Feminism, lately, is having an identity crisis. It’s an internal struggle that goes back decades, maybe even to the beginning of feminism. Its latest battlefield is Beyoncé, whose every move leaves a thousand thinkpieces in its wake. Not just Beyoncé, either, but other high-profile women such as Sheryl Sandberg, Lena Dunham, Emma Watson, and high-end women’s conferences and binge-watchable TV from Game of Thrones to Girls, too. At the heart of the crisis is the question of whether feminism means success for a few, who ascend the ladders of wealth and power, or whether it means fundamentally changing how wealth and power are redistributed, so that ladders are no longer needed.

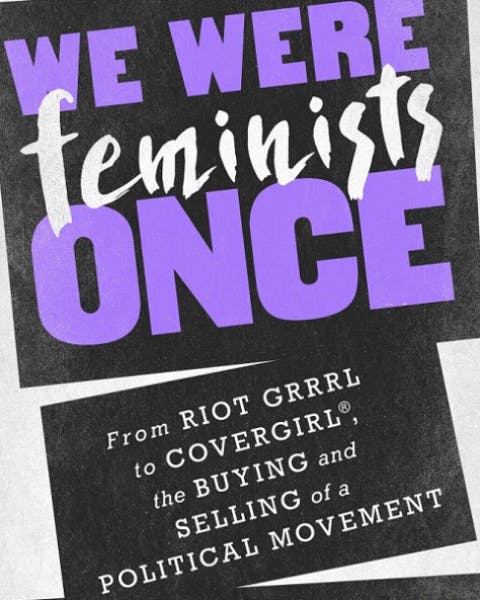

I picked a side in this fight a while back, and so I have been waiting rather excitedly for Andi Zeisler’s new book, We Were Feminists Once: From Riot Grrrl to CoverGirl, the Buying and Selling of a Political Movement. (This is where I disclose that Zeisler has edited me in the past for Bitch magazine, where she remains creative director.) In a political moment that has seen thrilling, radical new movements spring up around racial justice and economic inequality, the fact that mainstream feminism still seems so enthralled with neoliberalism has been a source of deep frustration to many. And yet when we attempt to argue about issues, we get bogged down in battles over personality; pointing out that the liberation of a CEO does little for her nanny is likened to “trashing.” The personality trap is itself a function of the problem that Zeisler has put a name to in her book: marketplace feminism.

In the world of marketplace feminism, she writes, “the fight for gender equality has transmogrified from a collective goal to a consumer brand.” It is a world where “purchasing itself [is] a feminist act,” where status is confused with liberation, where freedom is measured in what we consume or who we control, where what we wear, watch, and wax is more important than what we organize and fight for. Under marketplace feminism, feminism is a commodity to be purchased, an identity to proclaim and print on a T-shirt, a litmus test to be applied to other commodities, rather than a collective social movement that aims to change the structures of a sexist society. The problem with marketplace feminism is simple: marketplace feminism is good for capitalism, but what is good for capitalism is not necessarily good for women.

Zeisler avoids entering the war of personalities. Indeed, up front, she includes herself in her critique, noting that we are inundated with feminist critiques of pop culture, many of which owe their lineage to her work at Bitch, which has been publishing “a feminist response to pop culture” since 1996, with articles ranging from “Amazon Women on the Moon: Images of Femininity in the Video Age” (by Zeisler, from the magazine’s very early days) to updates on the battle of pop star Kesha to extricate herself from her record contract, which ties her to the man she says abused her. Meanwhile, abortion restriction bills and “bathroom bills” aimed at institutionalizing discrimination against transgender people proliferate, the gender wage gap continues, and women are the fastest-growing part of the prison population. These are problems, she notes, that will not be solved by marketplace feminism. They will require collective political action.

In writing this book, Zeisler aims to turn our attention back to systems, not individuals. The current moment in pop culture is obsessed with the latter: with the questions of which celebrity called herself a feminist this week, whether makeup can be feminist, if Game of Thrones is too “problematic” to be watched by right-thinking feminists. All of this has shrunk feminism down to the size of a pair of trendy panties; it has made it into yet another box to check off, another set of restrictions on what women can do.

It’s a particular kind of feminism that dovetails perfectly with the rise of neoliberalism—the period of capitalism that features deregulation, privatization, and hyper-individualism. Under neoliberalism, we are all entrepreneurs with “personal brands”; we are all free to choose whatever we want, as long as we can afford to. Neoliberalism has brought us the global supply chain, where fast fashion is sewn by women in sweatshops in Cambodia and Bangladesh, out of sight and mind from the women who will ultimately wear the clothing. Despite the cheery rhetoric of freedom and choices, its icon remains “Iron Lady” Margaret Thatcher, with her forbidding warning that “there is no alternative.”

The problem with “choice” as the key metric for feminism is that not everyone is actually free to make those choices, as Thatcher’s maxim ought to remind us. The point for feminism as a movement, then, is not to get into endless battles about whose choice is the feminist-est of them all, but to critique the ground we’re walking on, to change the rules of the game, not to hate the player.

Zeisler cites Marjorie Ferguson’s 1990 argument about the “feminist fallacy”—the idea that images of powerful women in the media translate into power for women out in the world. In this moment we too often fall under the spell of this and of another kind of “feminist fallacy”: that the success of powerful women will trickle down to the rest of us. In fact, as Zeisler notes, famous and powerful women often mistake what is best for them for what is good for all women; when we put too much weight on the feelings of celebrities, we end up cringing when their uninformed opinions, divorced from solidarity with anyone who might be affected, end up making headlines and even policy, as when Meryl Streep and Lena Dunham put their own feelings ahead of actual research and organizing on the subject of the decriminalization of sex work.

The ground zero for such celebrity obsession is the vortex around Beyoncé. Anytime the singer drops a track, a video, makes an appearance, or is spotted by the tabloids, the internet erupts with opinions on the feminism (or lack thereof) contained in whatever action she took. And yet, Zeisler writes, “The fascination with Beyonce’s feminism, the urge to either claim her in sisterhood or discount her eligibility for it speaks to the way that a focus on individuals and their choices quickly obscures the larger role that systems of sexism, racism, and capitalism play in defining and constraining those choices.”

In addition to the feminist fallacy, Zeisler introduces us to what she calls “feminism’s uncanny valley,” the space in which ideas, objects, and narratives offer a superficial similarity to feminism but upon a closer look, turn out to be “deeply unsettling.” Instead of liberation, they wind up being about “personal identity and consumption.”

Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In is of course the peak example of such an uncanny valley, but even more insidious than a self-help book for the upwardly mobile are corporate initiatives that purport to “empower” women. Take Walmart’s Women’s Economic Empowerment Initiative, launched just months after the Supreme Court ruled against the women in what would have been the largest-ever class action sex discrimination lawsuit, Dukes v. Walmart. The company undertook a massive PR operation to appear woman-friendly, when the most important thing Walmart could do to empower women economically would be to raise its bare-minimum wages. It took further collective action from Walmart’s workers to push the company, finally, into a small wage hike after a series of strikes and protests rippled across the country, led by workers like Venanzi Luna, Tyfani Faulkner, and Janet Sparks.

There are endless “initiatives” and “institutes” to “empower” women, almost all of which wind up being, as Wages for Housework movement organizer Selma James wrote in 1983, “jobs for the girls,” middle-class careers for a few women telling other women what they need in order to be empowered. It is, James wrote, “the process by which women’s struggle is hidden from history and transformed into an industry.”

I mention James here in order to underscore, as Zeisler does, that this struggle within feminism is not new. In 1984, in her book Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center, bell hooks criticized the development of feminism as identity to be claimed rather than action to be taken. “To emphasize that engagement with feminist struggle is political commitment, we could avoid using the phrase ‘I am a feminist’ (a linguistic structure designed to refer to some personal aspect of identity and self-definition) and could state, ‘I advocate feminism.’” There had been, she argued, “undue emphasis placed on feminism as an identity or lifestyle.”

And yet it is 2016, and here we are again. Selma James and bell hooks were always less media-friendly than some of their sisters, who came from different political traditions; Zeisler cites Rachel Fudge, from a 2003 Bitch article, to make the point that the feminist leaders anointed by the media, like Gloria Steinem, have always been those who seemed more marketable, regardless of whether they had been chosen as leaders within the movement itself. The feminism of the 1970s had a fraught relationship with the idea of leadership itself, struggling to come up with new structures for movement work that would be less hierarchical and less likely to privilege those who came from already-privileged backgrounds.

But marketplace feminism has simply embraced a mediagenic vision of leadership, most notoriously in the new women’s conference industry, where, Zeisler writes, attendees can “access and sell a certain kind of female power at a comfortable distance from the less individualistic and far less glamorous reality of the majority of women.” These conferences come with a hefty price tag to hear inspiring celebrities and CEOs’ tales about bootstrapping their way to the top and kicking sexism in the rear in stiletto heels. It’s a vision that, she notes, “erases the presence of anyone who isn’t empowered in the most crucial sense of the word—financially…” Feminism, Inc. is big business.

To become big business, though, feminism had to sand off all its rough edges. All movements, to be sure, are pressed to do so—just look at the chorus of pundits wringing their hands about the potential offensiveness of protests against Donald Trump or in favor of some measure of justice for black victims of state violence. Pander to those who might join the struggle and don’t dare say anything that might upset them, lest you lose their potential—always potential—support. “There are few activists who haven’t heard some variation on this theme,” Zeisler notes, “and though history confirms that social justice just doesn’t work that way, feminism in particular has been prone to internalizing the criticism.” Women, after all, are socialized to be nice, to make ourselves appealing. But if feminism is to be a movement that succeeds in changing the distribution of power in society, she points out, it’s going to make those who currently hold that power pretty uncomfortable.

To those well-versed in the history of feminism, much in this book will be familiar, but many of the connections she draws shed new light on that history: from suffragettes taking jobs in advertising to today’s “empowertising,” from riot grrrl to girl power to underwear printed with the word “feminism”. Others seem a bit more of a stretch—like the line Zeisler draws from 1970s radical feminist separatism to the high-powered women’s conference movement. But in each case, she aims to illuminate the route by which feminism arrived at its current state, to draw us all into the fight to make it better by showing us how we might have contributed to making it worse.

Zeisler’s years at Bitch show themselves in her accessible tone, even when she’s explaining tenets of Marxist theory; with few exceptions, the book is free of jargon. She offers occasional actual laugh-out-loud lines and self-deprecation alongside the quotations from scholars like Susan Bordo and Caryl Rivers, and opens a door for those who have found something wanting in marketplace feminism but were unsure how to express it, for those new to media criticism or criticism of neoliberal capitalism.

In a way, her book is most useful as a work of media criticism, when it turns the lens onto feminist media itself, and particularly onto the burgeoning “thinkpiece” industry, which she calls “one of marketplace feminism’s biggest triumphs: women who act on the illusion of free choice offered by the market and then offer it up to corporate media to capitalize on.” The endless personal essays wondering if this or that or the other act is feminist, excoriating it for being unfeminist, or confessing to liking said unfeminist thing wind up circling back around to the writer’s personal choices and feelings. Those writers, it should be noted, are paid a pittance to feed the content mill: the personal essay industry itself could be the site of collective struggle for labor rights.

That is the crux of the problem: those who advocate feminism need to move beyond what at its worst appears to be, in Zeisler’s words, “a deeply heteronormative, white- and middle-class-centric movement that’s become hopelessly stuck up its own ass.” There are signs aplenty that this is already happening; there is a rising turn toward a feminism that sees capitalism as the problem, rather than the solution, particularly among young people who have been served badly by the rising cost of education, the supposed “recovery” from the financial crisis, the drug war, and the looming specter of climate change. In recent months I have been heartened to discover writers like Holly Wood, who dismiss simple cheerleading for Team Woman and openly claim the title of socialist. The movement for black lives is guided by brilliant black feminists like Charlene Carruthers, Alicia Garza, Janae Bonsu, Ciara Taylor, and many more that I don’t have space to name.

If marketplace feminism is a way to promise the powerful that feminism poses no real threat to the status quo, this anti-market feminism isn’t afraid to frighten the powerful. It is based in collective struggle. It is the only thing that will make change. Pop culture is a wonderful thing—I listened to Beyoncé while writing this review—but it is possible to spend too much time on it. We should remember that the best art evokes the world that exists, from Loretta Lynn singing about the Pill to Bey sinking that police car. If we change the world, pop culture will come along. There’s no guarantee that the reverse is true.