Some might think of Bruce Jenner and a box of Wheaties. For me, though, the track and field events at the Olympics have always been about a kind of racial politics. “What do you remember about the Olympics?”, I’m asked. And my first instinct, in answering, is to count off a set of names on the tips of my fingers: Jim Thorpe. Jesse Owens. Carl Lewis. Florence Griffith-Joyner. Gail Devers. My second instinct is to recognize the symbolism of these names in our memories of American success at the games, to see in their victories, in their hands raised in victory, and in their smiling press photos the outline of our beloved metaphors of multiculturalism, diversity, and pluralism.

The image of people of color with gold medals has a history of being used to support official optimism about the state of race-relations in the U.S. It is all too easy, in a country famous for its love of a bootstrapping biography, to turn a win for anyone dispossessed or marginalized into a balm for concerns about structures, institutions, and power.

The instinct to critique when asked about the Olympics runs, I suppose, counter to the official spirit of the games. We’re supposed to focus on the bright lines of nationality, and not the haunting fractures that weaken a nation’s claim to be unified. We’re supposed to focus on the medal count, the pageantry, the identifying markers on the uniform, and the chants of “U-S-A, U-S-A…” We aren’t supposed to see the social cleavages and broken promises of our day. Whatever we are going to see in Rio, it isn’t supposed to remind us of Baltimore. Indeed, it is meant, in some fashion, to make us forget what is on the ground right here and right in front of us.

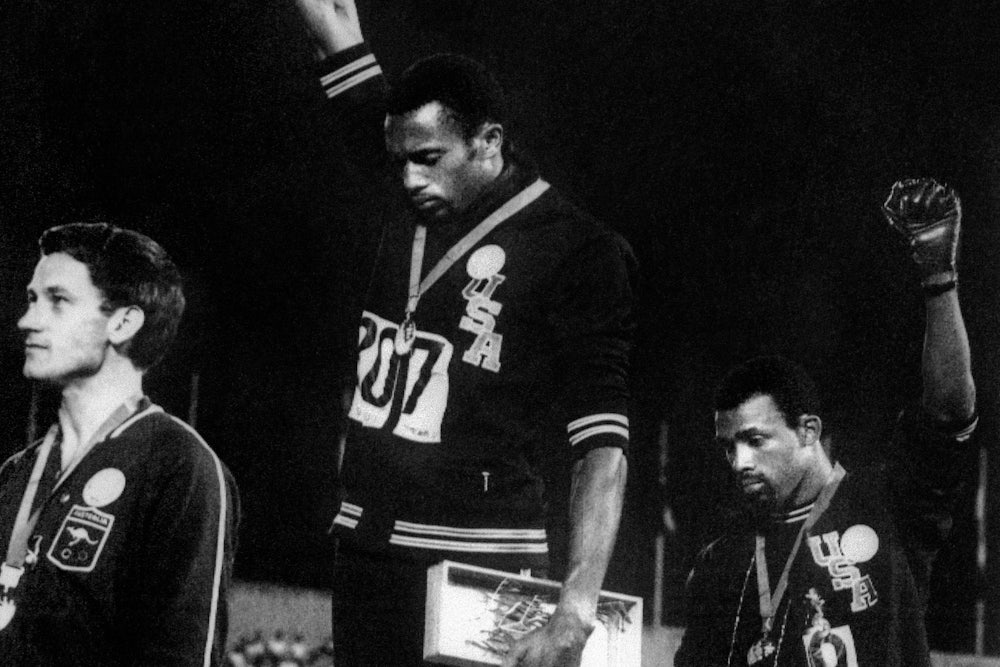

I think of race when I think of track and field not because so many athletes of color have done so incredibly well, but chiefly because of Tommie Smith and John Carlos, winners of the gold and bronze medals at the 1968 Olympics, who courageously stood with their fists raised in a black power salute as the Star-Spangled banner played during the awards ceremony. Theirs was an unprecedented gesture of polite defiance. And a reminder, too, of the painful reality of those fractures and broken promises, as revealed in the disconnect between those black gloves clenched tightly, those heads bowed low, and the displaced nationalism of those red, white, and blue track suits.

The Olympics wants to be seen one way. It has an argument to make and it wants us to listen. But no matter how triumphant the broadcast from Rio, no matter how dazzling the pageantry, no matter who wins, that simple, timeless protest from 1968 lingers in my memory. It makes me want to look for something else, some new reminder that, beyond the manicured green fields and pristine tracks, our nation is far, far from perfect.