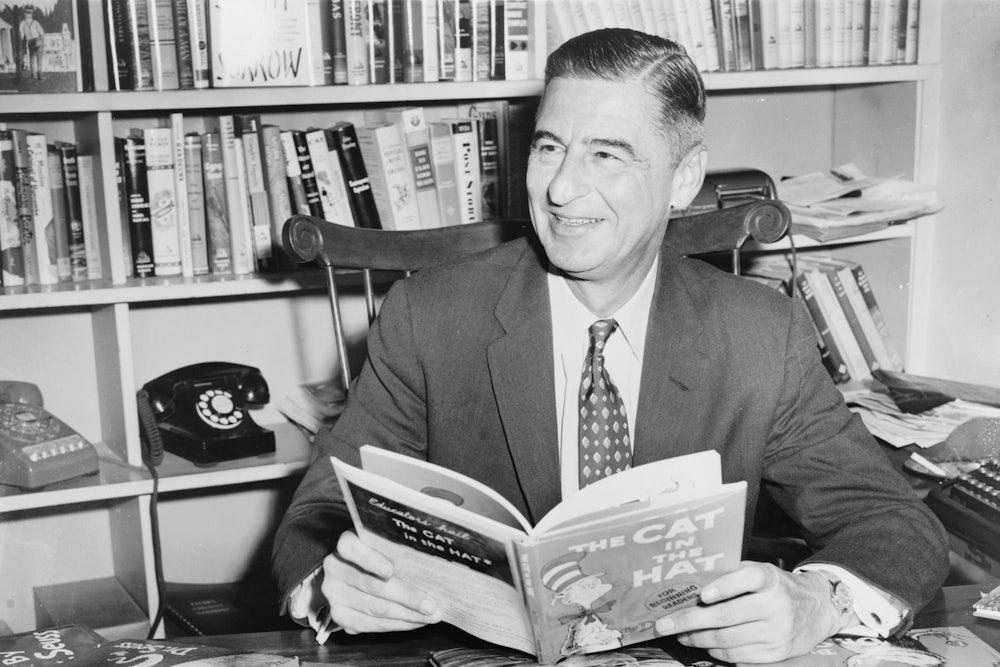

Others may disagree, but in my opinion a crucial turning point in the development of Dr. Seuss’s thought came with the publication of Horton Hears a Who (1954). You will recall the plot. Horton, an elephant, discovers a tiny civilization on a dust spot and protects it from other animals smaller than he but larger than it. Clearly this is an allegory for great-power responsibility in the world. But Dr. Seuss’s current interpreters, including his own publisher, prefer to see it as a story that “lampoons social snobbery,” because of its emphasis on the rights of little people. With this book, then, the author makes his transition from the old issues of the older generation to the new ideas of the 1950s.

Consider. The King’s Stilts (1939) is unabashedly Reaganite. It celebrates a folksy national leader who quits work at five o’clock in order to relax. The enemy is government bureaucracy, represented by old Droon, who grinds out burdensome regulations for the King’s signature. (“Sign here . . . sign there . . . Sire, hurry. There are hundreds more to come.”) Droon ends badly.

In Horton Hatches the Egg (1940, and Seuss’s masterwork, in my judgment), the theme is welfare dependency, symbolized by “Mayzie, a lazy bird” who abandons her child and moves to Palm Beach when offered free day care. Horton (the very same) is the spirit of Republican private-sector initiative, with his stalwart cry, “I meant what I said and I said what I meant. / An elephant’s faithful one hundred percent!” In his book, Anarchy, State and Utopia, libertarian philosopher Robert Nozick has ably analyzed Thidwick, The Big-Hearted Moose (1948) as a defense of individual liberty against the claims of collectivism. (One wonders, though, whether Thidwick, qua moose, isn’t also a symbol of big government.)

By the late 1950s, Dr. Seuss’s new drift is dear. Yertle the Turtle (1958), about the rise and fall of a dictator, complacently assumes that tyranny can be vanquished by a small burp. (Had he learned nothing from Hungary, two years before?) The Lorax (1971) pits an Ansel Adams-like environmental prophet against a callous industrialist, who growls “business is business! / And business must grow” shortly before chopping down the last Trufella Tree.

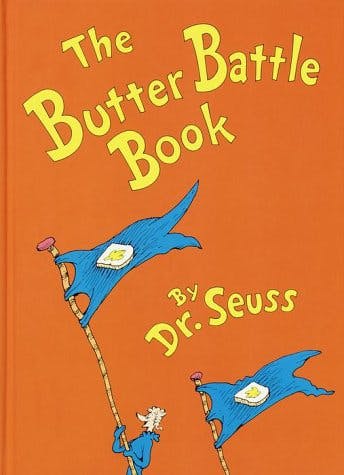

Perhaps this history will add a little perspective to the public discussion of Dr. Seuss’s latest treatise, The Butter Battle Book (Random House, $6.95 in washable hardcover), in which the good doctor turns to the issue of war and peace. Art Buchwald has called it “must reading.” Coretta Scott King says, “May the wisdom of this book help parents double their efforts for world peace.” And Joan Ganz Cooney of the Children’s Television Workshop says the book “has brilliantly dramatized for children the number one issue of our age.”

The number one issue of our age is not cholesterol. The Butter Battle Book concerns two nations, the Zooks and the Yooks (no Gooks need apply), separated by a wall and a minor cultural difference: Zooks prefer their bread butterside-down, whereas Yooks prefer it butter-side-up. Because of this difference, the narrator’s grandfather tells him, “you can’t trust a Zook . . . / Every Zook must be watched! / He has kinks in his soul!” Patrolling the wall with a Snick-Berry Switch, a Yook is disarmed by a Zook with a slingshot. He responds with a Triple-Sling Jigger, which is met by a Jigger-Rock Snatchem, and so on, until each side stands ready to drop a Bitsy Big-Boy Bomberoo on the other.

The story is told in flashback from the moment of crisis. The drawings are uncharacteristically gloomy and autumnal. Also uncharacteristic is the existential, cliff-hanger ending. “Dr. Seuss’s Bleak Polemic,” The New York Times calls it. “[C]aricatures too close to contemporary international reality for comfort,” says the Times reviewer, Betty Jean Lifton.

But examined in light of modern international relations theory and practice. Dr. Seuss’s paradigm is defective. Take, for example, a present-day situation that may never have occurred to Dr. Seuss: the cold war between the Soviet bloc and the Western alliance. The sad dilemma of the Zooks and the Yooks differs from this standoff in at least three ways.

First, Zooks and Yooks disagree about which side their bread is buttered on. Americans and Soviets disagree about democracy and freedom, among other questions of etiquette. This is why Dr. Mary Calderone’s wish for this book—“that on New Year’s Day [why?] a Russian version will be wrapped in brown paper and tossed over the transom of every door in Russia”—is unlikely to come true. Second, the wall between the Yooks and the Zooks just grew. Someone built our wall, and we have reason to suspect that many on the other side would actually prefer their bread butter-side-up, if given the option, which they aren’t. Third, neither Yooks nor Zooks seem to have the slightest desire to impose their bread-buttering habits on the opposing party. We, on the other hand, have some cause for concern that without the odd Triple-Sling Jigger, we’d soon be buttering our bread very differently.

I belabor these points only because lesser thinkers than Dr. Seuss have also been suggesting lately that the Cold War is really about nothing at all, and that all we need to end it is for everybody to take a cold shower and cease this madness. Obviously it’s worth working and risking for peace. But I worry that children may fail to explain to their parents that peace will not be as easy to come by in our world as in the world of the Yooks. The Butter Battle Book is a sad illustration of one of Orwell’s favorite themes: the corrosive effect of politics on literature. Compared to Dr. Seuss’s earlier classics the drawings are tired, and the poetry is lame. (Those Boys in the Back Room sure knew how to putter! / They made me a thing called the Utterly Sputter / and I jumped aboard with heart all aflutter. . . .) He even borrows a nonsense phrase (“Kick-a-poo”) without credit from the late Al Capp. Doctor, doctor. Heal thyself.