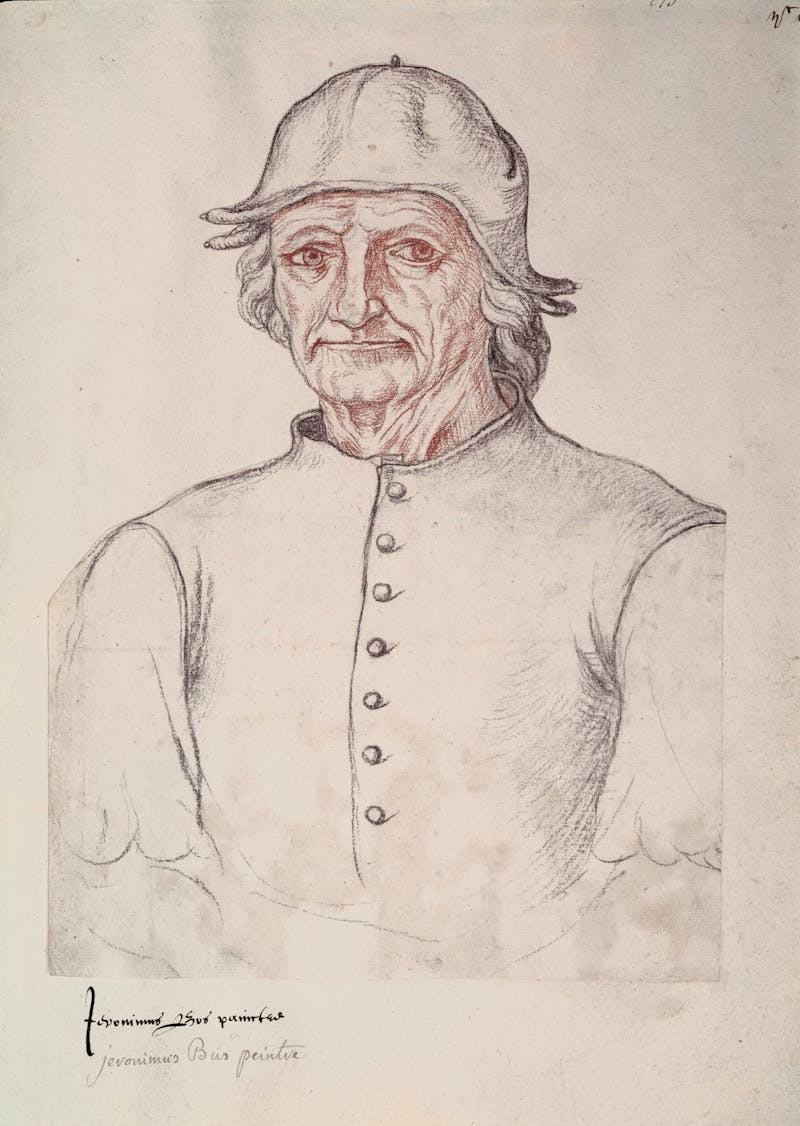

Hieronymus Bosch, elusive conjurer of jewel-like panoramas in which elegantly rendered humans, birds, fish, fruits, insects, musical instruments, and odd machines co-mingle, cavort, and run amuck in orgies of seemingly lewd and brutal communion, died on August 9, 1516, making this year his quincentenary. Bosch’s unknown birthdate hovers, by scholarly consensus, around 1450, but we do know for certain that he came from a family of painters surnamed van Aken and that he lived and worked all his life in an atelier still standing on the market square of a medieval town called ‘s-Hertogenbosch in the Netherlands, now an hour or so by rail from Amsterdam. To honor this favorite son, the town has proclaimed a year of revelry. The Bosch-themed events, theatrical and otherwise, are spearheaded by a unique exhibition of his art at the Noordbrabants Museum, which stands just a few blocks away from the attached three-story ungabled house in which Bosch is said to have dwelt with his childless wife Aleid van de Meervenne.

Titled “Jheronimus Bosch: Visions of a Genius,” the show claims to bring together more of Bosch’s works than have ever been seen under one roof: 17 out of his 24 paintings and 19 of his drawings. (Since attributions shift year to year, however, it might be prudent to regard the authorship of the paintings, rather like the figures they portray, as being in a state of flux.) Early in March, I flew to the Netherlands just to see it, as Bosch has been an obsession of mine since childhood. Like many of my peers, my first exposure to his shape-shifting, spell-binding world came in the form of glossy reproductions, color plates in massive art books. Our family’s volumes weighted down the bottom shelves of mahogany bookcases in front of which I sprawled poring over details—tiny details that rewarded hours of staring. Painted in sure strokes with small brushes, sometimes not more than a single hair, and brilliant hues, Bosch’s teeming human-scapes exuded an aura of the forbidden to my child’s eye. Even at their most dire (the Hell and Last Judgment panels of the triptychs), they were never as frightening to me as images by Bosch’s contemporaries, those, say, of the German painter, Matthias Grünewald, whose bleeding, tortured, twisted-fingered Christ on the central panel of the Isenheim Altarpiece struck terror. Bosch, by contrast, induced queasiness but even more compellingly, wonder. Bosch can be eerie, nasty, playful, but also beautiful.

Unfortunately, the curators of the Netherlands exhibit have eschewed all engagement with ambiguity. (There is, however, one passing mention of the word ambiguous in a brochure description of the so-called “Peddler” or “Wayfarer,” a figure repeatedly painted by Bosch and formerly called the “Prodigal Son.”) They have chosen to contend that Bosch, a faithful Catholic, was exclusively a religious moralist with a single idea to convey, namely that: Mankind is struggling for good in a world of evil. Through printed matter and an audio guide, the local exhibitors drum this message into the ears of thousands of spectators who are flocking daily to the exhibition mainly, as it appears so far, from other parts of Europe.

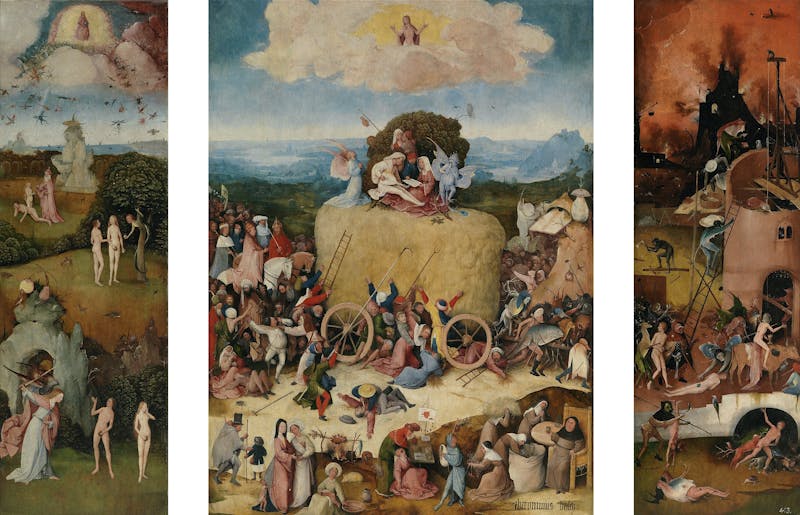

Borrowed from far-flung collections in other parts of the Netherlands, Europe, and the United States, the paintings themselves are a feast for the eye. Hung in under-illuminated halls for protection, they gleam in the surrounding darkness, as do several monitors displaying framed video loops of details from the exhibited works. While “The Garden of Earthly Delights,” which is currently housed at the Museo del Prado in Spain, is not included in the exhibition, one can see a near-contemporary copy of its central panel, as well as “The Haywain,” “The Wayfarer,” “St. John on Patmos” and “St. John the Baptist in the Wilderness,” “The Ship of Fools,” “The Temptation of St. Anthony,” among other painted works, and intricate pen and ink drawings of beggars and monsters. Divided into six themed galleries, from “The Pilgrimage of Life” to “The End Times,” the museum’s overall presentation gives priority to identifying the works’ religious themes, to new techniques of art examination and restoration, and to local influence. Visitors puzzled by content and curious about meaning will leave with their bewilderment intact.

It is a pity that the curators take this approach, for if Bosch is really the “genius” they herald him as being, he is so precisely because he transcends the parochial. Five centuries of fascinated viewers have not been riveted by Bosch merely because of religious orthodoxy. Think of his admirers among the Surrealists, Leonora Carrington, for one, or the modern dance choreographer Martha Clarke, or the brilliant fashion designer Alexander McQueen. Bosch’s appeal extends way beyond dogma, capturing ordinary viewers who may be spectacularly ignorant of, or indifferent to, it. The enthusiasm his work has drawn down the centuries has hardly been for the sake of its piety.

Why, for example, contra the argument of the current show, was Bosch periodically said to have been a closet heretic rather than a faithful Catholic? This was notoriously alleged by William Fraenger in 1947, and refuted, but suspicions have arisen periodically, recently in a highly questionable book by Lynda Harris. What is it about his art that gives this notion even a moment’s credence? How could anyone have thought Bosch a heretic when it is well-documented that from 1495 to 1501 he belonged to the Illustrious Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady, a religious confraternity openly hostile to dissenters, and whose brethren said masses for him when he died, and when we know further that, after his death, his art was collected and prized by the allegedly pious Philip II of Spain, a monarch associated with the Counter-Reformation? Something inherent in Bosch’s work apparently prompts those recurrent suspicions far-fetched though they may be, and that something deserves to be interrogated rather than dismissed out of hand.

With his fecund strategies of visual rhetoric, Bosch plunges us into ambiguity. With all his transgressions of boundaries among species and scale, he is surely daring on some level to intimate that the scope of our moral universe cannot be bifurcated except superficially. Evil penetrates good and vice-versa. Predators roam, for example, in Paradise on the left panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights. And, if this be so and if classifications blend, then the binary categories themselves might bear re-visioning. Bosch stops before going there. We, however, need not.

As we linger and gaze, his work does not grow simpler, nor easier. St. John the Baptist naps unconcernedly in the wilderness; the little white lamb toward whom he desultorily gestures looks away. Meanwhile, an eerie, vile-looking spiny plant spills its seeds, pecked at by birds, and, rising up to bisect the saint’s body, it divides him in two with its thorny tentacles. Reading Bosch’s imagery beyond the conventional Christian iconography that inheres in it and grounds it, his art grows ever more layered, nuanced, and evocative of the metamorphic ways of being in the world that most of us try to avoid when we want to “be good.” In reminding us of that, and in stimulating fantasies in us and dreams and nightmares we have either put aside or never imagined at all, Bosch transcends his origins in town, century, and creed. And why should this be strange for an eccentric painter whose artistic process breaches all boundaries of animate and inanimate and reaches beyond time-worn categories of animal, vegetable, and mineral, and whose technique itself is a marvel of innovative luminosity? For this, we travel across the world. With his unreality, Bosch gives us what is truly real.

A long list of distinguished academics (including but in no special order Charles de Tolnay, Dirk Bax, Ludwig von Baldass, Laurinda Dixon, Jacques Combe, Walter Gibson) have devoted reams of scholarship to tracing the sources of Bosch’s arcane inventions. Oft cited are manuscript illuminations, bestiaries, local Netherlandish history, scenery, folklore, and proverbs, variations on conventional Christian iconography, astrology, alchemy, hermetic practices, even Tantrism; yet, the psychological aspects of his work with respect to its viewers over time have garnered scant notice.

Bosch uses, I wish to suggest, a host of effective visual techniques to mitigate strong emotion; thus, it is not precisely terror of damnation per se, or evil, or wickedness itself to which we are privy, but rather a kind of free-associative chain of vignettes that never blindside us but remain conspicuously open and available to our interpretation. As a child, I felt this, and I see it still: the sexual and violent acts performed by these swarming masses of humans and quasi-humans upon one another are always taking place somewhere else, far away, in distant realms, and distance offers protection. Look also at how delicate, slender, even fragile, and almost ubiquitously hairless the bodies are, whether white or occasionally black. Their tapered feet and fingers might belong to dolls or manikins, rather than to potent, fleshly, lustful adults. Whereas their nudity embarrassed me as a child, it now seems more tender than lascivious.

Are these figures villains? Notice the vacuity of every face, which drains emotion from even the most sadistic acts. Does anyone in these little cameos, victim or perpetrator (categories not always kept apart in true Boschian style) actually care? Think, in the right panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights, of the armored helmeted knight with a golden goblet, out of which a white ball has rolled whose bloody body has already been half-eaten by six lizard-dogs, three green and the others gray; he shows no feeling of any kind. Should we? There is an insouciance as if a pageant were occurring: marionettes arranged by an invisible director on a richly appointed stage. Always two-dimensional. Bosch gives us occasional depth, but mostly we remain on the surface of the picture plane, and this too keeps us from being pulled in.

Rarely do we descry a cruel grimace or leer, nor even two figures making direct eye contact with one another. The two works in which we do glimpse emotion are Christ Carrying the Cross from Ghent, which was recently excised from the Bosch canon and re-dated to after his death, and the Valencia Passion Triptych, similarly attributed to a follower of the artist, not Bosch himself. Surely, our reactions are tempered by this emotional absence on the part of the participants pictured in Bosch’s works. How different from the pathos of that other early Netherlandish artist, Rogier van der Weyden, whose work cannot help but elicit tears of compassion.

Peculiar postures, such as can be seen in The Garden of Earthly Delights, the man bending over to reveal a duet of posies emerging from his rear end, or the fellow inside a blue sphere waiting for a great duck to pop a cherry into his open mouth, or another fellow caressing an impassive blonde inside a crystal while an adjacent male, his entire upper body submerged, ambiguously protects or reveals his genitals seem sites of whimsy and eccentric invention rather than iniquity. Even the sadism of Hell (those huge ears pierced by an arrow with a blade emerging between them and a figure being impaled on the strings of a harp) is softened by our wonder at its sheer inventiveness and because we are not invited in but kept at a psychologically safe, thoughtful distance.

In college, hoping to find helpful answers about Bosch, I studied with art historian Julius Held, who assigned the legendary Erwin Panofsky’s two volume work on Early Netherlandish painting. One gloomy afternoon in Columbia’s Schermerhorn Library, I fell upon the following passage:

No survey of Early Netherlandish Painting can be complete without a discussion of Jerome Bosch. Such a discussion, however, is not only beyond the scope of this volume, but also, I am afraid, beyond the capacity of its author. Lonely and inaccessible, the work of Bosch is an island in the stream of that tradition the origins and character of which I have endeavored to describe. His technical procedure is unique as are the operations of his mind…

My dismay came sharp and swift, like the arrow that cuts into those giant ears in The Garden of Earthly Delights. Panofsky would teach me nothing about Bosch, but in that moment of betrayal, I discovered the humility of a truly great scholar.

Obviously, the impact of works of art alters from age to age, and one wants very much to re-imagine its initial reception, despite the 500 years. What matters at least equally, it seems to me, is the endurance of these visions. Beyond their remoteness and delicacy, which push us toward cognition rather than emotion, there is the aesthetics of Bosch’s painting itself and its heady effect on its viewers. Bosch is less a master of composition than a master of draughtsmanship, color, and light. Think of the right “Hell” panel of Bosch’s Haywain triptych: those dazzling bits of white paint that edge the figures, done with the tiniest of brushes, and the cast shadows, the exquisite sense of line—all the tails and beaks, a snake that is just a sinuous black-gray form edged in shining white and the miniscule dot-like teeth of the dog biting a fleeing man. We cannot help but revel in the rusts and orangey pinks of fiery perdition with its coal-black building burning on high, almost like a one-eyed ebony giant. Whether or not Bosch was channeling here a terrible fire that wracked the town, the glory of his painting lends the scene a savage beauty.

As I imagine him at work, Bosch calls forth these marvels in an artistic process that alternates slow with rapid stokes, bouts of oneiric fervor, during which one part-image implies another that morphs to the next and so on until what he has wrought gels and, in one especially unforgettable moment, a chorus of nondescript souls in Hell appear singing bars of music tattooed on the backside of a naked recumbent man whose occluded face neither Bosch nor the singers nor you nor I will ever see. Panofsky had it right.