Miami

Just before the bell for the seventh round, Cassius Clay got up to go about his job. Suddenly, he thrust his arms straight up in the air in the signal with which boxers are accustomed to treat victory and you laughed at his arrogance. No man could have seen Clay that morning at the weigh-in and believed that he could stay on his feet three minutes that night. He had come in pounding the cane Malcolm X had given him for spiritual support, chanting “I am the greatest, I am the champ, he is a chump.” Ray Robinson, that picture of grace who is Clay’s ideal as a fighter, pushed him against the wall and tried to calm him, and this hysterical child turned and shouted at him, “I am a great performer, I am a great performer.”

Suddenly almost everyone in the room hated Cassius Clay. Sonny Liston just looked at him. Liston used to be a hoodlum; now he was our cop; he was the big Negro we pay to keep sassy Negroes in line and he was just waiting until his boss told him it was time to throw this kid out.

British journalists who were present remembered with comfort how helpful beaters like Liston had been to Sanders of the River; Northern Italian journalists were comforted to see on Liston’s face the look that mafiosi use to control peasants in Sicily; promoters and fight managers saw in Clay one of their animals utterly out of control and were glad to know that soon he would be not just back in line but out of the business. There were two Catholic priests in attendance whose vocation it is to teach Sonny Liston the values of organized Christianity, and one said to the other: “Do you see Sonny’s face? You know what he’s going to do to this fellow.”

The great legends of boxing are of managers like Jack Hurley, who had taken incompetent fighters and just by shouting their merits, against all reason built them up for one big payday at which they disgraced themselves and were never heard from again. Clay had created himself the way Hurley created his paper tigers. His most conspicuous public appearance in the week before he was to fight had been a press conference with the Beatles. They were all very much alike—sweet and gay. He was an amateur Olympic champion who had fought twenty professional fights, some of them unimpressive; and he had clowned and blustered about how great he was until he earned his chance from a Liston who, if he could not respect him as an opponent, could recognize him as a propagandist skilled enough to fool the public. A reporter had asked Liston if he thought the seven to one odds against Clay were too long, and he answered: “I don’t know. I’m not a bookmaker. I’m a fighter.” But there was no hope Clay could win; there was barely the hope that he could go like a gentleman. Even Norman Mailer settled in this case for organized society. Suppose Clay won the heavyweight championship, he asked; it would ‘mean that every loudmouth on a street corner could swagger and be believed. But if he lay down the first time Liston hit him, he would be a joke and a shame all his life. He carried, by every evidence unfit, the dignity of every adolescent with him. To an adult a million dollars may be worth the endurance of being clubbed by Sonny Liston; but nothing could pay an adolescent for just being picked up by the bouncer and thrown out.

On the night, Clay was late getting to the dressing room and he came to stand in back of the arena to watch his younger brother fight one of the preliminaries, He spoke no word and seemed to look, if those blank eyes could be said to look, not at the fighters but at the lights above them. There was a sudden horrid notion that just before the main event, when the distinguished visitors were announced, Cassius Clay in his dinner jacket might bounce into the ring, shout one more time that he was the greatest, and go down the steps and out of the arena and out of the sight of man forever. Bystanders yelled insults at him; his handlers pushed him toward his dressing room, stiff, his steps hesitant. One had thought him hysterical in the morning; now one thought him catatonic.

He came into the ring long before Liston and danced with the mechanical melancholy of a marathon dancer; it was hard to believe that he had slept in forty-eight hours. Liston came in; they met in the ring center with Clay looking over the head of that brooding presence; then Clay went back and put in his mouthpiece clumsily like an amateur and shadowboxed like a man before a mirror and turned around, still catatonic and the bell rang and Cassius Clay went forward to meet the toughest man alive.

He fought the first round as though without plan, running and slipping and sneaking punches, like someone killing time in a poolroom. But it was his rhythm and not Liston’s; second by slow second, he was taking away the big bouncer’s dignity. Once Liston had him close to the ropes—where fighters kill boxers—and Clay, very slowly, slipped sideways from a left hook and under the right and away, just grazing the ropes all in one motion, and cut Liston in the eye. For the first time there was the suspicion that he might know something about the trade.

Clay was a little ahead when they stopped it. Liston had seemed about to fall on him once; Clay was caught in a comer early in the fifth and worked over with the kind of sullen viciousness one cannot imagine a fighter sustaining more than four or five times in one night. He seemed to be hurt and walked back, being stalked, and offering only a left hand listlessly and unimpressively extended in Liston’s face. We thought that he was done and asking for mercy, and then that he was tapping Liston to ask him to quiet down a moment and give the greatest a chance to speak, and then we saw that Clay’s legs were as close together as they had been before the round started and that he was unhurt and Liston just wasn’t coming to him. It ended there, of course, although we did not know it.

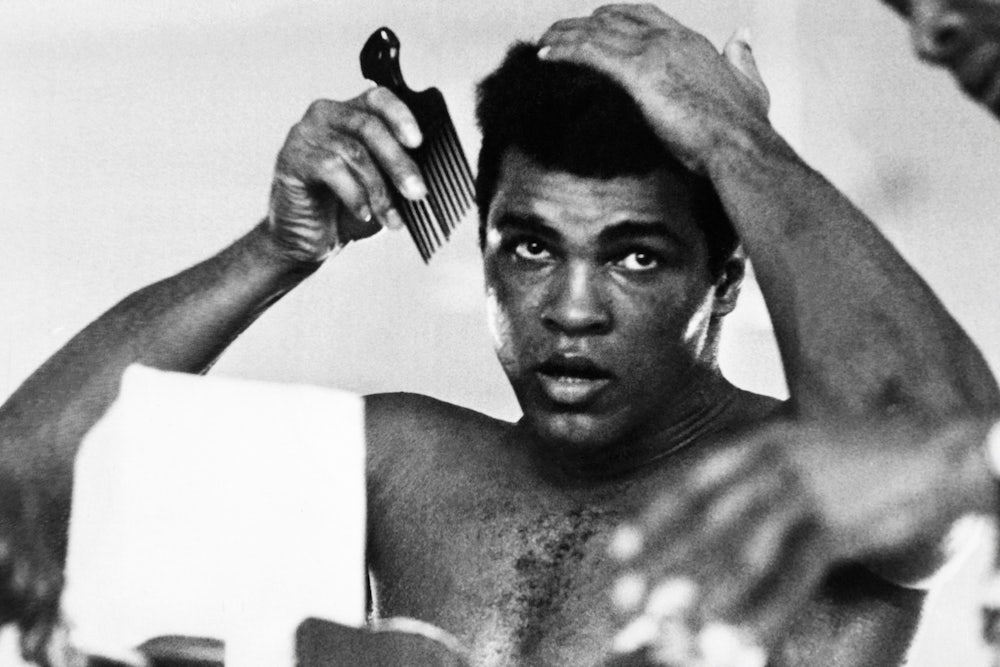

“I told ye’,” Cassius Clay cried to all of us who had laughed at him. “I told ye’. I just played with him. I whipped him so bad and wasn’t that good. And look at me: I’m still pretty.”

An hour later, he came out dressed; a friend stopped him and the heavyweight champion of the world smiled and said he would be available in the morning. His eyes were wise and canny, like Ray Robinson’s.