Donald Trump’s challenge to the GOP establishment now seems on course to succeed.

As Republicans (and many others) consider what turning the party’s presidential nomination over to a real outsider will likely mean, it’s worth looking back at the last time that happened.

Some will say that it was in 1952, when General Dwight D. Eisenhower defeated Ohio Senator Robert Taft for the nomination at a tense GOP convention.

Eisenhower’s campaign, however, was largely the creation of New York Governor Thomas Dewey, who had run three times before. In so doing, Dewey had built a durable election machine that he placed at Eisenhower’s disposal.

The contemporary equivalent would be the highly unlikely move of vociferous critic and GOP establishment stalwart Mitt Romney putting his presidential campaign staff to work on Trump’s behalf.

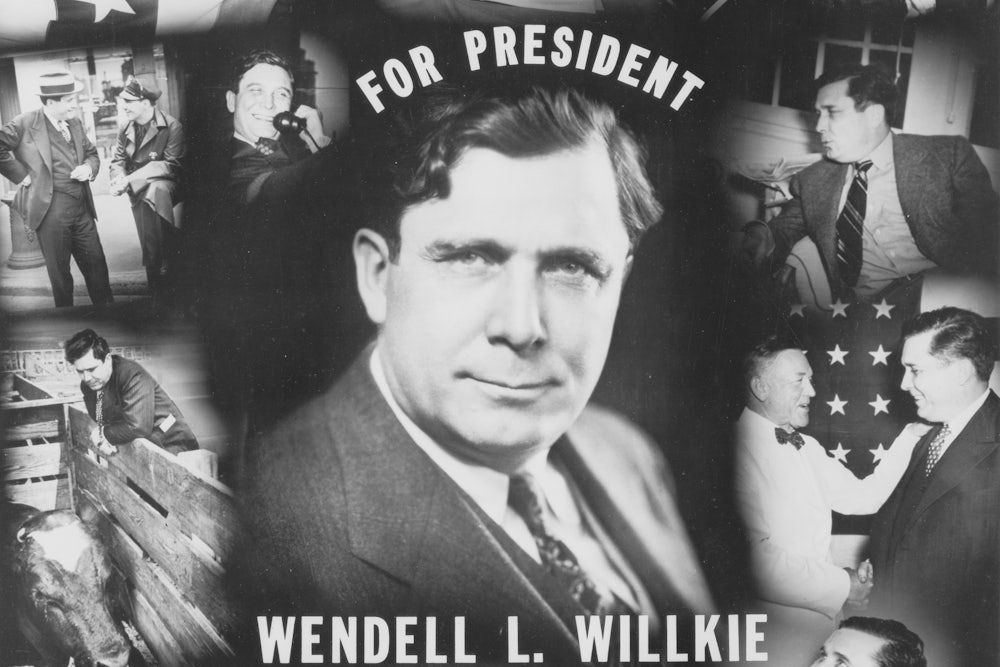

I would argue that to find the last time a genuinely anti-establishment outsider won the GOP nomination one needs to look back even further, to 1940, when Wendell Willkie surprised politicians and pundits alike by doing just that.

So what insights does the Willkie experience offer to today’s politics?

Masterful use of the media

Like Donald Trump, Wendell Willkie was a former Democrat, who reregistered as a Republican only later in life. Like Trump, he came to politics from the corporate world and an office in Manhattan. And also like Trump, Willkie came to national prominence through his skillful use of the national media.

In Willkie’s case, he did that first by writing articles in national magazines attacking President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal for excessive spending and concentrating too much power in the federal government.

He also made his case in a different way, through testifying in Congress.

Willkie was a utility executive, the president of Commonwealth and Southern, one of the largest electricity producers in the country. He became the public face of the big business’s opposition to the Tennessee Valley Authority, one of the New Deal’s single largest projects that would transform a poor agrarian region of the South through the building of hydroelectric dams, flood control and economic development.

As New York Post columnist Cal Tinney wrote, tongue-in-cheek, in 1939:

What are you going to Washington for Mr Willkie? “Oh to see that my contempt for the New Deal remains founded on familiarity.”

Widely covered in the press, Willkie came across as a common-sense critic of the New Deal as something that could and sometimes did go too far.

Next came a triumph in the broadcast entertainment media, in another parallel to Donald Trump’s role on his Apprentice TV show.

The broadcast medium in Willkie’s day was, of course, radio, and Willkie turned in a remarkably strong performance on a radio show called Information, Please, the closest contemporary equivalent to which would probably be Jeopardy. Willkie came across there as quick-witted, knowledgeable, and graceful under pressure.

Anti-establishment

What prompted such an unlikely candidate to run for the GOP presidential nomination in 1940 was Willkie’s sense that the establishment candidates had staked out the wrong stands on the key issues.

The leading inside contenders that year were the “racket busting” Manhattan District Attorney Thomas E. Dewey and “Mr. Republican,” Robert A. Taft, the Ohio senator and son of a previous president.

On foreign policy, both insiders sounded like isolationists. They had expected France to stand fast against German aggression in 1940, as France had in World War I, and they tended to think that the right thing to do was for the U.S. to stay out of Europe’s conflict.

Willkie firmly disagreed.

In terms of domestic policy, both Dewey and Taft struck Willkie as too hostile to the New Deal programs and policies that Willkie did approve of and that were, critically, popular with the public. These most notably included Social Security, the Wagner Act (which protected labor unions), farm price supports, and federal aid to the unemployed.

Willkie’s argument was that the basic ideas behind these programs and policies were sound, but could be more honestly and efficiently carried out by Republicans, who would rely on state governments more and Washington less in doing so.

A tense GOP convention

To the amazement and consternation of GOP regulars, the Willkie campaign caught fire in May and June of 1940.

The rapid military collapse of France exposed the shallowness of Dewey’s and Taft’s grasp of national security issues. And their excessively partisan attacks on the New Deal did not—as measured by George Gallup’s polls—have broad appeal.

By the time the GOP convention opened in Philadelphia in late June, about 30 percent of Republicans surveyed said they favored Willkie. That together with the lack of a united front among the establishment candidates opened the door to a thoroughly unexpected Willkie triumph on the sixth ballot.

So angry were establishment Republicans at this turn of events that Willkie was obliged to give only a very short and vague acceptance address, lest he alienate even more the party leaders who had strongly opposed his candidacy.

Seventy-six years on

The parallels to today are easy to see.

Whatever one thinks of the stands Donald Trump has taken on the issues, they have resonated strongly with a large enough fraction of the GOP primary and caucus electorate to make him the presumptive nominee. Establishment candidates are not united, and GOP orthodoxy has proved to have too little appeal.

Like Willkie, Trump has run as an insurgent populist, challenging the elitist wing of the GOP that has long dominated the nominating process.

And like Willkie, Trump will find winning enthusiastic support from Republicans who supported establishment candidates very difficult, because they denounced him as an unqualified interloper during the primaries and caucuses.

Neither the Willkie nor the Trump candidacies has destroyed the GOP, but both disrupted it. The consequences were lasting 76 years ago, and I would predict they will be so this time around also.

In Willkie’s case, his nomination helped reorient the GOP away from a strongly anti-New Deal position to one that accommodated the most popular New Deal stands on matters foreign and domestic, such as support for Social Security and aid to Britain during World War II.

Trump appears to be doing something similar, in the sense that his nomination will likely push the GOP to do more to improve life for working- and lower-middle-class Americans, who have seen their quality of life decline in important ways over the past generation.

FDR’s wartime envoy

What is most troubling, however, about the Trump phenomenon thus far is how different he sounds from Willkie on issues of racial discrimination.

Wendell Willkie sharply criticized the segregation of his era. “No man,“ he said, “has the right in America to treat any other man ‘tolerantly’—for tolerance is the assumption of superiority. Our liberties are the equal rights of every citizen.”

To make that point plain, he became the first major party candidate to campaign in Harlem since it had become a predominantly black neighborhood.

African American Joe Louis, the great boxer, was the warm-up speaker for Willkie’s two appearances there, where he received a friendly welcome.

Even though Willkie ultimately lost Harlem and the election of 1940 to FDR in a landslide (82 electoral votes to 49), Willkie’s campaign helped change the politics of his day, by pushing the GOP toward an accommodation of Roosvelt’s policies.

FDR even made Willkie a spokesman for America abroad after the election, a signal of the two parties coming closer together as a result of Willkie’s unorthodox bid for the presidency.

Reconciliation can and does follow confrontation. Not a bad lesson to remember as we watch the fireworks of the 2016 election campaign.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.