“You being ashamed to send your tit pic is misogynistic.” Anna, a high school senior, took a screenshot of the text, which appeared to be sent by someone named Tony. “If you were really a feminist, you would be comfortable showing us your body,” Tony wrote. “Breasts are not sexual body parts. They’re something everyone has. Don’t let your internal misogyny stop you from sending nudes.” Anna tweeted the screenshot under the words “they’re advancing.” As it went viral across social media, the exchange was seen as a shocking but perfect example of how far boys are willing to go to manipulate girls into sending them naked photos.

The text, however, wasn’t real. Anna’s friend had written and sent it to a group chat. I asked Anna if her friends joked about boys demanding nudes because it happened so often. “No guy has realistically asked for nudes to that extent,” she said. “It’s usually a casual ‘do you have Snapchat?’ message on Tinder.” Did the ease with which boys could pursue girls on social media and the internet feel oppressive? Had the pressure to get likes on Instagram hurt her self-esteem? “I can see how that could easily happen, but for me personally social media has never hurt my self-esteem,” Anna told me. “If anything it’s satisfying to watch people like and retweet what you have to say.”

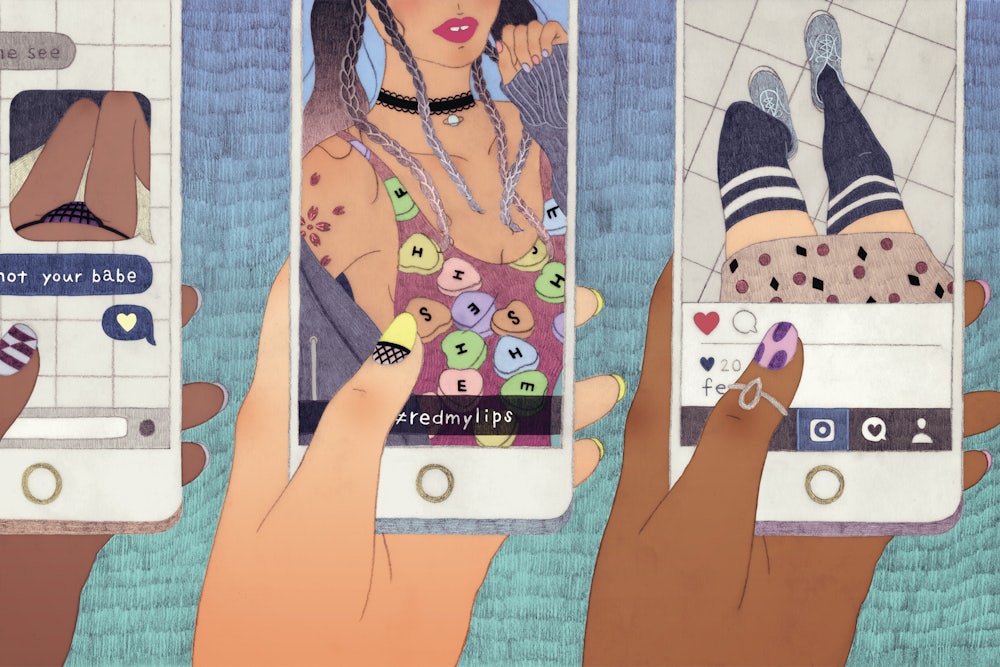

If you take Anna’s text at face value, it encapsulates the bleak picture of contemporary teen-girl life Nancy Jo Sales paints in her new book American Girls: Social Media and the Secret Lives of Teenagers. Sales argues that social media spews two all-consuming messages to teenage girls nearly every moment of every day: Always look pretty, never be prudish or slutty. It’s less the wisdom of the crowd than the sexism of it. Teenage girls feel like contestants in a “never-ending beauty pageant in which they’re forever performing to please the judges” by posting “flawless” selfies. They’ve become “hypersexualized” by the pressures of social media, their self-worth measured in Instagram likes, subjected every day to outrageous demands from porn-obsessed boys who insist they photograph their naked bodies for the fleeting approval of their male classmates. Dating apps increase the sexual availability of girls, which cause “some boys to undervalue the importance of any particular girl, and to treat girls overall with less respect,” Sales writes. The boys demand sex quickly and move on if rebuffed: “So how is a girl who is interested in boys to compete for their attention in this crowded space? It wouldn’t be surprising if some girls thought pictures that are provocative, nudes and semi-nudes, would be one way of getting their attention.”

Sales has written extensively about teenage culture for Vanity Fair, including a 2010 article on the “Bling Ring,” a group of Hollywood teenagers who robbed celebrity mansions. For American Girls she interviewed over 200 teenage girls, their parents, and experts in the field. Sales lets her subjects speak at length. As she’s getting ready for her first date, Lily, a teen from Long Island, riffs on science camp, sibling rivalry, competitive high school sports, the pressure to get into college, the awkwardness of meeting an online friend in real life, the danger of meeting old men online, modeling, America’s Next Top Model, Miley Cyrus, the “media,” fashion, makeup, showing off online, flirting online, and how “everyone wants to be famous.” For Lily, every single one of these things is significant and intense and weird. It should be, because this is all new to her—she’s 14. It’s Sales’s project to prove that something fundamental has changed in teenage culture—in the universal human experience of seeing and communicating with the world for the first time as an independent person. But that’s often the problem with Sales’s argument—she seems to think the human behavior revealed on social media was actually created by it.

The challenge is that for nearly every one of Sales’s anecdotes about the sexual double standard or the prison of beauty, I can think of a similar incident from my high school years, a pre–social media age: There was this one girl who did this risqué thing and then everyone found out about it. What is new is that the internet gives today’s girls easier access to feminist ideas, while social media gives them the power to dissect and make fun of the boys who harass them. Sales highlights the term “fuckboys”—misogynist young men who use social media to demand nudes and treat women poorly—as evidence of the harassment girls receive online, which it is. But the existence of the word itself is also evidence that girls have been analyzing and dismissing this behavior as unacceptable. Having a name for it gives girls power over it: Just another fuckboy.

There’s another word in American Girls I noticed repeated again and again by the author, her experts, her teen girl subjects, and their internet harassers: “attention.” Girls who take provocative selfies, texting or posting them publicly, are “just trying to get attention.” Attention is delivered as both a diagnosis and an indictment. In Sales’s book, it is also something only girls want.

“Some girls wanted attention so bad, it was like they would do anything for it. Anything for the likes,” Sales writes, paraphrasing a girl named Edie. Nina, a teenager, explains how some girls feel when they send nudes to boys privately, and the boys post them publicly: “They act like they like the attention. Some are just like, Oh yeah, I know my body looks good, so I don’t care if everybody sees it.” From a girl named Zoe: “People have become caught up in how much attention they’re getting, and it doesn’t have to be good attention—it can be bad attention, but it feels like girls have become more absorbed with getting attention through these networks for some reason.” Zoe continues: “We’re trying to clone ourselves in a certain way, and some girls figure, Oh, by showing my ass on Facebook I’m getting attention; I’m getting talked about, people are noticing me, and in some way that’s good.” A 17-year-old from Florida explains that in her state, “there’s a lot of skin exposed all the time, and there’s always an excuse for girls to show off their bodies. That’s when they get the most attention from boys, when they get the most likes.” “There’s no feminism anymore,” bemoans a Manhattan mom. “Men treat all women like whores, and the girls are all willing sluts that will do anything to get something from these monsters.” Sales quotes a troll on a kidnapping victim’s Ask.fm account: “Your not hot shit … and your annoying when you just try to get attention all the time.”

Why is it bad that teenage girls want attention? American Girls does not say. I think it’s shorthand for a whole set of sexist assumptions: Women should be unassuming and humble, they should not be ambitious, and they definitely should not seek out acknowledgment and praise from others. (“You don’t know you’re beautiful,” declared the boy band One Direction in one of many condescending song lyrics in which young men bestow their attention on women like a precious gift.) You don’t hear people say of teenage boys who do dumb or dangerous things to make YouTube videos, “Look at that boy, he’s just trying to get attention.” Teenage boy hair is just as fraught as teenage girl hair. Why do boys skateboard, wear sunglasses, drive too fast, or jump from dangerous heights? To get girls’ attention. When boys do this, it’s charming; when girls do it, it’s corrosive. Men are supposed to strive, women are supposed to be discovered; men are expected to seek the admiration of their peers, be entrepreneurial and adventurous; women are expected to do all the required reading and homework and hope someday someone notices their diligent competence.

There is a tendency to police women for inauthentic behavior deemed detrimental to the sisterhood. There’s the “cool girl” rant from Gone Girl, which rails against women who pretend to like football, dirty jokes, and chili dogs while staying thin and beautiful: “Men actually think this girl exists. Maybe they’re fooled because so many women are willing to pretend to be this girl.” There are “fake geek girls,” attractive women thought to be faking a love of comics and video games in order to, you guessed it, get attention. There’s an Instagram account that posts collected photos of attractive women eating fattening foods called You Did Not Eat That—it has 132,000 followers. Let’s imagine the worst-case scenario inner monologue for these ladies: Dear god I hate football and cheese but this is so worth it for the attention. So what? Everyone wants attention—from the fleeting acknowledgment of mere existence to the aching desire to be known, loved, and remembered after you’re gone.

I asked Anna what she thought about this. “I don’t think it’s bad to want attention, everyone wants attention. I’m not sure why it’s so frowned upon, but it definitely is,” she said. I pointed to the jokes kids shared on social media—couldn’t you also get attention for other stuff? “Yes, getting attention can totally mean getting recognition for your ideas,” she said. “A lot of the time people are shamed for selfies because they’re used for attention, but no one really ever shames someone for sharing a joke. Both get attention, and both are possibly only shared in hopes of getting attention, but only one of them is really shamed.”

When I was ten, my friend and I dug through bins at her parents’ yard sale and tried on old high heels with short-shorts and bright coral lipstick. Her brother scoffed: “You look like hookers.” I remember outwardly acting annoyed but inside thinking yes! Children don’t understand the subtle signals of adult sexuality. Sales is puzzled by fights over dress codes across the country—some girls say bans on short-shorts are sexist, because it shouldn’t be their responsibility to make sure boys aren’t distracted. She writes, “Girls agree that they are sexualized and objectified by a sexist culture; but when they self-sexualize and self-objectify, some call it feminist; or they reject the notion that there is any self-sexualization or self-objectification going on in their choices, and to suggest as much is called slut-shaming and an example of rape culture.” She cites an American Psychological Association report’s dire warning, “Perhaps the most insidious consequence of self-objectification is that it fragments consciousness.”

Is it possible the stakes are just a little bit lower? When teenage girls post sexy selfies, perhaps they are not necessarily dedicating their lives to “self-objectification”? Adolescence morphs your body into something unfamiliar, something that changes how the world relates to you, even though you’re the same person inside. We all have fun until the novelty wears off—a welcome vacation in which this new body, a body that still doesn’t quite feel like your own, becomes a canvas for a new self.

Sales cites many studies about eating disorders, anxiety, depression, and unhealthy dieting, often linked to girls seeing photos of objectified women, but none of these problems were invented by social media. The worst revelation about social media culture, teen or otherwise, may be the depths of human neediness, the desire for constant affirmation. But the best revelation is the savviness with which these young women analyze it. Sales discusses the case of Essena O’Neill, a popular Instagrammer who one day recaptioned her photos of bikini-clad happiness to say they were staged, an act which ultimately brought O’Neill even more attention. “Even calling out the enterprise of ‘likes’ as a sham gets you likes,” Sales writes. “This speaks not only to the culture of social media but its existence in a broader culture of fame, in which so much focus and value is placed on the self and the promotion of self, on self as a brand.” This is an incredibly pessimistic view. That teens would “like” rants about social media being an illusion is not a symptom of addiction to attention but a sign they are far more sophisticated than we give them credit for.

What Sales fails to understand is the kids are self-aware about their needs, their desires, their pleas for attention, and the absurd give-and-take of nudes and selfies. Take a Tumblr joke written by a teenage boy in June. Headline: “OMG EVERYBODY DO THIS IT’S REALLY FUN.” Underneath, in smaller text: “validate me.” It got 95,301 notes. Another post: “Send me nudes when you get home so i know you’re safe.” 153,021 notes.

Here’s a rant by a teenage girl about how girls are held responsible for boys’ behavior:

straight boys are weak and pathetic, queer girls walk into the ladies changing room and see ten women naked, do they stare? do they say something inappropriate? do they make them uncomfortable? no because they have the common fucking sense to recognize when a situation is sexual and that people deserve the most basic level of respect to not be harassed, yet here we are banning shorts and low cut tops in school because straight boys are weak and pathetic

The girl who wrote this later updated the post:

okay i made this post this morning and it has since had eighty two thousand notes, it’s been featured on reddit, facebook, twitter i’ve been sent multiple death threats and messages that i don’t even want to describe

and i have to apologize

i’ve seen the error of my ways

straight boys are not ‘weak and pathetic’

straight boys are weak, pathetic and fucking annoying

That post has more than 1.2 million

notes. When someone posted it on Reddit, it got more than 100 comments, many of

them mean. But the author has her own community—she doesn’t have to be a

passive victim of bullying.

American Girls proves sexism is still rampant in American culture, and girls suffer serious consequences from it. While social media offers plenty of evidence for this, Sales does not prove it’s the cause. Sales argues teens are “hypersexualized,” but a recent study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows teens are having less sex, and the teen pregnancy rate has plummeted. “Now more than ever, I believe, girls need feminism,” Sales writes in her conclusion. “They’re deeply in need of a set of critical tools with which to evaluate their experiences as girls and young women in the digital age.” But now more than ever, they have it right at their fingertips. They can google “feminism,” send links to their friends, make posts about it, use it to criticize boys’ texts, and let feminism inform their viral meta jokes about nudes. Take the post about “weak and pathetic” straight males. An anonymous person asked the young woman who wrote it, “What’s the sluttiest thing you’ve done?” She responded, “Existing in a culture that punishes women for being sexual.”