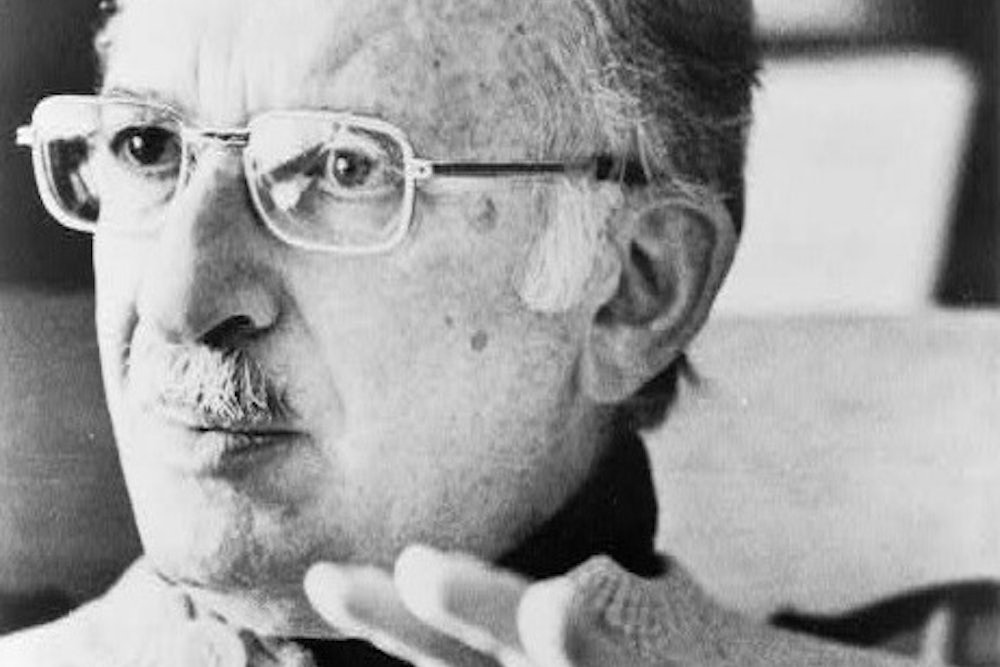

The Times headline reads: “Bernard Malamud is Dead at 71. Author Depicted Human Struggle.” Well, yes, I think, after recovering from the shock and starting to feel the sorrow, he did do that. But don’t all writers do it in one way or another? Isn’t there a depiction of human struggle even in those books that don’t make it their theme or subject, even in those “inhuman” works (as Robbe-Grillet’s novels were called) that are more concerned with the nature of language or perception than with lives? To write at all, to set down words in formal ways, to imagine fictively, is to report on a struggle. Malamud did that, more directly than most.

But what kind of a writer was he? Rilke spoke of fame as “the sum of misunderstandings that has gathered around a person.” Malamud was known for having had “compassion,” “moral wisdom,” a concern for the “ordinary man.” True, but was that what made him a good writer? The misunderstanding in his case lies in how the relation between those virtues and writing itself is seen.

If anything, what we might call the humanistic values of his writing gave him an air of being a little out of date—earnest, kindly, thoughtful. His gaze was on the perennial, instead of conjuring with our confusions and chaos and inventing brilliantly in order to confront and combat them. He was a storyteller in an era when most of our best writers have been suspicious of straightforward narrative. Nobody thinks of him as an innovator, unless being among the first to bring the rhythms and intonations of Jewish, or Yiddish, speech to formal prose counts as innovation.

He himself contributed to the image of a somewhat old-fashioned, or unfashionable, champion of the spirit, a humanist in a literary era in which humanism is almost anomalous. Again and again he used the word “human” in the occasional interviews and speeches he gave: “My work ... is an idea of dedication to the human. ... If you don’t respect man, you cannot respect my work. I’m in defense of the human.” And he spoke of art as “sanctifying human life and freedom.”

So what’s to object, as he might have put it? Those lofty, sonorous phrases, more mottoes than anything else, left me uncomfortable when they came from him and leave me so when they come from others. It isn’t enough to speak of defending the human or respecting man, or rather it sounds a bit self-serving and even pompous. Did he think it was what was expected of him? To shift the burden to us, isn’t it naive to say that he “touched our hearts”? Bad fiction, melodramas, kitsch touch our hearts too, bring tears more reliably, certainly in greater floods, than does good writing.

It seems to me that Malamud was usually at his weakest when he sought or fell into too direct a way to our emotions, when he was most self-consciously “humane.” I think of stories like “Black Is My Favorite Color,” “The Lady of the Lake,” and “The Loan,” each brought down by predictable sentiment, and even more of novels such as The Fixer, at once heavy, pseudo-lyrical, and tendentious; The Tenants, where social painfulness isn’t fully transmuted into imaginative truth; and God’s Grace, embarrassingly cute in a mode of fantasy—jocose, biblically flavored science fiction—to which he wasn’t suited.

To what, then, was he suited? To begin with, there is that swift rooting of so many of his protagonists in an occupation or a past. His opening words located his characters: “S. Levin, formerly a drunkard”; “Davidov, the census-taker”; “Manischevitz, a tailor”; “Fidelman, a self-confessed failure as a painter”; “Kessler, formerly an egg-candler.” Having so placed them, relieved of the necessity to develop them, yet having granted them a specificity that kept them from being parabolic, he moved them quickly into position to experience their fates. These are destinies of self-recognition—ironic, painful, lugubrious, or threnodic—and they are, when all is working well, revelatory of the morally or psychically unknown, or not yet known. And along the way, there are the pleasures of the text, the little fates of language:

From Idiots First: “He drew on his cold embittered clothing.”

From “The Magic Barrel”: “Life, despite their frantic yoohooings, had passed them by.”

From “The Girl of my Dreams”: “... he pitied her, her daughter, the world. Who not?”

From “The Death of Me”: “His heart, like a fragile pitcher, toppled from the shelf and bump bumped down the stairs, cracking at the bottom.”

From “The Jewbird”: “The window was open so the skinny bird flew in. Flappity-flap with its frazzled black wings. That’s how it goes. It’s open, you’re in. Closed, you’re out, and that’s your fate.”

From Dublin’s Lives: “On the road a jogger trotted toward him, a man with a blue band around his head. He slowed down as Dublin halted. ‘What are you running for?’ the biographer asked him. ‘All I can’t stand to do. What about you?’ ‘Broken heart, I think.’ ‘Ah, too bad about that.’ They trotted in opposite directions.”

From somewhere: “exaltation went where exaltation goes.”

He was neither a realist nor a fantasist. He was both. I don’t mean he alternated between reality and fantasy, but that at his best the line between the two was obliterated. Observation gave way to imagining. Without strain, experience flowed into dream. In some stories characters and properties literally move up into the air, as in Chagall, with whose paintings these tales have been justly compared. “He heard an odd noise, as though of a whirring of wings, and when he strained for a wider view, could have sworn he saw a dark figure borne aloft on a pair of magnificent black wings” (“Angel Levine”). “He pictured, in her, his own redemption. Violins and lit candles revolved in the sky” (“The Magic Barrel”). Even a story like “The Jewbird” (to my mind perhaps his finest), a piece that appears all whimsy and allegorical effort, is anchored in pebbly actuality, an actuality into which the bird flies, scattering meanings as he does feathers, an agent of our own self-knowledge.

In a culture where quantity is god it may seem demeaning to say that Bernard Malamud was a better short-story writer than novelist. Yet a case can be made that many great or good writers of fiction in English have been better makers of stories than of novels: Hawthorn to go way back, Lawrence, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Cheever, Flannery O’Connor. She wrote in a letter of 1958 about a short-story writer “who is better than any one of them, including myself. Go to the library [for] a book called The Magic Barrel by Bernard Malamud.” (He was immensely pleased, for he greatly esteemed her.)

To be sure, the novels have their pleasures, but even in the best of them his predilection for the shorter form often shows itself, straining against what novels are supposed to be. Books as good as The Assistant and Dublin’s Lives are, I think, more notable in some ways for their nearly self-contained sequences than for their architectonics and narrative continuity. He may have called Pictures of Fidelman an “Exhibition” because he saw that it would otherwise be taken for a novel (it was by most anyway) and faulted for its lack of development. It wasn’t easy for him to follow a fiction through a long, complicated course to its end. His wish for those qualities of epiphany, of revelation and decisive verbal triumph, kept breaking through.

What makes his place in literature and our memories secure isn’t his themes or subjects. It isn’t his nobility of purpose, his compassion or moral understanding, in short, his humanism. Or rather it’s not those qualities in themselves, as detached and detachable essences. One wants to say to the sentimental admirers of his fiction (as well as to those erstwhile admirers who found him growing “cold” in his later work) that imaginative writing isn’t the exemplification of preexisting values and virtues. It is their discovery, against all odds, in the shocks and surprises of the unfolding tale. The imagination teaches us newly. It doesn’t instruct us in what we already know, and it certainly doesn’t grant us our comfortable, “humane” wishes.

“It’s not easy to be moral,” thinks Cronin, the protagonist of “A Choice of Profession.” It’s at least as difficult to shed moral light in fiction, where the recalcitrance of words, their pressure toward the familiar—and hence the unenlightening—is constant and unyielding. “Creativity,” Arthur Koestler wrote, “is the defeat of habit by originality.” Habit was for Bernard Malamud, as for all true writers, the enemy from which you wrest the victories you can, replacing, through a series of miracles, the banalities or weariness of language with its grace.