Attorney-client privilege is more binding than marriage, and in some ways more intimate. If a husband describes his most profound ethical transgressions to his wife, she is free to seek protection from him, or at least free to share what he has told her with someone else. She can widen their world enough that she does not find herself alone with him and his confidences, and, if this is not enough, she can dissolve the partnership. Even in the absence of divorce, the bonds of marriage only last until death. The attorney-client relationship is a little bit stickier. In 1998, with Swidler & Berlin v. United States, the Supreme Court ruled that a lawyer could not be forced to disclose their client’s secrets even after that client’s death. Some mysteries, in other words, may never be solved.

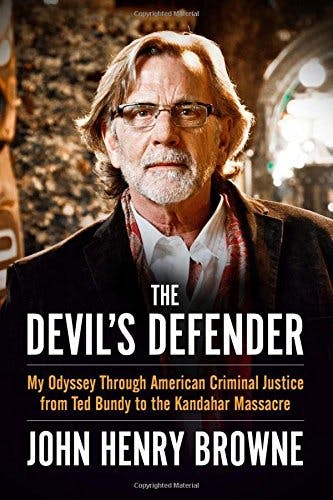

But some will. That, at least, is the marketing strategy for John Henry Browne’s memoir The Devil’s Defender: My Odyssey Through American Criminal Justice from Ted Bundy to the Kandahar Massacre. Browne’s book is not the first one to be published by one of Ted Bundy’s lawyers, and in fact isn’t even the first to invoke Satan: That distinction goes to Polly Nelson, author of Defending the Devil, and Bundy’s post-conviction lawyer in the years leading up to his execution. Still, Browne squeezes into second place, and for that he should be grateful.

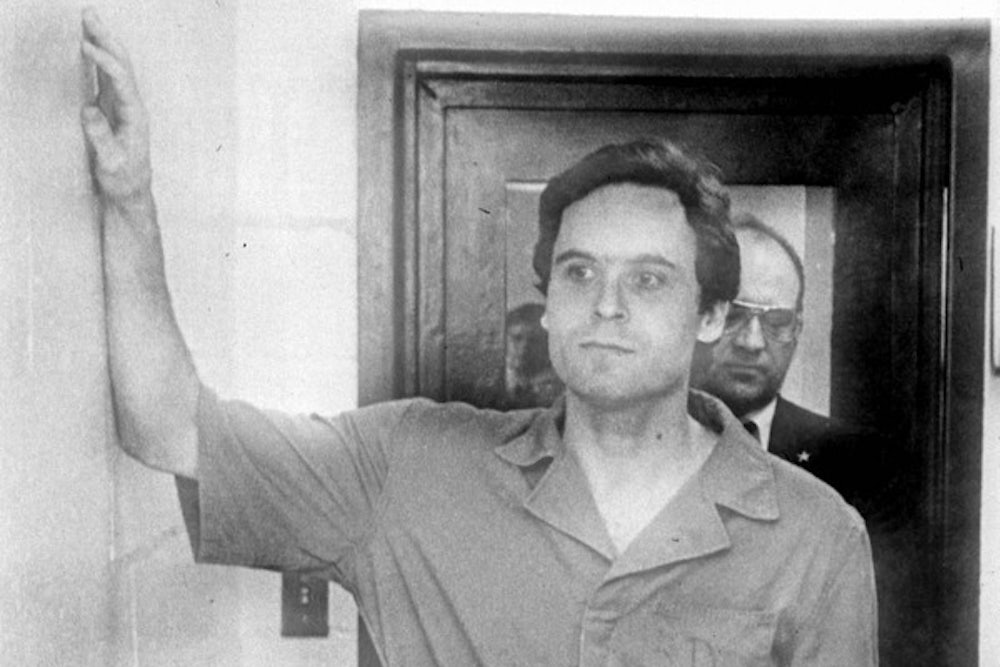

Between his first arrest in 1975 and his execution in 1989, Bundy went through lawyers about as quickly as most people go through packs of gum. He had different attorneys in Utah, Colorado, and finally in Florida, where he first decided to act as his own counsel, then accepted the help of a team of public defenders who resigned in frustrated exhaustion as his erratic behavior in the courtroom all but systematically sabotaged his own right to a fair trail.

If every lawyer who ever represented Ted Bundy wrote a book about their most famous client, we might know all we could ever want to about America’s most iconic serial killer. But we could also end up knowing next to nothing—at least if every one of these books were like John Henry Browne’s.

Browne first represented Bundy at the start of his legal troubles, after he was arrested in Salt Lake City and began preparing to face what he described to Browne as “this little stupid” attempted kidnapping charge. Browne was a Seattle criminal defense attorney almost exactly the same age as Bundy, and initially seemed to fascinate his client, who had just finished his first year of law school, more than his client fascinated him. “I could see Ted trying to get closer and closer to me,” Browne writes.

He started asking where I purchased my clothing and what books, movies, and television shows I enjoyed. If I told him I’d bought, say, my penny loafers at The Bon Marché, the next time I saw him, I swear to God, he’d be wearing the same penny loafers. I embarrassed him once when he arrived with actual pennies tucked into the shoe creases. I laughed and said, “Ted, that hasn’t been a thing since the early 1960s.”

Browne’s memoir—little of which directly deals with Bundy, since Browne spent little time representing him—makes it easy to see why Ted Bundy tried to emulate his young lawyer. Ted Bundy cultivated surface charm because he didn’t know how to talk to people, and radiated the illusion of success because he was never quite able to establish himself in a career. His need for a vocation seemed, in some ways, to reflect his lack of a real identity.

In interviews conducted while he was on death row, he would tell writers Stephen G. Michaud and Hugh Aynesworth that the first time he ever felt able to make friends or succeed at his job was when, at 21 years old, he worked for Seattle politician Dan Evans’s 1968 gubernatorial campaign. After the campaign ended, so did his sense of security, and perhaps even his sense of self. When, in Florida, Bundy went to trial for the murders of three victims—Lisa Levy, Margaret Bowman, and Kimberly Leach—and was publicly linked to the deaths of dozens more, he clung to the role of lawyer, arguing either ineffectively or disastrously on his own behalf. The more public opinion wrenched “Ted Bundy” out of the category of “human,” the more determined he was to paint himself as someone educated, intelligent, and respected: an attorney.

Even as a young man in the 1960s, John Henry Browne had the kind of life Ted Bundy appears to have longed for. He was untroubled by questions of who he was and how to find his place in the world, and was instead always searching for the next adventure, the next challenge, the next chance to either get in trouble or save the world. (And sometimes—the greatest dream of the decade—to do both things at once.) Browne fell into easy friendships and romantic intimacies, and toured with a rock band, until the siren song of social justice lured him to law school. He went undercover as an inmate to research prison conditions, and came within inches of dosing Spiro T. Agnew with LSD before the then-vice president made a TV appearance.

This is the kind of shaggy dog story The Devil’s Defender is filled with, and it’s one that will be familiar to anyone who has sat through a dinner party with a proud veteran of the sixties: Something almost happened, the story goes, and things almost changed forever, but then they didn’t and now here we are, and wasn’t it fun while it lasted?

It seems inevitable, at least from a marketing perspective, that John Henry Browne’s scant interactions with Ted Bundy would be sold as the centerpiece of his career. It is, unfortunately, even less surprising that Browne’s book boasts previously untold revelations about Bundy’s crimes: Browne can’t be compelled to spill his former client’s secrets, but he can apparently share them of his own volition.

About Ted Bundy, the Marilyn Monroe of true crime, everything is simultaneously true and not true. He murdered 36 women, or 100, or 365, like a fairy tale villain, depending on whose estimate you choose. He was genius who outwitted the police for years; he was a seething madman. He committed his first murder at 20, or 25, or 10. He battled his compulsions or he savored every minute of his crimes. The legal ethics attending Browne’s decision to write about his client’s confidences seem almost beside the point: Whatever he has to say has likely been said already, even if it has, in the past, been only a lucky guess.

In The Devil’s Defender, Browne describes Ted Bundy admitting to a lifelong obsession with “control,” and describing a childhood pastime in which he bought a few mice, took them into the woods, and began to “stare into the box and hold a hand over each one, deciding if that particular mouse would go free or die.” Browne describes Bundy confessing to the murders he had been publicly tied to, and admitting that, “when he was a teenager in Tacoma, he killed a fellow teenager, a male.”

“I did not ask any further questions,” Browne writes, “nor did he provide details except that the victim was approximately his age and the incident started as a sexual exploration game and turned deadly.”

Like the rest of America, John Henry Browne viewed his client with a combination of curiosity and disgust. As for the role he played in Ted Bundy’s life, he has the same questions many readers might have. “Does helping the devil make you a devil too?” he asks, in the memoir’s final pages. “While defending Ted Bundy, did I somehow absorb evil? … Is there something wrong with me that somehow makes it possible for me to defend evil?” About what, exactly, makes Ted Bundy so different from the rest of humanity, Browne marshals a “spontaneous” response he once gave on an afternoon talk show: “He lacked any notion that we are all somehow connected.”

If this universal connection does exist, then the field of criminal law is one of the few arenas where it exists in tangible form. The attorney is bound to his client, and can worship no higher god than the protection of his client’s interests. Whether a lawyer’s relationship with their client can allow them to understand the client more deeply than the public does is a thought-provoking question in its own right. It is a question that Browne poses, but the answers he hints at are familiar and pat: It is possible to absorb evil, he suggests, just as it is impossible to feel connected to evil without that connection hinting at an evil within us, and the only solution when we feel this connection is to get out while we can. The idea that this sense of connection, however personally troubling it may be, might also help us learn more about how a person can commit such crimes—and how others might be stopped from causing such harm in the future—appears foreign to Browne.

Polly Nelson, Ted Bundy’s post-conviction attorney and the author of 1994’s Defending the Devil, takes a very different approach to her subject. As a newly-minted attorney and a young woman meeting her client for the first time, Nelson describes no sense of darkness invading her psyche or evil compulsions seeping into her mind. Rather, she writes, she was highly conscious of her new client’s apparent discomfort.

“Ted seemed mortified that I had to be aware of the very circumstances that required my representation,” Nelson writes. “All his movements and conversation were designed to show me that he was not a monster, despite all documentary evidence to the contrary—which, by unspoken agreement, was never mentioned. But he knew that I knew, of course… It was my job to know.” In Nelson’s view, it was her job to know not just what her client did, but why. This is the kind of job that a defense attorney may accept or reject, but it is the only approach that can make revisiting such crimes a worthwhile undertaking.