Until recently, it was rare anyone had the gumption to make a fictional film about a sitting president. Primary Colors, the adaptation of Joe Klein’s 1996 book about Bill Clinton’s first presidential campaign, was lucky enough to arrive just in time for peak Monica Lewinsky in 1998. Oliver Stone’s tepid and underwhelming W. opened in late October 2008, weeks before Barack Obama defeated John McCain to succeed George W. Bush. But 2016 is proving to be the year that breaks all the rules, so here we are, in the final months of the Obama administration, presented with two different major motion pictures that dramatize opposite ends of the young Barack’s journey through the Reagan years: Vikram Gandhi’s Barry, which premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival and was recently acquired by Netflix, and Richard Tanne’s Southside With You.

Both films revolve around romantic developments in the young Obama’s life: While Southside meditates on a mixed-race youth’s bliss with his future wife, Barry is about romantic failure, the inability for love to bridge racial and class differences. To ask which film veers from the historical record in its rendering of the life and loves of young Mr. Obama is beside the point. But verisimilitude remains a lingering concern: While Tanne’s film presents two young people who will become the world’s most recognizable couple, Gandhi’s film invents a composite female foil for Obama who comes to represent the forces in American life that Obama will never quite win over, largely because of race.

Together, the two films form a bildungsroman unlike anything in American movies since John Ford’s 1939 film Young Mr. Lincoln, an elegant and oddly terrifying presidential hagiography—Cahier Du Cinema once argued that it was produced by Daryl Zanuck on behalf of “American Big Business” to mythologize the country’s most famous Republican and produce an election year defeat of FDR in 1940—that premiered seventy-five years after Lincoln’s death. No one has bothered to make a persuasive movie that focuses uniquely on the early life of Dwight Eisenhower or Gerald Ford, Jack Kennedy or Ronald Reagan, Jimmy Carter or George H.W. Bush. Most presidential biopics—like Spielberg’s Lincoln, HBO’s Truman and Rob Reiner’s upcoming LBJ—are firmly set during their subject’s respective Presidencies, long after the men in question are dead and buried. Barry and Southside With You are a curiosity in this context, positively rogue ventures with few precedents, acts of mass mythology that provide vastly different quasi-historical windows into the formation of Obama’s value system, presidential persona and basic understanding of the American promise through his attempts at coupledom.

Southside With You stakes out a charming inoffensiveness as its safe haven. Thirty-year-old Obama is working as a community organizer in Chicago in 1989. A legal intern with holes in the bottom of his car, he picks up Michelle Robinson, an associate at the firm, for a date: They go to a museum, for a walk in the park, and a screening of Do The Right Thing; in between he shows off his burgeoning political skills at a community event. Plenty of “wink wink, nod nod” moments unfurl. The tone is triumphant; we know the Obamas will work out, that their love will endure and that Barack, the son of a white, single mother, who never fit in much of anywhere, will find a union with a black woman that will be prove both emotionally satisfying for the characters and appropriate to his future constituents. Southside With You could have been written into the Democratic Party Platform itself.

The more melancholic, searching and insightful of the two films, Barry is the film we’re more likely to remember when the afterglow of the Obama presidency has long receded. While no less predictable in its conclusion than Southside With You, Barry proves to be a far richer and sobering experience, one that paints a portrait of a young Obama who painfully learns that regardless of what he says or how he says it, he’ll never truly win over the elite who run this country.

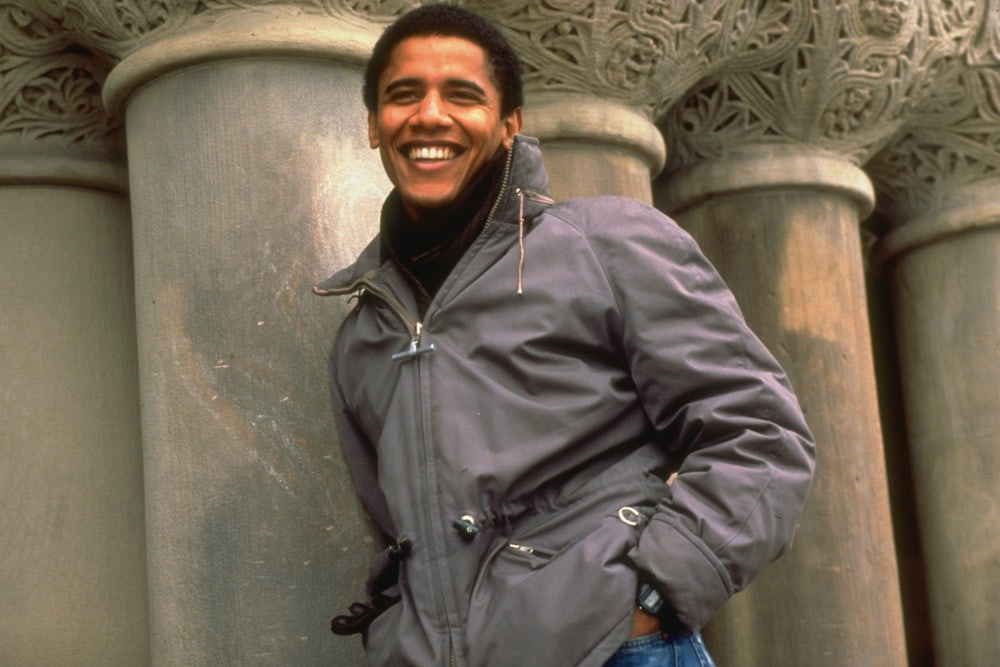

Set in 1981, it focuses on an afro’d, dope-smoking, poetry-obsessed twenty-year-old Obama, who has just transferred to Columbia University. With Adam Newport-Barra’s impressive lensing and Miles Michael’s spot on art direction, Barry inhabits a grimy, post-1970’s New York City much mythologized in our more sanitized era, from HBO’s Vinyl to Netflix’s celebrated The Get Down. Gandhi, a correspondent for HBO’s Vice News, is also a filmmaker of great versatility. A Columbia graduate himself—as an undergrad he lived next to the row house on 109th street Obama once resided in—he burst onto the scene with Kumare (2012), a fake documentary in which he tricked various expanded-consciousness-seeking whites into thinking he was an Indian guru.

Barry arrives in a grim, bottom’d out Manhattan during Reagan’s first year in the White House. Cigarette in hand, he reads a letter from his estranged father as he arrives on a flight from Hawaii during the opening credits. By the end of the sequence, he’s kicked off the campus for not having a student ID, locked out of his apartment, and is sleeping on the street. This is only the first of several rude awakenings for the future president. He and his roommate don’t have campus housing, so he settles into a crime-infested area south of the campus. His friend Saleem (Avi Nash) is the only person he knows in New York; Saleem is a drug-addled, well-off-but-hiding-it Pakistani student who speaks directly to Barrys radicalized malaise, that is, when he’s not shouting drunkenly out towards the street at negroes who are pillaging his garbage cans.

Barry features an affecting and affected performance by Devon Terrell, and in their electric scenes together, Terrell and Nash are two men of color who are comfortable with their sardonic pose of mild disaffection from the elite pale faces. But Saleem is all ironic hard edges where Barry still has some vulnerability. Informing Barry of how non-threatening he’ll have to sound to bed the rich white girls who are his only options for love in this rarified Ivy League environment, Saleem takes on a mocking “safe white dude” tone; a voice not dissimilar to the one a generation of black comics, aping Richard Pryor, have used to described the absurdity of being black in white America. The film almost suggests that Saleem has a more salient understanding of the crisis of the young black intellectual; but despite his brown skin, Saleem retains privileges of legacy Barry never will—his rich daddy with Wall Street connections can always bail him out. By the movie’s end, Obama’s father is dead.

Terrell, a young Australian actor, looks and sounds like Obama well enough, but he also shows us shades of the man we’ve never glimpsed in public before. He deftly introduces us to a college student who is still trying to figure out what he believes, what he wants to do, and what he’ll have to compromise to get there. At twenty, Barry has yet to figure out how to navigate the country’s great racial divide and—as we now know all too tragically in these stratified times—never will, despite great hope to the contrary.

Barry senses this and makes it plain. His romantic entanglement with Charlotte (Anya Taylor-Joy), a porcelain-faced Barnard brunette who comes from a well heeled Connecticut family tied deeply to the Democratic Party, draws out Barry’s budding realization that America is not designed for them to be together; no matter how hard he tries—despite a bloodline that links him to several of America’s earliest WASP clans—the good natured ignorance with which he’s treated in their environs, despite their best intentions, will never result in real solidarity.

“Pretty uptight people here, huh?” a bow-tie wearing white guy remarks to Barry at a wedding, which is held in a massive country mansion where Barry once again finds himself, other than the servants, the only black person in the room. “I’m an uptight kind of guy,” he replies, half-serious, half-empty. He knows he’ll never fully belong in these environs, but he finds it equally hard, no matter how “down” Charlotte is, to take her into black spaces. Buying books on the streets of Harlem, eating soul food at Sylvia’s, they are hounded with looks from stoic, stately black women, giving rise to Pryor’s contemporaneous observation that “sisters will look at you like you killed your mamma when you’re out with a white woman.” Seeing bellicose Black Hebrew Israelites in their outlandish costumes pontificate on a street corner wouldn’t normally be a point of concern for Barry, but he deftly steers Charlotte away in order to avoid a verbal scolding.

The costs of assimilation are high, and Barry begins to pay. He arrives on campus wanting to be a poet, as quaint as that sounds, but soon realizes the privilege of his situation beyond the iron gates of Morningside Heights. Playing basketball in a Harlem park, he befriends PJ (Jason Mitchell), a student from the Graham Projects who is finishing a master’s degree in business at Columbia. PJ has no illusions about what his degree is for: He is there to make money, to get the credentials America requires of negroes who want to advance into the middle class. Mitchell is every bit as terrific as he was in Straight Outta Compton, and often steals his scenes, including one where he invites Barry to a party in the projects. In a deft single tracking shot, we are introduced to the world of “pissy stairwells” and elevators that don’t work. “Don’t forget that this is how your country does your people,” Mitchell tells him. Barry is as foreign in this environment as he is later in the Yale Club with Charlotte’s parents. Here we see the political skills start to form as he charms them, emphasizing not his father’s drunkenness but his Harvard pedigree. Barry neglects to mention that Charlotte’s dad slipped him some money while in the men’s room before being introduced, thinking he was the washroom attendant.

Despite his ability to code-switch, Barry is haunted by confusion and pain; unable to cope with a father who abandoned him, and an inability—despite his insidious emotional intelligence—to feel at ease in all black or all white milieus. This costs him more than his fair share of acquaintances, friends, and most painfully, lovers. When Barry’s mother (Ashley Judd) arrives, he is embarrassed by her rah-rah liberalism and admits, in an unvarnished way he normally keeps buttoned up, how out of place he feels. Columbia’s classrooms are dominated by the kind of privileged blowhard who asks during a discussion of Plato’s Republic, “Why does everything have to be about slavery?” It’s a question the rest of the film answers by simply showing us how this black boy, no matter how yellow his skin, is treated by both working class white cops and rich, well-meaning white ladies alike. In the end, code-switching simply gets tiresome, no matter how talented you are, when white people seem to have no idea black people have to do it at all.

Obama’s last name is never heard in Barry—unlike Southside With You, it avoids casting obvious allusions to the present but is rife with moments that suggest multitudes. Instead, Barry is an intimate character study of the peculiar anxieties faced by middle class, mixed-race American men as the film industry has ever attempted: It would be groundbreaking even if it wasn’t about the future president of the United States.