The Democratic primary is being defined—and could be decided—by a generational divide. Young voters are flocking to Bernie Sanders, as countless articles point out, and the results in Iowa back this up: Sanders won caucus voters under 30 by an astounding 70-point margin, while Hillary Clinton won those over 65 by 43 points. The theories given for this divide are myriad. Many young voters see Clinton as a corrupt or untrustworthy insider, whereas Sanders “seems sincere.” Many older voters, meanwhile, find Sanders’s policies impractical and see in Clinton a historic opportunity to elect the first female president. But all these arguments seem to agree on one thing: Sanders is leading a semi-socialist insurgency against the party establishment.

Surveying one hundred years of history, though, the question is not why younger voters are embracing Sanders’s populist revolution, but why the Baby Boomer generation came to believe that Bill and Hillary Clinton—with their close ties to big business—should become the standard-bearers for the nation’s liberal party. In other words, Bernie’s millennial army isn’t the generational exception. Hillary’s Boomers are.

Transported to the early part of the previous century, Sanders’s positions and rhetoric would sound a lot more traditionally Democratic than Clinton’s. Consider his New Hampshire victory speech, where he said, “Tonight, we served notice to the political and economic establishment of this country that the American people will not continue to accept a corrupt campaign finance system that is undermining American democracy, and we will not accept a rigged economy in which ordinary Americans work longer hours for lower wages, while almost all new income and wealth goes to the top 1 percent.” That’s much closer to progressive Democratic forebears like William Jennings Bryan (the party’s presidential nominee in 1896, 1900, and 1908) and Franklin Roosevelt (president from 1933 to 1945) than Hillary Clinton is.

What changed? The fundamental makeup of the American economy.

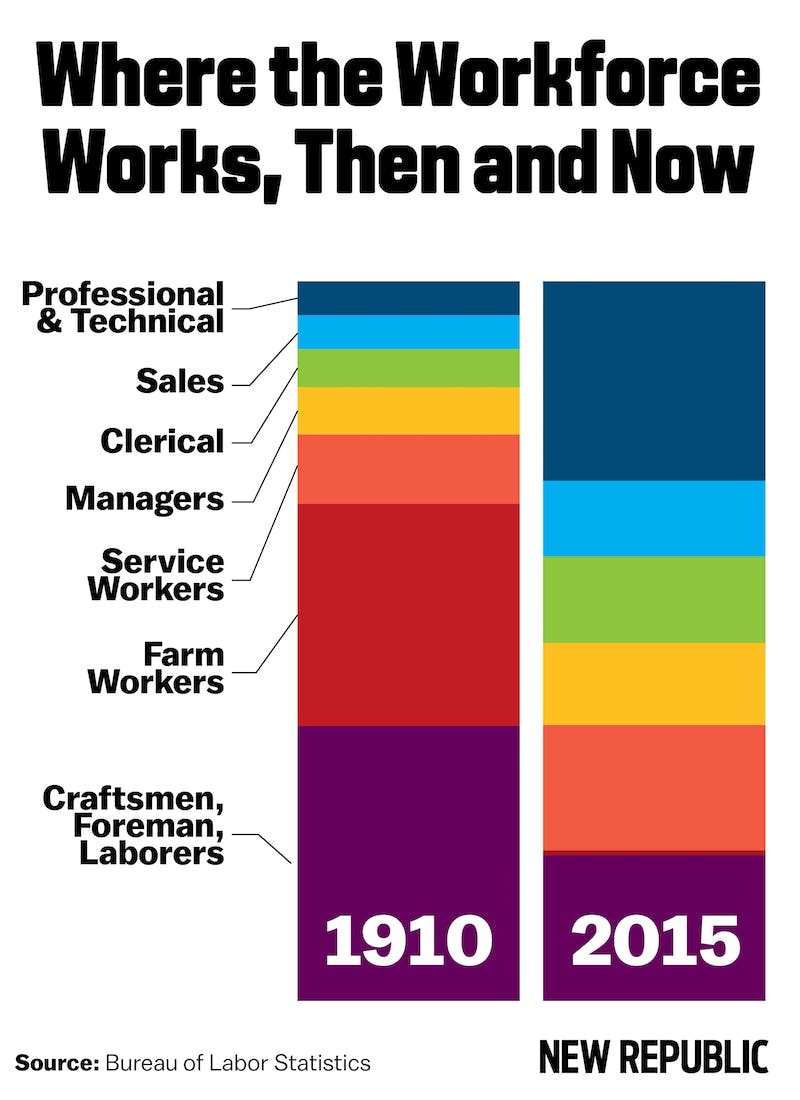

Data from the Bureau of Labor

Statistics makes clear how few professional options most people had in the first

half of the twentieth century. In 1910, fewer than 15 percent of people worked

in managerial or professional roles. The great majority worked in manual jobs,

and had no ladder to climb.

The post-war Baby Boomer generation profoundly transformed the economy. In 1977, sociologists Barbara and John Ehrenreich argued that the middle of the twentieth century was marked by the ascendance of the Professional-Managerial Class. They defined this group as “mental workers who do not own the means of production,” which includes teachers, journalists, nurses, social workers, managers of all sorts, mid-level executives, government workers, and many others.

During the young adulthoods of the Boomers, government policies made it easier for young people to join the PMC. Public colleges were inexpensive, and students graduated with little debt. Labor unions provided jobs like teacher and nurse a great deal of career stability. Very high marginal tax rates on very high earners encouraged companies to invest in younger workers. And a middle-class society based on manufacturing and construction encouraged dispersion into all sections of the country, which kept housing prices modest.

The relative ease of joining the middle class helps explain an anomaly of the Boomer generation of Democrats—the expunging of most class-based rhetoric. Jennings Bryan and Roosevelt regularly criticized finance and big business, sometimes even calling into question the morality of the very wealthy. Democrats of the sixties and seventies found a happy medium: subsidizing ways to join the middle class, not demonizing those at the top.

The Boomer generation undid many of the policies that had encouraged ascension to the PMC, and allowed workers to flourish in these careers. Welfare reform and free trade agreements undermined the bargaining positions of workers by giving workers less to fall back on and managers more options abroad. Increasing the costs of public education and asking students to finance those costs with debt left the next generation of workers with a heavy burden as they joined the PMC.

More importantly, changes in professional norms and economic expectations have made joining the PMC an increasingly grim prospect. Teachers, who for decades enjoyed great autonomy in designing lesson plans and nurturing students, have faced an assault from the business community demanding they teach to standardized tests. Nurses and other professionals have seen their unions lose clout within the Democratic Party. And government workers are maligned as a waste of taxpayer money.

Even among elite PMC careers, workers are seeing much of their professional autonomy removed. Forty years ago, most lawyers worked in individual practice or small firms. Now, young lawyers are more likely to work for huge corporate law firms for very long hours doing depressing work like “document review,” all because they have no other choice if they want to pay back their mortgage-sized student loans. For the first seven years of a career as an investment banker, a young associate may work 90 hours a week—to support a Boomer managing director, who may only work 60. Young college professors are much more likely to be part-time and non-tenure track than Boomer professors were at the same points in their careers, leading to increased militancy among adjunct professors.

In short, PMC jobs, especially for younger workers, increasingly resemble the crappy jobs of the beginning of the twentieth century. They have the proletarian character of the same monotonous thing day after day: spreadsheets, multiple-choice tests, document review. These changes in professional work mean we can no longer avoid the issue of class. Some economic groups have very different interests from others, and society generally is set up to benefit those at the top.

This has been the essential message of Sanders’s campaign: that the game is rigged, and the only thing to do is take on the employers. Her very recent adoption of that rhetoric notwithstanding, Clinton believes you can play the game and climb the ladder—that Americans should fight for their careers, not fight their employers. She has embraced the corporations and elite groups that determine these career trajectories, and won the support of Wall Street billionaires like George Soros and Warren Buffett.

The heyday of the PMC may represent the anomalous decades, and the Boomers the one generation that happened to benefit from its rise. That Sanders sounds so much like Democrats from a century ago may mark a return to normalcy in which the Democratic Party fights for average people without career choices. Most young Democrats are already there.