To have “a good cry” brings gentle catharsis, or so I’ve been told. The unburdening of tears is supposed to release pain’s leaden pressure, to cleanse our wounds. And yet crying—the onset, the event, and its aftermath—has been for me a barbed relief at best, and often a panic-stricken necessity. It is an act that must be furtively concealed, the evidence erased.

The experience I describe is not, I think, uncommon, particularly among women. American culture nurtures a robust association between our emotional expression and shame. We’re warned against tearing up in professional settings: at best, to do so is “disruptive”—at worst, “manipulative.” Headlines litter the internet to the tune of “how to cry in public”; vaguely distressed queries read: “Is it ever ok to cry at work? Is it career suicide?” But while an unsubtle tear might compromise a woman’s professionalism, the fault line runs deeper. Manifesting distress too violently and without reservation can render a woman stupefying and grotesque. To put it simply: it can render her ugly.

Over the last few years, we’ve integrated the term “ugly cry” into common parlance, and, in the process, come to rely on it considerably. The concept is straightforward enough: Acceptable as either verb or noun, to “ugly cry” means to weep so fervidly that one’s face contorts in ostensibly unattractive ways. An ugly cry summons expressions that render us strange to ourselves and to others, largely because we’ve relinquished our bodies to wild, emotive energy. We cease to assimilate, to self-curate, and our face mutates into social illegibility.

As a colloquialism, we can trace the ugly cry’s origins to cultural arbiter Oprah Winfrey, who has regularly used the term to describe herself—and her weepier talk-show guests—since at least the year 2000. Meeting Mary Tyler Moore was, according to Oprah, so affecting that she dissolved into “the ugly cry.” She admits to ugly-crying during television interviews and—very understandably—while watching Sense and Sensibility. But this phenomenon, for Oprah, is never welcome. Rather, it results from failed attempts to emote gracefully—to preserve both elegance and mascara. “The ugly cry happens when you’re trying not to cry,” she once said when asked to define it. “And your face goes into all of those contortions, trying not to cry.”

In the last decade, references to ugly crying have trickled

from daytime television into American English. Urban Dictionary contains entries dating

from 2007, but over the last few years the concept has spread at an

exponentially more frequent clip. In February, Perez Hilton scraped

up

“17 Times Kim Kardashian Was In Major Ugly Cry-Face Mode,” and sites like MTV curate

catharsis-focused lists like “5 Heartbreaking Songs To Listen To When You Need

A Good Ugly Cry.” BuzzFeed promises to “make [us] ugly cry” as we watch an

emollient advertisement championing

diversity.

These invitations to weep with abandon assume that readers

will seek solitude before yielding to emotion. When we’re prepared to toss away

our Kleenexes and rejoin society, we can commence damage control—perhaps with

the help of products that notorious ugly crier Kim Kardashian turns to in order

to “recover” from a

weepy episode. (Cosmopolitan’s website, not to be outdone, reassures

us

that a mere eleven steps will abolish any indication of tears.) These websites, of

course, have accurately taken the social pulse. Most of us—at some time or

another—long for the freedom of a “good cry.” We also understand that “a good

cry” is one that occurs where others will not be subjected to its effects. If

that will be impossible, well, perhaps it’s time to research “how to

cry prettily.”

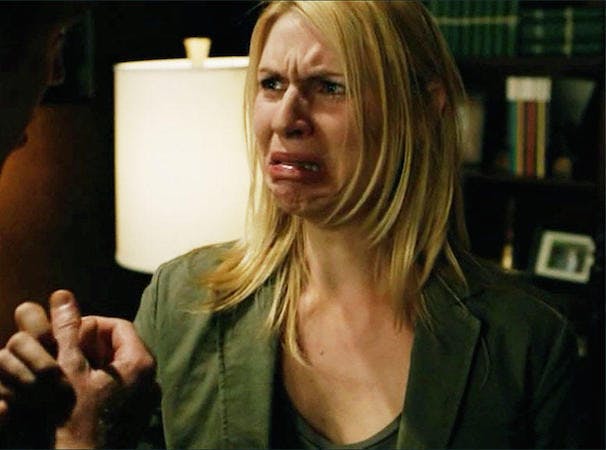

The twinned pressures to perform equanimity and conform to pedestaled notions of female beauty make crying seem more perilous than refreshing. For as often as we find pleasure in Claire Danes’s notoriously unbecoming—if theatrical—cry faces or circulate the meme-ified image of Chrissy Teigen “ugly crying” at the 2014 Golden Globe Awards, most of us would be mortified if we were physically scrutinized at our most vulnerable. If we rely on our arsenal of facial expressions to articulate our competence or our desirability, so too do we call on them for protection. An ugly cry, more than merely being shocking or repellant, conveys our undoing.

Ugliness, after all, is a subjective aesthetic category. When we bashfully admit to ugly crying over a film or a disappointment, we imply that we cannot be beautiful when we give way to our most keenly painful emotions. We imply that untethered grief, by virtue of its excess, does not hew to the cultural expectation that beauty be placid and symmetrical, fundamentally unthreatening. Sometimes the very notion of the ugly cry seems, more than anything else, an inside joke: What woman has not been schooled in the doctrine of Western patriarchal standards of beauty? We know when we have transgressed—when we have become more than men can fathom.

Manifestations of a woman’s acute distress were even more disruptive to Western society in centuries past. In Victorian England especially, society was overtly invested in managing women’s embodied responses, namely those that seemed to transport women beyond the constraints of male-sanctioned decorum. Nineteenth-century physicians turned to the term “hysteria” as a means of medicalizing female behaviors and desires that exceeded precise definition and, thus, social control.

And so, just as the ugly cry was produced by our fear of unrestrained emotion, hysteria, too, was understood as a condition born from excess. Literary critic Andrew Mangham explains that “the Victorian concept of hysteria was heavily influenced by the era’s psychiatric engagements with the idea of immoderation.” Once emotions exceeded a nebulous threshold of normalcy, they metastasized into pathology. “All symptoms of hysteria have their prototype in those vital actions by which grief, terror, disappointment, and other painful emotions and affections are manifested under ordinary circumstances,” nineteenth-century physician Julius Althaus reasoned, “and which become signs of hysteria as soon as they attain a certain degree of intensity” (emphasis mine). The symptoms varied, though Althaus chronicled them as “a feeling of constriction in the epigastrium, oppression on the chest, and palpitations of the heart; a lump seems to rise in her throat and gives a feeling of suffocation; she loses the power over her legs, so that she is for the moment unable to move; and she rings the hands in a spasmodic manner.”

In most cases, female distress was only palatable in its most submissive and delicate variations. In the novel Middlemarch, George Eliot depicts an impulsive and ill-conceived engagement between pampered beauty Rosamond Vincy and the doctor Tertius Lydgate—a romance inspired by the allure of Rosamond’s tears:

“... As he raised his eyes now he saw a certain helpless quivering which touched him quite newly, and made him look at Rosamond with a questioning flash. At this moment she was as natural as she had ever been when she was five years old: she felt that her tears had risen, and it was no use to try to do anything else than let them stay like water on a blue flower or let them fall over her cheeks, even as they would.

That moment of naturalness was the crystallizing feather-touch: it shook flirtation into love.”

Naturalness, as perceived by Lydate—ironically a physician himself—takes shape here in the erotic appeal of a comely young woman’s tearful vulnerability. One can imagine his response had Rosamond’s dainty sniffles intensified into full-bodied weeping (though perhaps his repulsion could have saved the pair a world of misery).

Eliot’s narrative suggests that fetishizing women’s tears can be dangerous, but we’ve seen that fantasy echoed across literature and popular culture. Although the Lady of Shalott in Alfred Lord Tennyson’s poem greets her demise “with a steady stony glance,” British painter John William Waterhouse chose to imagine her with a peaked, porcelain countenance rinsed with elegant suffering. Roy Lichtenstein’s women evince distress in the form of petite, rare tears, their red lips curved fetchingly with sleek eyebrows hardly askew. When, in 1990, Julia Roberts cries at the opera in the appropriately titled Pretty Woman, she glistens softly, a John Singer Sargent painting made flesh. We like our sad girls sexy—and that sexiness can only blossom from tears easily wiped away, not a red face swollen and gooey with snot. Songstress Lana Del Rey has fashioned her identity as a wry acknowledgment of eroticized melancholy: “I’m pretty when I cry,” she breathes on her languid 2014 album Ultraviolence.

These counterpoints to the “ugly cry” are as seductive as they are constraining. They peddle the illusion of emotional freedom without aesthetic compromise; they reify the metric by which we are judged and, sometimes, judge ourselves. “Ugly cry,” after all, is a term used predominately by and for women. We use it to name our transgression—perhaps in good humor, but always with the awareness that we’ve fallen short of a standard we didn’t set. When women are treated as art, we can brush away an errant tear, straighten our blouses, and return to our desks and classrooms and dinners with regality and confidence. No wonder the ugly cry is captivating in its own way: It delivers us from the stranglehold of conventional beauty, asks nothing but that we face our pain.

To cry this way—vigorously, heartily, vulgarly—reveals vulnerability at the same time that it conveys physical might and mettle. Our bodies can speak for themselves, says the ugly cry. Women do not exist merely through representation; we are neither watercolor nor clay. For every time I have shifted uncomfortably as Claire Danes dissolves into tears, I’ve noticed within myself a surge of vicarious pride. I recognize myself, and my agitation in knowing that my own well of emotion is at times too potent and charged for even me to grasp. The hysterical woman’s power—for power she does possess—lies in her refusal to cry inside the lines, and from her dismissal of a westernized emotional doctrine that condemns passion as excess. She is the woman who takes her vibrator to bed not as a Victorian remedy for tempestuous feeling but to scream louder, to dwell in the frisson of sensory ruckus. She knows what I struggle to embrace: that those who would call us ugly for being too freely emotional had better heed our cries and tremble.