No group is more intensely anti-Trump than black Americans. According to an April poll conducted by ABC News and The Washington Post, an astonishing 91 percent of black Americans have an unfavorable view of the presumptive GOP nominee—more than Latinos (81 percent) or women (75 percent). Trump’s overwhelming unpopularity with blacks might seem strange, given the fact that as a presidential candidate he hasn’t directly targeted them the way he has Mexican and Muslim immigrants. But in the past Trump has done more than enough to earn the abiding enmity of black Americans, beyond his outspoken birtherism challenging the legitimacy of the first black president: He has a long history of alleged racist policies as a landlord, and in 1989 he called for the execution of five black teenage boys in the infamous “Central Park Five” rape case (the teens had not been tried at that point, and were later found innocent).

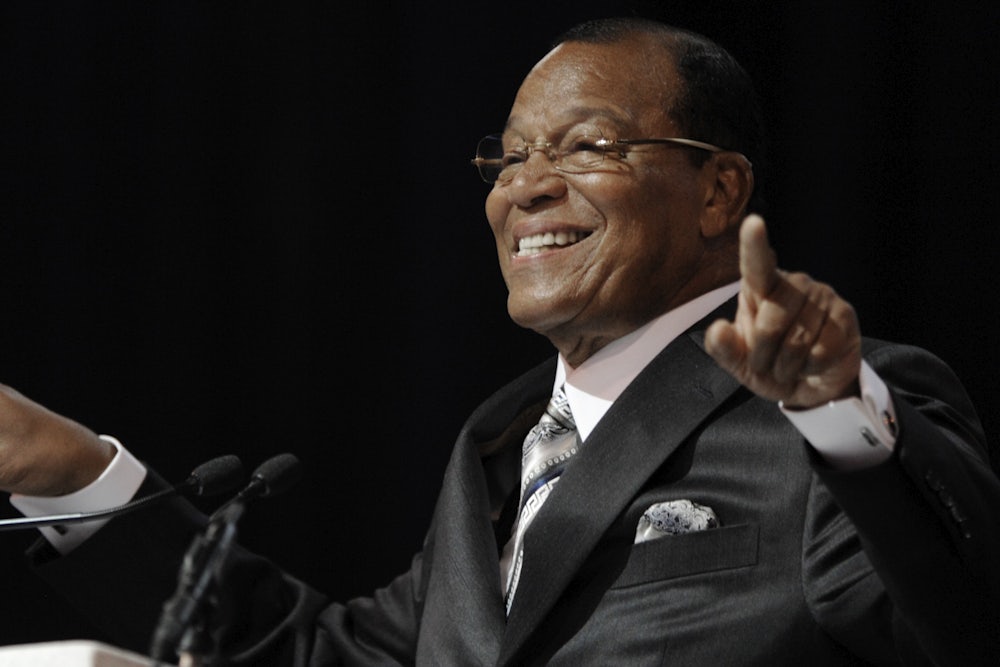

Yet if nearly all of black America dislikes Trump, he does have a few supporters, notably former rival Ben Carson, basketball player Dennis Rodman, and the boxer Mike Tyson. One of the most curious of Trump’s fans is Nation of Islam (NOI) leader Louis Farrakhan. While Farrakhan hasn’t explicitly endorsed Trump, he speaks of him in effusive terms, while being sharply critical of Trump’s likely general-election rival, Hillary Clinton, who he’s compared to Satan and called a “wicked woman” responsible for the destruction of Libya.

Speaking to conspiracy-monger Alex Jones earlier this year, Farrakhan celebrated many of Trump’s policies—including, strangely enough, his call to keep Muslims out of the United States. (Farrakhan’s argument was that American foreign policy had created many enemies among Muslims, so they have to be carefully vetted before being allowed to enter the United States.) Farrakhan also told Jones he “admired” Trump’s self-financed campaign. “When a politician does not want money from the rich, he’s freer than the others to really do good for the masses of the people,” he said. “I think today we are in the midst of the darkest hour in American history and so if we don’t make the right move with the right people at the right time, the America that we know, we’re not going to see it become great again. ... He’s free, he’s rich, he hates political correctness and rightly so.”

So far, Farrakhan hasn’t responded to Trump’s flip-flop decision to start accepting donations from wealthy donors. In a sermon praising Trump, Farrakhan took particular delight in remarks Trump made to Jewish donors in December: “You’re not going to support me because I don’t want your money. ... You want to control your own politicians.” The religious leader interpreted these words as anti-Semitic dog whistles.

Farrakhan is no longer the political powerhouse he was back in the 1990s when he led the Million Man March in Washington, D.C., bringing hundreds of thousands of black men to the city to promote a message of responsibility and self-improvement. But he’s still the most famous spokesperson for the venerable and controversial tradition of black nationalism. And within that tradition, there’s a long historical precedent for Farrakhan’s view of Trump.

Going back more than a century, there has been a strain of black nationalist thought that argues overtly racist whites make better allies than white liberals or integrationists. The reasoning is partly that white racists are more honest, but also that there is a political overlap between white racists and black nationalists in trying to maintain the separation of the races.

In 1922, Marcus Garvey, a seminal figure in black nationalism and founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League, met in Atlanta with Edward Young Clarke, the imperial wizard of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. The purpose of this summit was to try and find common ground on issues like preventing miscegenation. But Garvey’s meeting with the Klan provided ample ammunition for his critics in other black organizations, notably the NAACP, which used the meeting to discredit Garvey.

Garvey’s meeting with Clarke had a sequel decades later. In 1961, Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Nation of Islam, sent one of his main followers, Malcolm X, to Atlanta to secretly meet with the KKK and arrange a truce, with the NOI supporting racial segregation in exchange for the Klan promising not to harm mosques.

Later that same year, the Nation of Islam invited George Lincoln Rockwell, head of the tiny American Nazi Party, to address a Black Muslim rally in Washington, D.C., where Malcolm X was the main speaker. The crowd of 8,000 was far larger than anything Rockwell was used to. When he spoke at another Nation of Islam rally in Chicago in 1962, Rockwell tried to explain the overlap between his white supremacy and black nationalism.

“I am not afraid to stand here and tell you I hate race-mixing and will fight it to the death,” Rockwell said. “But at the same time, I will do everything in my power to help the Honorable Elijah Muhammad carry out his inspired plan for land of your own in Africa. Elijah Muhammad is right. Separation or death!” While Elijah Muhammed might have liked what Rockwell was saying, the crowd of more than 12,000 was hostile, and often booed. Muhammed didn’t succeed in convincing his own followers to like Rockwell, just as Farrakhan will surely fail to win many black followers for Trump.

When Malcolm X broke with the Nation of Islam, he cited the alliance with the Klan as one of the reasons he could no longer accept the leadership of Elijah Muhammed. A week before his assassination, Malcolm X told the press, “I know for a fact that that there is a conspiracy between...the Muslims and the Lincoln Rockwell Nazis and also the Ku Klux Klan.” What Malcolm X came to realize was that the idea of blacks finding any security in alliances with white racists was an illusion. That illusion has a long history, and Farrakhan shows it is still alive. But the heroic, truth-telling Trump who Farrakhan imagines is a creation of his imagination, a wraith, no more real than the hopes that Farrakhan’s predecessors put in Klansmen and Nazis. Fortunately, the vast majority of black Americans know that.