On Monday, February 29, a judge in Monroe County, Alabama sealed Harper Lee’s will from public view. The motion was filed by the Birmingham law firm Bradley Arant Boult Cummings, which was acting on behalf of Tonja Carter, Lee’s lawyer and the executor of her estate.

The decision to seal the will became public last Friday, and it was immediately controversial. This has been true of every legal move involving Lee and Carter over the last few years, even before the furor following the announcement, in February of last year, that Carter had “discovered” a lost sequel to To Kill a Mockingbird.

Harper Lee was legendarily press-averse—interview requests after the mid-1960s were typically met with responses ranging from “no” to “hell no”—and indeed, Judge Greg Norris, who sealed the will, based his judgment on the need for privacy: “It is not the public’s business what private legacy she left for the beneficiaries of her will.”

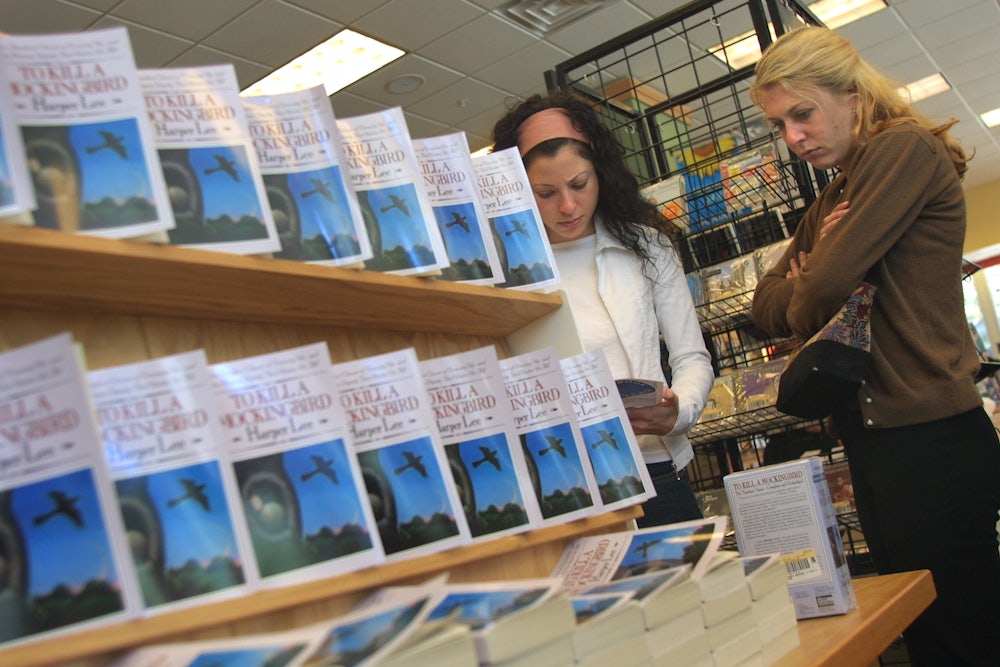

We may never know what Lee’s will stipulates, but the estate’s first action in the wake of Lee’s death is both bold and somewhat baffling: The New Republic has obtained an email from Hachette Book Group, sent on Friday, March 4 to booksellers across the country, revealing that Lee’s estate will no longer allow publication of the mass-market paperback edition of To Kill a Mockingbird.

According to the email, which a number of booksellers in multiple states have confirmed that they received a variation of, no other publisher will be able to produce the edition either, meaning there will no longer be a mass-market version of To Kill a Mockingbird available in the United States. Mass-market paperbacks are smaller and significantly cheaper than trade paperbacks—sometimes called “airport books,” mass-market paperbacks are typically available in non-bookstore retail outlets, like airports and supermarkets. The most popular mass-market paperback of the last few years is almost certainly the stout paperbacks of George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series. Another place people are likely to encounter mass-market paperbacks is in schools, where they are popular due to their low cost.

The email contains a discount code for the mass-market paperback effective Tuesday, March 1, one day after Lee’s will was sealed—Hachette has to liquidate its stock, since it will only be able to sell its edition for a limited amount of time, so it’s offering an additional discount for booksellers. A spokesperson for Hachette confirmed that they were ceasing publication of the mass-market paperback of To Kill a Mockingbird.

While Hachette only published the mass-market paperback of To Kill a Mockingbird, HarperCollins publishes the trade paperback, hardcover, and special editions of To Kill a Mockingbird, and also published Go Set a Watchman last year. Asked for comment, a spokesperson for HarperCollins, which publishes the trade paperback edition of To Kill a Mockingbird said that the company “will continue to publish the editions that we have.” HarperCollins’s editions of To Kill a Mockingbird ranges in price between $14.99 and $35. As Michael Cader and Peter Ginna have pointed out, Hachette licensed the rights to the book from HarperCollins, which meant that Harper Lee and HarperCollins split the royalties earned from the mass-market paperback. Now, the Lee estate will earn full royalties from every copy sold.

Why does this matter? Mass-market books are significantly cheaper than their trade paperback counterparts. Hachette’s mass-market paperback of TKAM retails for $8.99, while the trade paperbacks published by Hachette’s rival HarperCollins go for $14.99 and $16.99. Unsurprisingly, the more accessible mass-market paperback sells significantly more copies than the trade paperback: According to Nielsen BookScan, the mass-market paperback edition of To Kill a Mockingbird has sold 55,376 copies since January 1, 2016, while HarperCollins’s trade paperback editions have sold 22,554 copies over the same period. (BookScan tracks most, but not all, physical book sales in the U.S. and often lags by a week or more, which means that the actual numbers are almost certainly greater.)

For Hachette, this could mean a significant loss of revenue and for HarperCollins, which published Go Set a Watchman and is now the only publisher that can claim Harper Lee as an author, it almost certainly means an increase in Lee-related revenue.

That said, mass-market paperbacks have been on a precipitous decline lately, though TKAM’s success, particularly in the education market, makes it a notable exception. But many publishers are moving away from the format. Pressed for further comment, a HarperCollins spokesperson informed me that “Like many American classics, To Kill A Mockingbird’s primary paperback format will be the trade paperback edition.” That’s an important distinction: The general trend in publishing has been against the mass-market and toward more expensive (and durable) editions—many American classics, including The Great Gatsby and The Grapes of Wrath no longer have mass-market editions.

Of course, the book will still be available in any public library in the country, and used copies are available on Amazon for prices as low as 40 cents (plus shipping and handling). But the disappearance of the mass-market edition could have a significant impact on schools. The fact that To Kill a Mockingbird is both so accessible to young readers and so widely taught in America is crucial to its cultural importance. In 1988, the National Council of Teachers of English reported that To Kill a Mockingbird was taught in a whopping 74 percent of schools and that “Only Romeo and Juliet, Macbeth, and Huckleberry Finn were assigned more often.” Today, To Kill a Mockingbird has almost certainly surpassed the controversial Finn as the most assigned novel in America’s middle- and high schools, and those often cash-strapped schools are far more likely to buy the cheaper mass-market edition than the more expensive trade paperback. According to the email sent by Hachette to booksellers, “more than two-thirds of the 30 million copies sold worldwide since publication have been Hachette’s low-priced edition.”

Without a mass-market option, schools will likely be forced to pay higher prices for bulk orders of the trade paperback edition—and given the perilous state of many school budgets, that could very easily lead to it being assigned in fewer schools. (Schools typically receive a bulk sale rate that gives them more than 50 percent off of the list price of a book—they most likely pay less than $4.50 per copy of the mass-market paperback of TKAM, whereas a copy of the trade paperback would cost no more than $7.50.) Hachette is upfront about this possibility: a bullet point in the email reads, “The disappearance of the iconic mass-market edition is very disappointing to us, especially as we understand this could force a difficult situation for schools and teachers with tight budgets who cannot afford the larger, higher priced paperback edition that will remain in the market.”

Although we can’t make any claims with certainty without exact royalty information, traditional publishing economics suggest that Lee’s estate will now receive more money per copy of To Kill a Mockingbird sold under the new arrangement. Mass-market paperbacks typically receive higher royalty rates than trade paperbacks, but often generate lower per sale royalties. As of 2013, standard royalty rates were 7.5 percent on trade paperbacks and 8–10 percent on mass-market books, though Lee’s terms are almost certainly more beneficial than industry averages, given her profile and the consistent level of sales To Kill a Mockingbird generates. In any case, even with a slight-to-moderate decline in sales, the Lee estate stands to make more money in royalties, now that the trade paperback, and not the mass-market edition, will be the cheapest, and therefore best-selling, edition. HarperCollins did not respond when asked for comment on this specific issue.

It’s unclear why Lee’s estate would make a decision that so directly threatens the legacy of To Kill a Mockingbird, by damaging the link between the book and schools, and the email from Hachette offers no answers. The text of one email obtained by the New Republic suggests that the mass-market edition will no longer be published “per the author’s wishes,” while an attached PDF states something slightly different: “As of 4/25/16 there will no longer be a mass-market edition of To Kill a Mockingbird available from any publisher in the U.S. as per the wishes of the author’s estate.” Neither Hachette nor HarperCollins would comment on the Lee estate, and requests for comment sent to both Tonja Carter and her attorney were not returned.

The question of who is making decisions regarding Harper Lee is still a somewhat academic one, as this decision was undoubtedly in the works before Lee’s death on February 19, alongside other changes. On February 10, for instance, Scott Rudin announced he had acquired the rights to produce a Broadway play of To Kill a Mockingbird, suggesting that Lee’s team has continued the flurry of activity that has marked the last few years and looks to continue after her death. The questions surrounding Lee that have emerged over the last few years—namely who is driving changes to her legacy and whose interest those changes serve—also look like they’re here to stay.

What is certain, however, is that Lee’s estate will continue to face publicity problems even as it’s shielded from scrutiny. Without knowledge of why Lee’s estate has radically altered the publication plan of To Kill a Mockingbird, it’s only possible to speculate as to who is pulling the strings—and to what end. This will be true of any decision made by the estate, so long as Lee’s will is sealed. Given the hubbub surrounding Go Set a Watchman, it’s likely that even opening Lee’s will to public scrutiny wouldn’t placate doubters. It’s an unfortunate twist in the legacy of one of America’s most beloved writers. For an author whose reputation in life was rather similar to her character Atticus Finch’s—noble, high-minded, resistant to trouble and chaos—Harper Lee has, in recent years and now, after her death, become one of America’s most controversial writers. It is a striking change in reputation, but one likely to be permanent if the estate continues to operate in secrecy.

This post has been updated to include licensing information.