While keeping our eyes on the cataclysms in Europe

and Asia, we have lost sight of a tragedy nearer

home. A hundred thousand rural households have heen uprooted

from the soil, robbed of their possessions—though by strictly legal methods—and turned out on the highways.

Friendless, homeless and therefore voteless, with fewer

rights than medieval serfs, they have wandered in search

of a few days’ work at miserable wages—not in Spain or

the Yangtze Valley, but among the vineyards and orchards

of California, in a setting too commonplace for a color

story in the Sunday papers. Their migrations have heen

described only in a long poem and a novel. The poem is

“Land of the Free,” by Archibald MacLeish, published last

year with terrifying photographs by the Resettlement Administration.

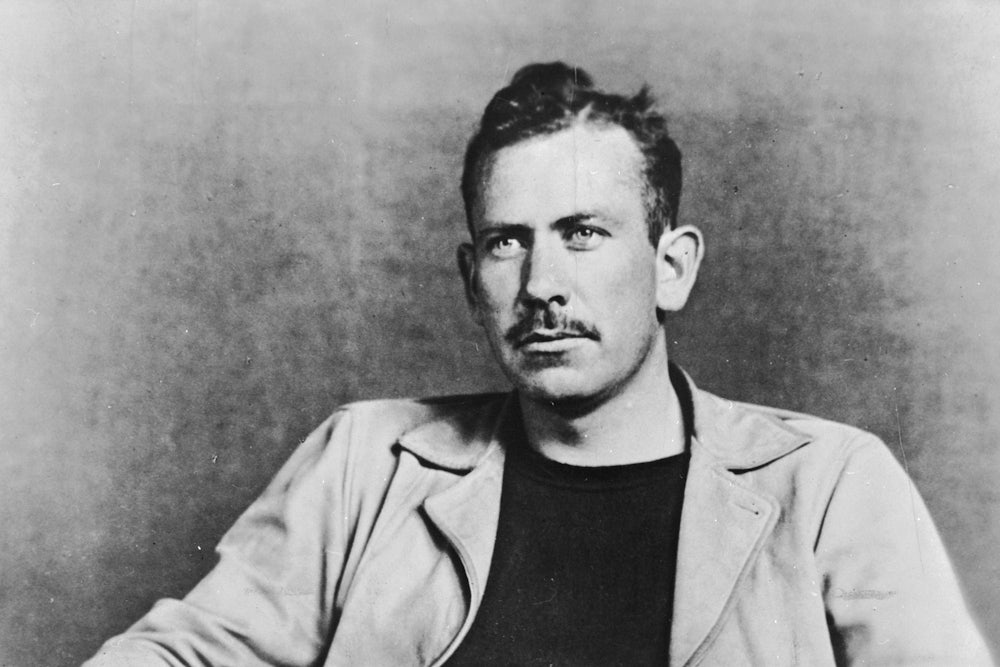

The novel, which has just appeared, is John

Steinbeck’s longest and angriest and most impressive work.

The Grapes of Wrath begins with Tom Joad’s homecoming. After being released from the Oklahoma State Penitentiary, where he has served four years of a seven-year sentence for homicide, he sets out for his father’s little farm in the bottom lands near Sallisaw. He reaches the house to find that it is empty, the windows broken, the well filled in and even the dooryard planted with cotton. Muley Graves, a neighbor, comes past in the dusk and tells him what has happened. It is a scene that I can’t forget: the men sitting hack on their haunches, drawing figures with a stick in the dust; a half-starved cat watching from the doorstep; and around them the silence of a milelong cottonfield. Muley says that all the tenant farmers have been evicted from their land—“tractored off” is the term he uses. Groups of twenty and thirty farms are being thrown together and the whole area cultivated by one man with a caterpillar tractor. Most of the families are moving to California, on the rumor that work can he found there. Tom’s people are staying temporarily with his Uncle John, eight miles away, but they will soon be leaving. Of this whole farming community, no one is left but stubborn Muley Graves, hiding from the sheriff’s men, haunting empty houses and “jus’ wanderin’ aroun’,” he says, “like an ol’ graveyard ghos’.”

Next morning Tom rejoins his family—just in time, for the uncle too has been ordered to leave his farm. The whole family of twelve is starting for California. Their last day at home is another fine scene in which you realize, little by little, that not only a family but a whole culture is being uprooted—a primitive culture, it is true, but complete in its fashion, with its history, its legends of Indian fighting, its songs and jokes, its religious practices, its habits of work and courtship; even the killing of two hogs is a ritual.

With the hogs salted down and packed in the broken-down truck among the bedclothes, the Joads start westward on U. S. Highway 66. They are part of an endless caravan—trucks, trailers, battered sedans, touring cars rescued from the junkyard, all of them overloaded with children and household plunder, all wheezing, pounding and screeching toward California. There are deaths on the road—Grampa is the first to go—but there is not much time for mourning. A greater tragedy than death is a burned-out bearing, repaired after efforts that Steinbeck describes as if he were singing the exploits of heroes at the siege of Troy. Then, after a last wild ride through the desert—Tom driving, Rose of Sharon and her husband making love and Gramma dying under the same tarpaulin—the Joads cross the pass at Tehachapi and see before them the promised land, the grainfields golden in the morning.

The second half of the novel, dealing with their adventures in the Valley of California, is still good but somewhat less impressive. Until that moment the Joads have been moving steadily toward their goal. Now they discover that it is not their goal after all; they must still move on, but no longer in one direction—they are harried by vigilantes, recruited as peach pickers, driven out again by a strike; they don’t know where to go. Instead of being just people, as they were at home, they hear themselves called Okies—“and that means you’re scum,” they tell each other bewilderedly. “Don’t mean nothing itself, it’s the way they say it.” The story begins to suffer a little from their bewilderment and lack of direction.

At this point one begins to notice other faults. Interspersed among the chapters that tell what happened to the Joads, there have been other chapters dealing with the general plight of the migrants. The first half-dozen of these interludes have not only broadened the scope of the novel but have been effective in themselves, sorrowful, bitter, intensely moving. But after the Joads reach California, the interludes are spoken in a shriller voice. The author now has a thesis—that the migrants will unite and overthrow their oppressors—and he wants to argue, as if he weren’t quite sure of it himself. His thesis is also embodied in one of the characters: Jim Casy, a preacher who loses his faith but unfortunately for the reader can’t stop preaching. In the second half of the novel, Casy becomes a Christlike labor leader and is killed by vigilantes. The book ends with an episode that is a mixture of allegory and melodrama. Rose of Sharon, after her baby is born dead, saves a man from starvation by suckling him at her breast—as if to symbolize the fruitfulness of these people and the bond that unites them in misfortune.

Yet one soon forgets the faults of the story. What one remembers most of all is Steinbeck’s sympathy for the migrants—not pity, for that would mean he was putting himself above them; not love, for that would blind him to their faults, but rather a deep fellow feeling. It makes him notice everything that sets them apart from the rest of the world and sets one migrant apart from all the others. In the Joad family, everyone from Grampa—“Full a’ piss an’ vinegar,” as he says of himself—down to the two brats, Ruthie and Winfield, is a distinct and living person. And the story is living too—it has the force of the headlong anger that drives ahead from the first chapter to the last, as if the whole six hundred pages were written without stopping. The author and the reader are swept along together. I can’t agree with those critics who say that The Grapes of Wrath is the greatest novel of the last ten years; for example, it doesn’t rank with the best of Hemingway or Dos Passos. But it belongs very high in the category of the great angry books like Uncle Tom’s Cabin that have roused a people to fight against intolerable wrongs.