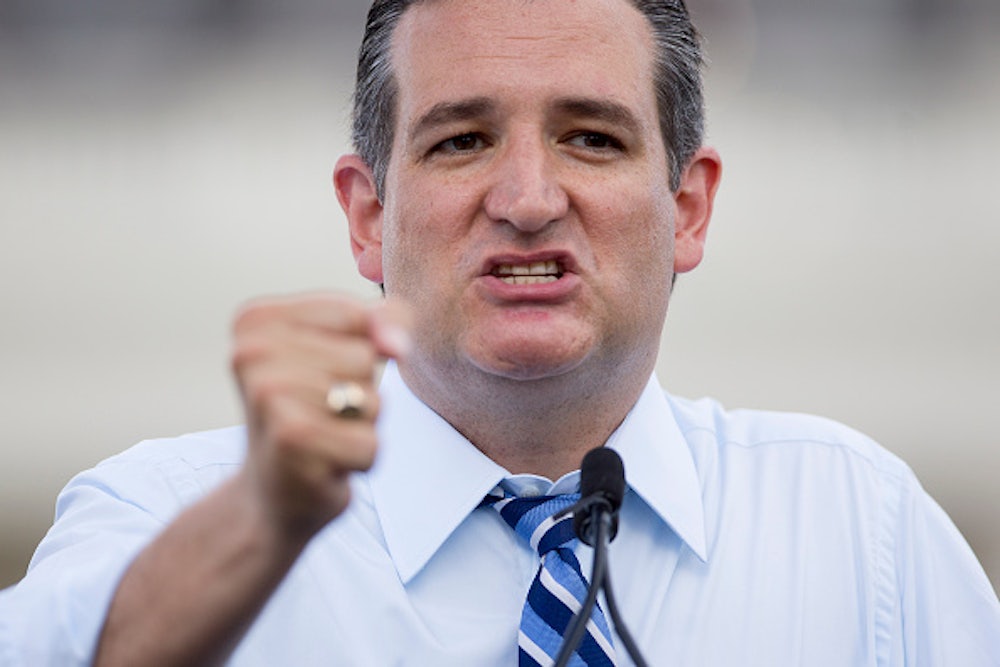

A little over a decade ago, Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott embarked on a vigorous effort to prosecute voters under a new and little-known provision of state law that in some cases forbids a person from carrying the completed absentee ballot of another voter. Get-out-the-vote organizers, who had been assisting elderly and infirm voters, were suddenly coming under criminal investigation for handling someone else’s ballot. And Ted Cruz, who was then Abbott’s Solicitor General, vigorously backed the effort. As Cruz vies for the presidency, this chapter in his political history has received little attention.

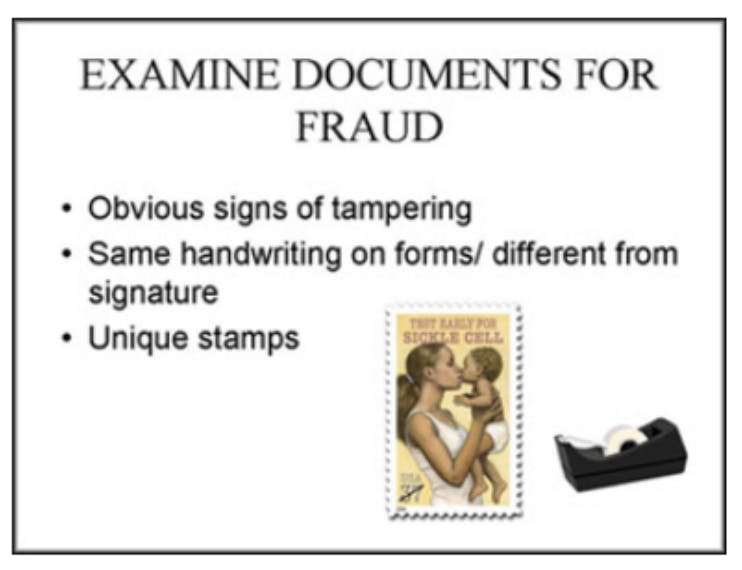

As the number of cases mounted, critics began to cry foul that the highly technical charges were mostly being deployed against black and Hispanic Democrats. In September 2006, the state Democratic party, and several subjects of Abbott’s actions, filed a civil rights suit against the state claiming that Abbott had launched a calculated attack on the access of minority populations to the polls. As evidence, the plaintiffs had discovered a PowerPoint presentation that Abbott’s office had used for training officials to enforce the voting laws. The presentation included imagery of African Americans going to vote; it also encouraged officers to place increased scrutiny on voting envelopes bearing stamps that raise awareness about sickle-cell anemia, a blood cell disease that particularly affects African Americans. The lawsuit alleged that the Attorney General’s office had questioned voters about this type of stamp in investigating two African-American plaintiffs.

Cruz would have none of it. “This lawsuit has no basis in law—the plaintiffs are a combination of political operatives and individual criminals who have already pleaded guilty to voter fraud,” Cruz said in a statement, referring to two plaintiffs from which his office had extracted guilty pleas. “We will vigorously defend this baseless lawsuit to ensure that admitted criminals like the plaintiffs will not be able to defraud Texas voters and undermine the integrity of Texas elections.”

The Lone Star Project, a progressive advocacy group that supported the lawsuit, fired back, calling Cruz’s language abusive and misleading, pointing out that the guilty pleas had nothing to do with fraudulent activity but were simply an admission that two Texans had carried another person’s ballot in the process of providing voter assistance. “Cruz’s verbal attack is another calculated tactic to suppress minority vote,” the group asserted.

Six weeks later, a federal judge took the rare step of ordering the Attorney General to cease his enforcement action of the law against people who had “merely possessed” a ballot or official envelope with a voter’s consent.

“Its criminal penalties and disqualification of the vote for the mere possession of a ballot or carrier envelope are not necessary to achieve the State’s interest in curtailing fraud [...]” wrote John Ward, a federal district judge in eastern Texas. “Historically, individuals, political parties, and other organizations in certain communities have attempted to maximize voter turnout by assisting voters in casting their mail-in ballots.”

But within a week, a three-judge panel on the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, one of the country’s most conservative federal appeals courts, struck down Ward’s ruling and allowed the Texas prosecutions to move forward. Cruz applauded the Fifth Circuit’s ruling. “Texans can rest assured that the integrity of our elections will be protected,” he said in a statement. “The Office of the Attorney General remains fully committed to enforcing state voter fraud laws and will continue protecting everyone’s right to vote.”

The state didn’t remain “fully committed” to this unfair aspect of the law for very long. By 2008, Abbott had quietly ceased his investigations of two plaintiffs. And in May of that year, shortly after Cruz left the Solicitor General’s office, Abbott opted to settle the civil rights lawsuit brought against his office. Twenty-six of the voter fraud cases, according to reporting from the Dallas Morning News, had been brought “against Democrats, and almost all involving blacks or Hispanics,” a charge that the state disputed in a court filing.

As a condition of the settlement, the attorney general’s office adopted a new set of prosecution guidelines that limited which types of ballot possession cases the state could prioritize. Democrats said that the new guidelines would ensure that the office would pursue no additional cases resembling those against the two Texans who pled guilty to merely assisting voters by carrying their completed ballots—the people whom Cruz called criminals and fraudsters.

Greg Abbott, now the governor of Texas, did not respond to requests for comment. In response to a list of questions, the Texas Attorney General’s office sent three spreadsheets listing voter fraud cases and referrals. The spreadsheets did not include racial information. Apparently, even after it has had to settle a lawsuit centering on racially discriminatory election law enforcement, the Texas Attorney General still does not keep data on the race of those it prosecutes under the laws. Ted Cruz’s Senate office referred me to his presidential campaign, which did not respond to multiple calls and emails.

This week I spoke with Willie Ray, a 78-year-old city council member in Texarkana, Texas. Ray was one of the people Cruz was referring to when mentioned the guilty pleas in the voter fraud prosecutions.

“My whole thing was to help people, to go out and get people what they needed,” Ray told me, adding that she believed the attorney general’s actions amounted to an effort to dampen her community’s electoral participation. “They came in and did a hard job on us.”

“I’m not going to deny that I assisted people,” Ray said. “I know I never did anything wrong.”