their lack of true roots in a local place that accounts for the poverty of their national vision, as in Bush’s inaugural address, so that they seem to be servants only to the special interests that promote their careers. In his first hundred days Bush is, as he always has been, a butler to the interests he serves, dry cleaner to a democracy.

Another of Washington’s qualities as a statesman was that he did not think it his or any government’s business to check on the private lives or morals of his countrymen. In many ways a model of personal decorum, with some engaging lapses of the heart and more regularly with the bottle, he left the people generally to pursue their often unruly lives, while governing them in necessary things with his wise and austere authority. The idea of the “virtuous citizenry” that some conservatives now like to say underpinned the republican experiment is simply not borne out by any historical evidence or even by any commonsense expectations. Much went on in the homes of rich and poor alike to make one raise one’s eyebrows, however primly these people walked to church on Sundays. The virtuous citizen existed only in his capacity as a citizen, exercising his freedoms, without the prying of government, and accepting his obligations to the political order that guaranteed them. Recent presidents demean their own office as well as the people by thinking it their duty to preach of “family values,” or the duty of their wives (imagine Martha Washington doing it!) to instruct us, “Just say No.” On drugs, crime, education, ethics in government, Bush always resorts to kind and gentle pleas for individual moral regeneration, in the absence of any willingness to confront tough policy choices, especially economic remedies, that might have some effect. Washington sought the hard solutions.

In an unruly time, at the birth of the nation, Washington could tolerate unruliness. When this then-experimental federal structure was endangered, Washington put his foot down, magisterially as usual, not only himself but through men like Marshall on the Supreme Court. But otherwise he understood as well as Jefferson that there must in a democracy be a “whiff of a little rebellion in the air.” He could live with the untidiness of a democracy and a free people. (He had to live and march with a ragtag and bobtail of an army, constantly deserting for the summer to attend to the harvest at home.) In contrast with today’s presidents, he understood the remark of the 18th-century American conservative Fisher Ames (paraphrased into modern vocabulary): the autocratic monarchies were like great ships that sailed majestically on, until they struck a rock and sank forever, whereas democracy is like a raft—it never sinks but, damn it, your feet are always in the water. Washington in his whole two terms did not distract himself, his administration, or the people by exhibiting puppies so that his presidency might be patted.

It was not only the people and the states who were unruly. No president, at least until the days preceding the Civil War, held together so many talented, factious, scheming colleagues. His eventual disdain for Jefferson (of which Jefferson in his vanity seems to have been unaware to the end), as near to bitterness as Washington could come, was provoked (justifiably) by the incapacity of Jefferson to be simply loyal. Otherwise Washington put up with and kept in harness a ministry of some of the most ambitious and brilliant men ever to compose a Cabinet, in any nation in any age. That set the standard that Bush, like his immediate predecessors, refuses to try to meet: a fully mature man as president who could act as a statesmen while allowing his colleagues to gallop sometimes in all directions. What Washington realized was that if you wish to govern well an energetic people, you must expect the people, unruly themselves, to throw up energetic and unruly leaders. They all tell you something you need to hear. The last president with this gift was of course FDR.

It is false to judge a politician by his reading. (Jefferson read too much too glibly, and often spoke and wrote too much too glibly.) Yet it is important to know that our politicians understand what literature and ideas are. Go to Mount Vernon and look at Washington’s library. Or read his letters, full of obviously informed references to some classical author, drawing an example that should be followed or a warning that should be foreseen. As with all the Founding Fathers, Washington belonged to, he respected, he was cultured in, the heritage of Western civilization, its literature, its thought, and its history, to which the new nation was the heir.

It is now exactly 200 years since George Washington was installed as the first President of the United States, and we remember him still for “his character together.” History will doubtless not be so kind to George Bush. Yet the question we have to ask about Bush’s first hundred days, and about his immediate predecessors, is not what is so dismaying to one’s soul about them, but what is wrong with our soul that we expect and demand no better in our leaders.