A fascinating 1964 New Yorker story from the Barry Goldwater campaign trail gives you the uneasy feeling that we’re trapped in an endless loop. It describes rallies that sound just like Donald Trump’s—absurd, crazy, weird, and big enough to fill a stadium. But there’s one telling difference that suggests we’ve been overthinking the 2016 campaign: Barry Goldwater was a terrible showman.

Goldwater, in reporter Richard H. Rovere’s telling, is uncharismatic. He is not consistent and he doesn’t stay on message. He’s not a thrilling insult comic. He doesn’t sell Goldwater steaks or suggest that you, too, could be lifted from your working-class existence to become a billionaire. All that matters is the racism—the sense that he would stop integration.

That’s why Goldwater’s rallies were so ecstatic. Likewise, in Trump’s campaign the party is the draw. But Trump is a fool to think the party is for him.

“By coming South, Barry Goldwater had made it possible for great numbers of unapologetic white supremacists to hold great carnivals of white supremacy,” Rovere writes. “They were not troubled in the least over whether this would hurt the Republican Party in the rest of the country.” Sounds familiar, right?

Much has been written—including by me!—analyzing Trump’s ability to put on a spectacle. On Tuesday, The New York Times posted a big feature analyzing Trump’s fabulous news conferences. The Trump rally, meanwhile, has taken on mythic proportions. But nothing Trump has done so far can compare to this Goldwater rally in Montgomery, Alabama. (The whole story is worth reading, but excessive ellipses are necessary because The New Yorker was even wordier back then):

Some unsung Alabama Republican impresario had hit upon an idea of breathtaking simplicity: to show the country the “lily-white” character of Republicanism in Dixie by planting the bowl with a great field of white lilies—living lilies, in perfect bloom and gorgeously arrayed. ...

And springing from the turf were seven hundred Alabama girls in long white gowns, all of a whiteness as impossible as the greenness of the green. ... The girls stood on the turf, each waving a small American flag. ... Then, right on schedule, an especially powerful light was focussed on a stadium gate at about the fifty-yard line, and the candidate of the Republican Party rode in as slowly as a car can be made to go, first past fifty yards or so of choice Southern womanhood and then, after a sharp left at the goal line, past more girls and up to the splendidly draped stand.

It was all as solemn and as stylized as a review of troops by some master of the art like General de Gaulle. The girls did not behave like troops. ... Yet in a sense, of course, they were Goldwater’s troops, as well as representatives of what the rest of his Southern legions—the thousands in the packed stands, the tens of thousands in Memphis and New Orleans and Atlanta and Shreveport and Greenville—passionately believed they were defending. When at last he mounted the platform, the lilies departed the gridiron and arranged themselves on the sidelines. There they listened to what was by far the limpest speech Goldwater delivered anywhere in the South. It wasn’t about anything in particular. ...

The crowd loved it. It may even have been relieved that the speech was low in key and did not drive out memories of the spectacle that had preceded it.

Goldwater was a droner. “The lines he got from his writers were as flat as his delivery of them,” Rovere writes. Even when being inflammatory, he spoke in dull statistics. But that didn’t dull the enthusiasm of his crowds. “The aim of the revellers was not so much to advance a candidacy or a cause as to dramatize a mood, and the mood was a kind of joyful defiance, or defiant joy.” They were defying elite opinion that segregation had to come to an end.

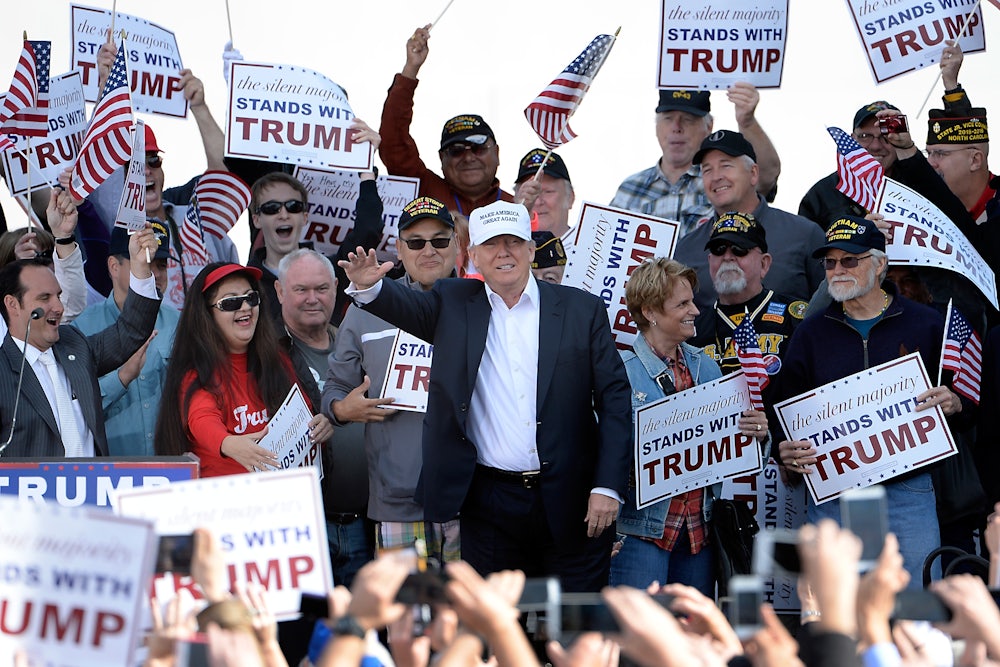

The tone at Trump’s rallies is also defiant. A Politico story in March: “Trump events are electrified by the feeling that these people, too—many white, working- and middle-class—can be marginalized, and they’re tired of the muzzling effect of political correctness that keeps them from saying so.” They are full of energy and the threat of violence. Protesters are part of the show—people of color emerge from the crowd to dispute Trump’s claims, and he or the police shut them down to great cheers.

For decades, the GOP has bashed anyone from New York who seeks out celebrity, who cares about aesthetics, who talks with their hands, as an effete elite. And now its voters are embracing a guy who does all of those things. Is this because of Trump’s genius and media savvy? The tone in political coverage would have you believe this is the case.

“With shrewd showmanship and calculated irreverence, his year-old candidacy has turned the tired ritual of holding court from behind a lectern into a frequently riveting spectacle of self-promotion and media manipulation,” Times reporters Michael Barbaro and Jessica Dimson write. Trump’s presidential announcement speech in June got “uniformly awful” reviews, they say. “But it was no accident. That much-mocked news conference planted each of the thematic seeds (immigration, rage, anti-elitism) that have propelled him toward the Republican nomination.” The parenthetical suggests these are three different things. But they are one thing: rage that elites demand acceptance of immigration.

Obama campaign strategist David Axelrod likes to say, “You’re never as smart as you look when you win, and never as dumb as you look when you lose!” Has this ever been more true than in the case of Donald Trump? On the stump, Trump is not that great. He rambles. He’s an absolute failure at faking religious feeling. He can’t get basic local details right—in March, The Atlantic noted that at a North Carolina rally, Trump praised Tom Brady, seemingly unaware he was in Cam Newton land. (Remember when John Kerry was basically a war criminal because he ordered the wrong cheese on a locally beloved sandwich?) As with Goldwater, this would be a disaster, if he didn’t have one thing going for him.

In 1964, The New Yorker argued, “The Goldwater movement, whether or not it can command a majority, remains an enormous one in the South and appears to be a racist movement and almost nothing else. On his tour, Goldwater seemed fully aware of this and not visibly distressed by it.” Most of the time, journalists want to believe that substance matters more than style. In the case of Trump, many of us want to believe that it cannot be his awful substance that’s the core of Trump’s appeal. But it is! Trump’s rallies are big parties not because of his charisma but because he says he wants to kick Mexicans out of the country and keep Muslims from coming in. That’s it. There’s no more there. This doesn’t take savvy. It takes shamelessness.