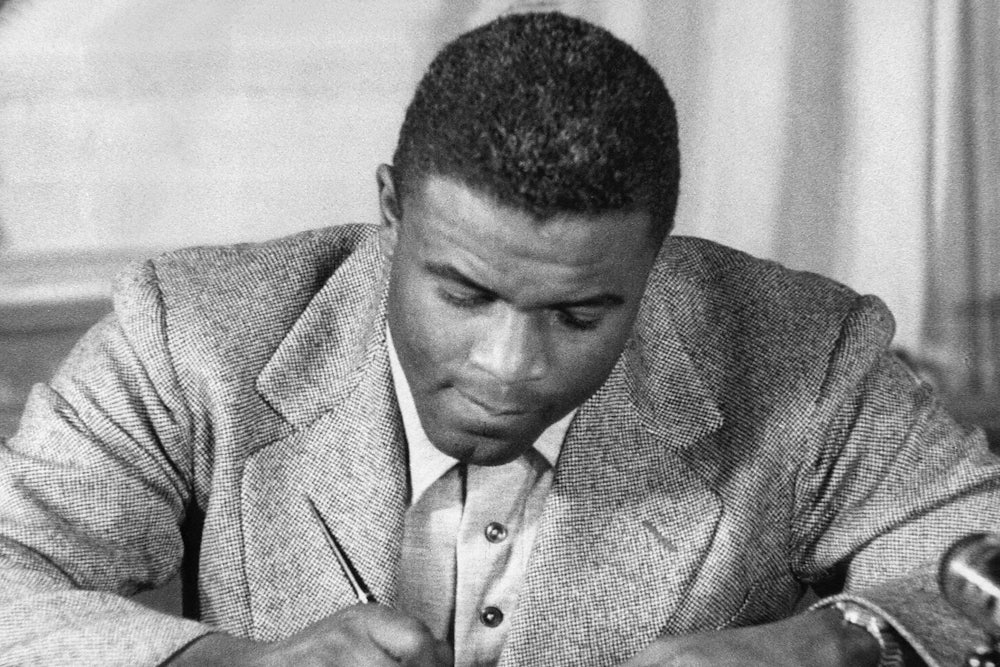

On October 23, 1945, the Brooklyn Dodgers signed Jackie Robinson to their top minor league team, the Montreal Royals, ending the color line in professional baseball.

After the signing, an Associated Press reporter asked Brooklyn team president Branch Rickey if he’d been politically pressured to sign Robinson. Rickey said he had given thought only to Robinson’s ability and the needs of his organization. “No pressure groups had anything to do with it,” he said.

This is the account that was circulated in the days, weeks, years, and decades after the signing of Robinson. It will likely be repeated on Jackie Robinson Day on April 15.

But it wasn’t true.

Rickey certainly deserves credit for confronting his fellow owners and their racist attitudes by signing Robinson and, in doing so, advancing the cause of civil rights.

However, there is more to this story than Rickey and Robinson. In fact, the desegregation of baseball came after a decade-long campaign by black and left wing journalists and activists, which I detail in my book Conspiracy of Silence: Sportswriters and the Long Campaign to Desegregate Baseball.

United around a cause

Beginning in the 1930s, black sportswriters, notably Wendell Smith and Sam Lacy, made baseball part of a larger crusade to confront Jim Crow laws.

Their columns galvanized support among their readers, and their interviews with white major leaguers demonstrated that many players had no objections to playing with blacks.

Black sportswriters, however, had little influence among white politicians and legislators.

This wasn’t the case for white political progressives.

The collapse of America’s economy during the Depression created a hunger for radical politics. The United States Communist Party sought to recruit blacks, in particular, because of the severity of racism in the United States. And communists believed they could win the hearts and minds of black Americans if they could desegregate professional baseball, which had prohibited blacks since the nineteenth century.

The Communist newspaper The Daily Worker, which was published in New York City, began campaigning for integration in baseball shortly after Jesse Owens won four gold medals at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin. Sportswriters for The Daily Worker, including sports editor Lester Rodney, compared the racism in Nazi Germany to the racism in the United States.

During the next decade, the newspaper published hundreds of columns and articles calling for the desegregation of baseball. Its sportswriters excoriated the baseball establishment for perpetuating the color ban and pressured major league owners to give tryouts to black ballplayers.

At the same time, labor unions organized picket lines and petition drives outside major league ballparks, collecting more than a million signatures. In July 1940, the Trade Union Athletic Association organized an “End Jim Crow in Baseball” demonstration at the New York World’s Fair.

The radical left also had friends in New York politics.

Vito Marcantonio, a Brooklyn congressman, called on the U.S. Commerce Department to investigate racial discrimination in major league baseball. Meanwhile, State Senator Charles Perry introduced multiple resolutions in the state Legislature condemning baseball for discriminating against black players.

New York City Councilmen Benjamin Davis, Jr., who represented Harlem, and Peter Cacchione, who represented Brooklyn, called for the city’s three major league teams—the Yankees, Giants and Dodgers—to sign blacks. The Committee to End Jim Crow in Baseball had scores of prominent members and received letters of endorsement from such influential figures as Eleanor Roosevelt and singer, actor and lecturer Paul Robeson.

Rickey seizes the moment

In late 1942, Branch Rickey became president of the Dodgers after serving for two decades as a team executive for the St. Louis Cardinals. Rickey privately told the Dodgers’ board of directors he was interested in signing blacks, even though Rickey knew Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Landis and most, if not all, of the other team owners opposed integration.

In December 1943, Paul Robeson, himself a communist, addressed baseball’s owners, including Rickey, at their annual winter meeting in New York, urging them to integrate their teams. Rickey knew that the communists and other progressives were clamoring for integration but made no attempt to engage them. Rickey biographer Lee Lowenfish called the baseball executive a political conservative who despised communism and labor unions.

But World War II forced many white Americans—especially those who served with black soldiers—to reconsider their views on discrimination. This resulted in anti-discriminatory legislation that helped create the framework for the civil rights movement.

In March 1945, New York Governor Thomas Dewey signed the Quinn-Ives Act, which banned discrimination in hiring and established a committee to investigate complaints.

When Rickey read the news, he responded, “They can’t stop me now.”

In response to Quinn-Ives and to mounting pressure from political progressives, New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia created the Mayor’s Committee to Integrate Baseball. La Guardia appointed Rickey to the committee.

In early August, the Committee to End Jim Crow in Baseball announced it would organize a march to support the integration of baseball. Thousands were expected to demonstrate outside the city’s major league ballparks. The march was canceled after La Guardia assured the committee he was committed to resolving the issue before leaving office at the end of the year.

Later that month, Rickey secretly met with Jackie Robinson and signed him to a contract. Rickey did not want to make the news public until he signed a number of other players from the Negro leagues. In early October, however, La Guardia told Rickey he was going to discuss his committee’s progress in his next radio address.

This forced Rickey’s hand.

Rickey asked the mayor to delay the speech because he had an announcement of his own; Rickey did not want people to think he signed Robinson because of politics.

Rickey never acknowledged the efforts of La Guardia or political progressives—not when he announced the signing of Robinson, nor when Robinson played his first game on April 15, 1947. Rickey wanted people to think that he—and only he—was responsible for the breaking of baseball’s color barrier, and in the ensuing years he would dictate this version of events to sportswriters and biographers.

To Daily Worker sportswriter Bill Mardo, Rickey was an opportunist who, nevertheless, fully supported desegregation and Robinson once he got behind the issue.

“There was the pre-Robinson Rickey who stayed shamefully silent for much of his baseball life,” Mardo wrote in 1998. And then there was the other Rickey “whose extraordinary business and baseball sense helped him seize the moment, jump aboard the Freedom Train as it was getting ready to pull out of Times Square, catch social protest at its apex, and then do just about everything right once he signed Robinson.”

Correction: A previous version of this story stated that Vito Marcantonio was a communist. He was a congressman.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.