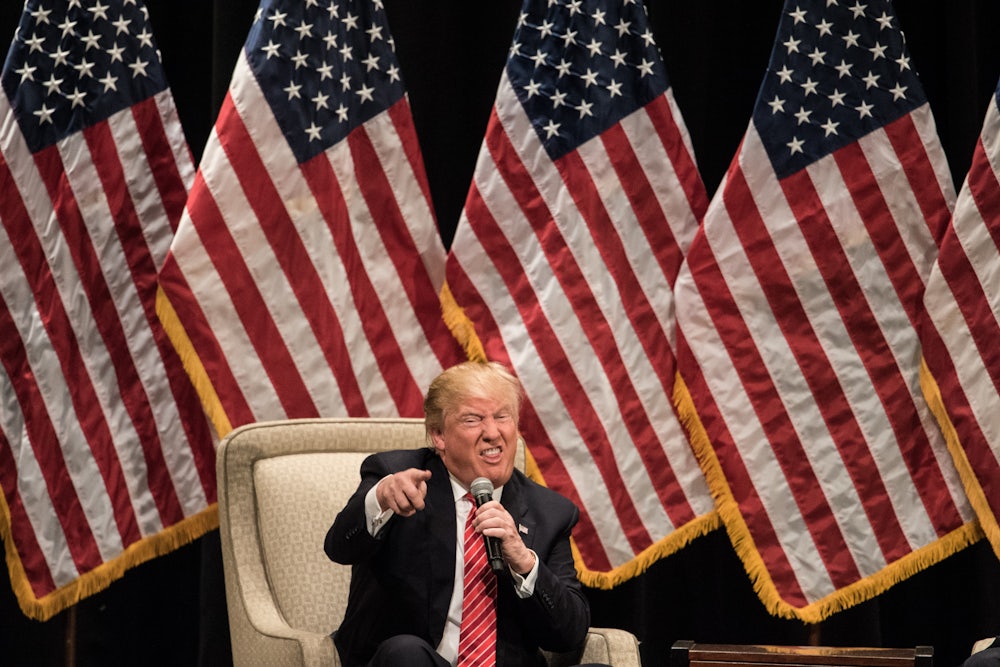

Is Donald Trump a white trash icon? His hair is as teased and artificial as Dolly Parton’s; his eternally pursed lips recall Elvis’s, minus the sensuality; his orange skin suggests the kind of cosmetic mask that Tammy Faye Bakker once kept between herself and her viewers. Ten years ago, he even went so far as to gamely don a pair of overalls and perform the Green Acres theme, alongside a giggling Megan Mullally, at the Emmys.

Today, commentators who try to make sense of Trump’s mass appeal often fall back on “white trash” signifiers, even if the term itself never rises above the level of subtext. A recent New York Times article announced that counties most likely to contain Trump supporters were also likely to be populated by mobile home residents who had no high school diplomas, worked “old economy” jobs, and listed their ancestry as “American” on the U.S. census. Trump’s public persona is the kind of brash, ball-busting bully you want on your side when you have become convinced that no one else will stand up for you. His campaign strategy may be unfamiliar to the democratic process—or at least to its public face—but he comes from a long and well-established tradition of heavies, henchmen, and block bosses. He is, in other words, the kind of leader who might well be called on by a population demographer William Frey described to the Times as “nonurban, blue-collar and now apparently quite angry.” Or, to put it in the kind of blunt terms we associate with the candidate: White trash.

If Trump’s success has indeed been driven by the “nonurban, blue-collar” and “quite angry,” then he is only exploiting a demographic that is as integral to American identity as the Founding Fathers. “The white poor,” historian Nancy Isenberg writes in her new book White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America,

have always been with us in various guises, as the names they have been given across centuries attest: Waste people. Offscourings. Lubbers. Bogtrotters. Rascals. Rubbish. Squatters. Crackers. Clay-eaters. Tackies. Mudsills. Scalawags. Briar Hoppers. Hillbillies. Low-downers… They are renamed often, but they do not disappear. Our very identity as a nation, no matter what we tell ourselves, is intimately tied up with the dispossessed.

White Trash is a dizzying, dazzling four-hundred-year-long tour of American history from Pocahontas to Sarah Palin, seen from a vantage point that students of American history occupy all too rarely: that of the disposable citizens whose very presence disrupts what Isenberg calls our “national hagiography.”

The book’s first section is in many ways its most compelling. In it, Isenberg demonstrates that colonial America could never have existed without a large and forgotten class of “waste people”: the convicts and orphans and indentured servants who made America habitable for religious extremists and political idealists.

Isenberg’s argument is based on painstakingly supported factual analysis, and studded with narratives as horrific—and as disturbingly familiar—as that of Jamestown’s Jane Dickenson, the wife of an indentured servant. Captured by Native Americans in 1622, she was freed nearly a year later only to find that she owed an exorbitant sum to her dead husband’s master. Jane’s husband had not lived long enough to complete his period of indenture, so it was Jane’s job to work it off for him. The specter of indentured servitude itself—in which servants worked off the cost of their passage to the colonies on arrival—is chillingly familiar in an America where debt can follow us across national borders, through the decades, and even beyond the grave.

Yet perhaps even more illuminating is Isenberg’s conception of the role America played in the British imagination. From the beginning, Isenberg shows us, America was, to many Britons, not a “Citty upon a Hill” or a “Holy Experiment,” but a cesspool. “During the 1600s,” Isenberg writes, “Far from being ranked as valued British subjects, the great majority of early colonists were classified as surplus population and expendable ‘rubbish.’” When it came to disposing of the “rubbish” class, the theory went that:

Either nature would reduce the burden of the poor through food shortages, starvation, and disease, or, drawn into crime, they might end up on the gallows. Finally, some would be impressed by force or lured by bounties to fight and die in foreign wars, or else be shipped off to the colonies… Once there, it was hoped, the drones would be energized as worker bees.

Before we had a government or even a national identity, we had a foundation of disposable Americans who could best play their mandated role in society by either working or dying. But what do we do with those perverse individuals who refuse to do either? What do we do with those Americans who can neither be “energized as worker bees,” nor relied upon to relieve their country of the burden of providing for them?

“Those who fail to rise in America are a crucial part of who

we are as a civilization,” Isenberg writes. Perhaps most meaningfully, they

demonstrate that America is and always has been a country where one can fail to rise: A country where debt

begets debt and money dries to nothing, where poverty is inescapable, and where

there is and always has been liberty and justice for some.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Donald Trump’s campaign has been his ability to turn disenfranchised citizens into “worker bees” by alchemizing their alienation into votes. Such a class of Americans has always existed, and so has their often all too justified belief that their government is unable or unwilling to provide for their needs. Whether Trump’s success suggests an increase in this demographic’s size is ultimately less relevant than the question of why, as Americans, we remain so compelled to perpetuate a mythology that ignores our country’s very foundation—and what might happen, quite simply, if we accepted our heritage as a trash nation. Would doing so allow us to better care for the Americans we have done our best to forget?

White Trash loses some of its vitality as Nancy Isenberg leaves behind the wreckage she has handily made of early American rhetoric, and draws toward the present day. Despite her nuanced examination of such white trash icons and chroniclers as James Agee, James Dickey, Jimmy Carter, and Elvis Presley, these chapters pale in comparison to the finely-wrought destruction Isenberg wreaks on America’s founding narratives. Of all the contemporary figures Isenberg explores, however, perhaps the most revealing are those who have been able to simultaneously embody America’s white trash dreams and nightmares. Nowhere is this quality more compellingly on display than in The Andy Griffith Show, and in the show’s bitter, forgotten cousin, Elia Kazan’s 1957 film A Face in the Crowd, which Isenberg also examines.

A Face in the Crowd stars Griffith as Lonesome Rhodes, a redneck drifter who becomes first a pop culture sensation and then a down-home kingmaker, all while remaining, Isenberg writes, “a volatile mix of anger, cunning, and megalomania.” For Lonesome Rhodes, the ride ends when a hot mic reveals him to his adoring public as a crude and hateful tyrant in the making. Today, it seems that no such accident could harm Donald Trump’s, whose speeches are based less on any rhetorical tradition than on the primal scream. As long as voters believe Trump is screaming for them, and not at them, they have no reason to leave his side.

Perhaps the only accident that could hurt Trump’s numbers

would be a hot mic that revealed him as thoughtful, empathetic, or even kind.

So far, the closest thing we have to a moment like this might be a scene from a

2007 episode of The Apprentice, in which Trump took sudden and surprising umbrage at a contestant

describing himself as “white trash.”

“You shouldn’t use that expression anymore,” Trump said, after firing the contestant. “It’s a terrible expression. It’s not a nice expression.”

If Donald Trump sees white trash as his core demographic, he isn’t telling. Doing so, after all, might mean facing the fact that his constituents are drawn to him not because they are impassioned by his message, but because they have been rendered voiceless for so long that they are happy to have anyone speak on their behalf. It might mean facing the fact that his own rise, in business and in politics, is based on exploiting others’ weakness. It might mean realizing that such a vast class of desperate, marginalized people has always existed but does not need to exist, and that, if America was “great,” there would simply be no one left to vote for him.