Helen Oyeyemi had a dream, recently, that when she sent the manuscript of her next book to her publisher, they replied by offering her £2.5 million not to publish the book. Burn it, throw it away… whatever. They didn’t say, and she didn’t ask them to explain what they objected to. She didn’t need to ask.

When Oyeyemi talked about this dream at Green Apple Books in San Francisco a few weeks ago, she asked her rapt audience if they thought it was a good sign. Everyone said yes. Anything to do with a new book from Helen Oyeyemi is an unequivocally good thing (especially a dream). But the author herself was far less certain. When she was writing White is For Witching, she explained, she had a recurring dream in which two girls threatened and abused her, promising to hurt her if she published it. “And,” she concluded, “everyone hated that book.” Someone in the audience interjected, “But that book is great!” Oyeyemi nodded, but accepted the compliment without retracting her statement: Whether or not the book was great, those two vicious dream-children hated it and her.

This is the relationship between Helen Oyeyemi and her readers in a nutshell. The six books she’s written since she was 18 years old are well-loved; you can find negative reviews, but you have to look for them amidst all the adulation, and her readings are packed with adoring fans. But she also knows how unsettling her books really are, how strange and full of violence and terror, maybe better than even her readers. She takes night-terrors seriously. Dreams are when our minds tell us the things we can’t bear to look at in the clear light of day, stories about the world that our conscious minds have discarded and rejected. Dreams are the return of everything our daytime brain has worked to ignore. Dreams are the uncanny and the forbidden.

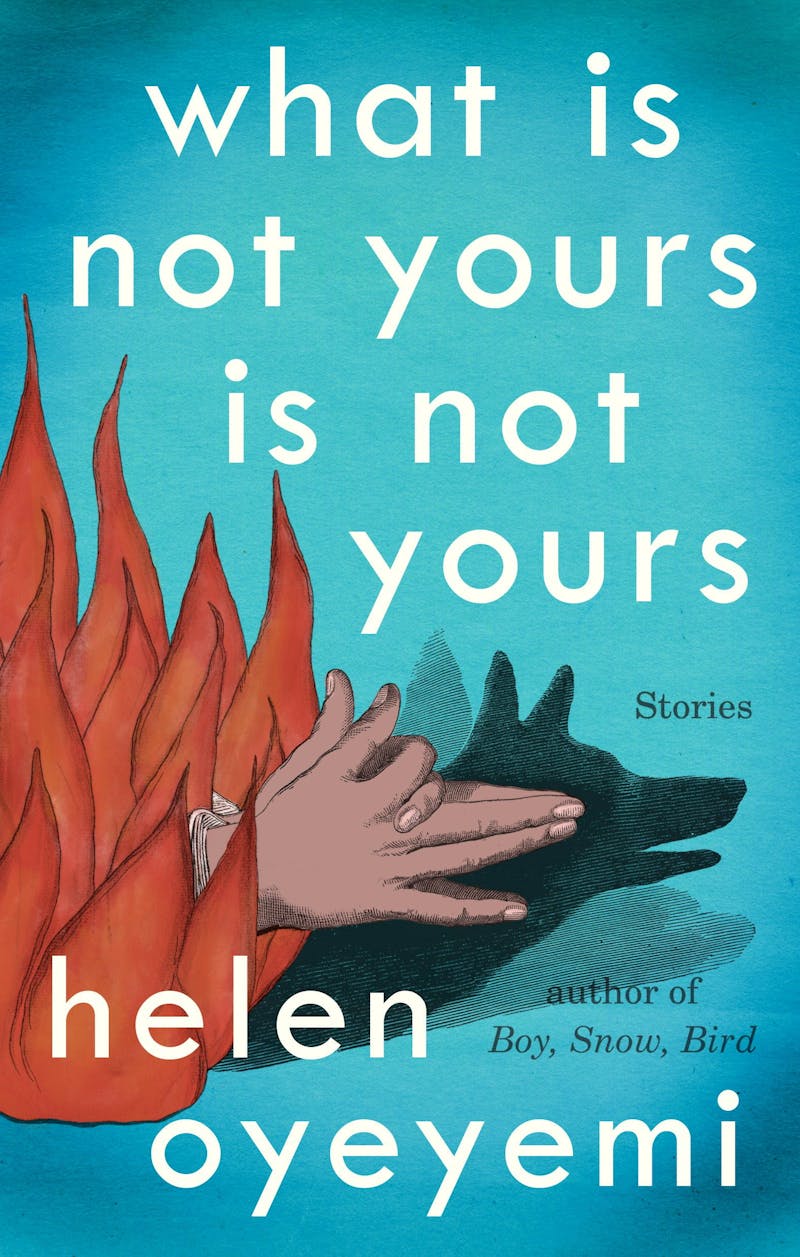

The same could be said of Oyeyemi’s writing. In struggling to describe her work—and it is a struggle—book reviewers often praise her mastery of craft. NPR declared her new novel What is Not Yours is Not Yours “flawless,” a “masterpiece,” and The New York Times describes her as a master author who “expertly melds the everyday, the fantastic and the eternal.” But I would praise her work in almost exactly the opposite terms. Oyeyemi’s fascination is with the flaws that make us human—and the dreams through which we approach our own brokenness—and so, her stories are twisted and imperfect. As another reviewer observed, they are “idiosyncratic in a way that is hard to imagine surviving a workshop setting.” Like dreams, her books are too odd to be good, too terrible to be loved, and too broken to be masterpieces. (In this, she has a lot in common with Silvina Ocampo, and much of Oyeyemi’s introduction to last year’s collection of Ocampo’s fiction could read as a description of her own aesthetic.)

The stories in What is Not Yours is Not Yours are set across Europe—in Prague, Paris, Catalonia, London, Cambridge, and elsewhere—with characters as different and similar as pop stars and students, orphans and step-parents, office workers and hotel handymen. More of them are people of color than not, and most of them are women; all of them are anxiously caught between love, desire, and violence. Sometimes characters from one story wander into another story, but there’s no overarching plot weaving the book together; the narrative leaps from one set-piece to another with the dramatic ease of a dreamer’s wandering mind, beginning and ending wherever they do for no other reason than that’s where they begin, or end. Oyeyemi writes modern fables, fairy tales set in the present. They tell of a house of locked doors that you have to prop open, called “The House of Locks”; a weight-loss clinic where clients sleep away their body-image anxieties; an inventor who’s testing a device that gives you the feeling of a lost lover’s presence.

When Oyeyemi wrote her first novel, The Icarus Girl—a haunting fable about twins separated by the Atlantic, or a Yoruba ghost story set in modern times, or both—she was writing about her heritage, about her family, about the hyphens that made her an Afro-British novelist, or an Anglo-Yoruba writer. So did her second novel, The Opposite House, set in a building with one door that opens in London and another that opens in Lagos. Born in Nigeria in 1984, she grew up in London, but in the decade since her emergence as a teenage literary wunderkind, she’s lived in many cities across Europe—Prague, Paris, Barcelona, Berlin, Budapest—and her work became far less focused on the stories of her own identity than on how stories are the locked doors to any and all identities. Like her third novel, White is For Witching—the story of a racist haunted house in England—and like her fourth, Mr. Fox, What is Not Yours is Not Yours treats the violence of race with a tremendous lightness of touch. If her pages are filled with people of color and women, this doesn’t scan as a “focus,” but a given; why wouldn’t she write about black women?

Oyeyemi began work on What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours, she has said, with the idea of writing nine stories about keys. As she told Vice, she started with a line she remembered from the Hungarian writer Dezsö Kosztolányi’s novel Kornel Esti: “There’s something I must tell you all, and it’s something about keys.” But when she tried to look up the citation, she couldn’t find it, it didn’t appear anywhere in that book. That sentence doesn’t appear in What is Not Yours is Not Yours either, though you could say that it haunts the collection by its absence. The first story Oyeyemi wrote for the collection, “books and roses,” concerns a pair of keys, a pair of lovers, a thief and an orphan, and a garden of roses and library of books. It’s a romantic, novella-length fable, filled with color and suspense, and it resolves with a striking and satisfying neatness: one key opens the door to the library, the other to the adjoining garden, and the two main characters meet in the passageway between.

But “books and roses” is the only story in the book like this, and its neat resolution is more apparent than real. The most uncanny thing about the story, in fact, is the bizarreness of its narrative resolution. After you finish it—after you feel the thrill of the story’s various plots and characters snapping neatly into place—the implausible strangeness of the coincidence hangs in the air like the smell of rotting flowers. Like Chekhov’s loaded gun—in which the playwright puts a gun on stage and it waits to be fired—Oyeyemi’s keys promise a narrative resolution: when they find their lock, we expect, the story will reach its conclusion. But as in life, they seldom do.

Keys are unpredictable: they open up overlapping worlds, stories that open into other stories and take on strange new lives of their own. And sometimes the locks never open. As the final story—called “if a book is locked there’s probably a good reason for that don’t you think”—emphasizes, it might be for the best that they don’t. In the story, a data interpreter comes into possession of a co-worker’s locked diary, but reads it only to learn that secrecy was never the point of the lock. But then what was? We never learn. That lock stays closed.

The longest, most ambitious, and most flawed of the stories, “is your blood as red as this?”, is about a strange school of puppeteering, in which the wooden people appear more living and real than the hands that pull their strings. To be perfectly honest, I found it unreadable until—at Green Apple—she explained what puppets meant to her. In Kenneth Gross’s book about puppets (Puppets: An Essay on Uncanny Life), she read about a master puppet-maker who would make his puppets as perfect as he could, and then smash them, and then repair them. It was brokenness that made them human, she said: A puppet that perfectly resembled the perfect human form would be worrying, even obscene. It was their flaws—and the struggle to live through them—that made them most human. As Gross puts it, “The poetry of the puppet is a poetry of inadequacy, which feeds more fragile, vexed gestures of substitution, revision, replacement.”

These techniques are a good metaphor for how her broken little stories come so devastatingly alive, even while remaining so achingly incomplete. Life offers no resolution, and keys and locks spend most of their time not finding each other. Dreams never come true. But as “if a book is locked…” suggests, there’s probably a good reason for that, don’t you think?