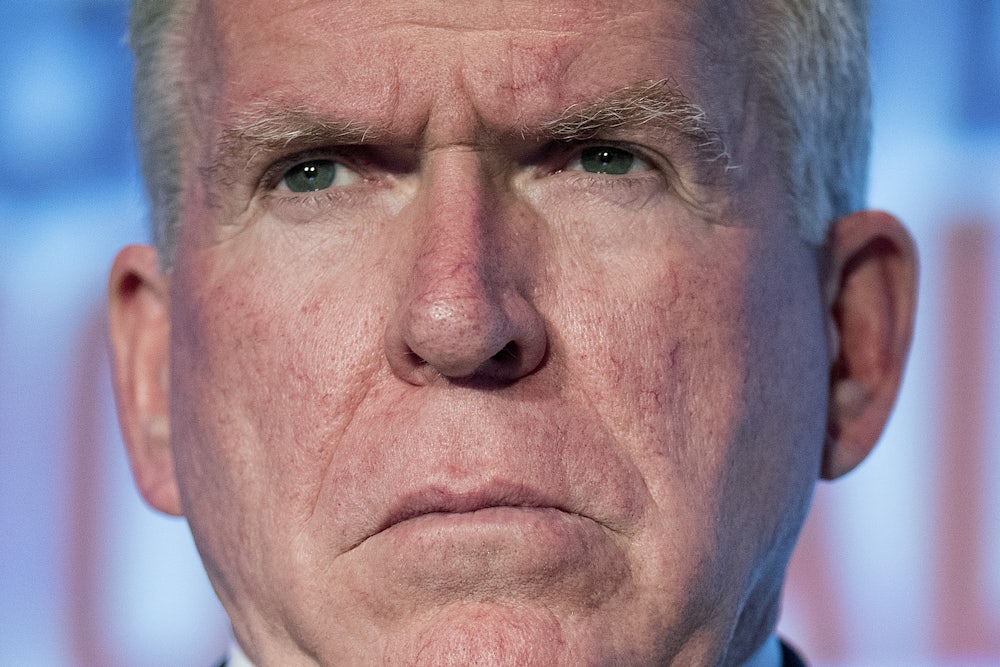

“The American people have the right to know the types of activities that their federal government performs on their behalf,” CIA Director John Brennan said on Tuesday at the Ethos and Practice of Intelligence Conference. It was the third annual installment of this CIA-sponsored confab, which was held at George Washington University’s Center for Cyber and Homeland Security and featured a buffet of intelligence insiders. Brennan opened the conference with a pious set of remarks about the value of the intel community, with a few civic-minded homilies thrown in for sweetener. Total secrecy “is no longer a feasible option,” he said; besides, it was “not reasonable” for democracies. “But this does not mean opening our doors wide,” Brennan cautioned, calling secrecy a “necessary element” for what intelligence professionals do, even as they must resist “secrecy for secrecy’s sake.”

It was a bewildering set of comments from a man who, according to an excellent recent series in The Guardian, helped suppress both Congress’ CIA torture report, which examined the Bush administration’s use of torture in the aftermath of 9/11, and the so-called Panetta Review, an internal investigation of the same practices. But Brennan’s dime-store philosophizing was just the opening soliloquy of a day of well-choreographed, perfectly dull theater. Proclaiming a need for “public debate about the issues facing our great nation and the world we live in, deeply complex and emotional issues, such as cyber and surveillance,” Brennan presided over a series of panels and lectures that would tell you nothing you couldn’t read, often with greater clarity, in The New York Times or The Washington Post. “As you can see from the panels’ makeup, we are not shying away from those differences of opinion,” he said, introducing a slate of past, present, and soon-to-be-again intelligence officials.

The vigorous debate that Brennan promised never materialized. Instead, through discussions of great power rivalries, disruptive technologies, humanitarian disaster, and the limits of secrecy, the various speakers presented mostly indistinguishable bromides about preserving American interests and maintaining national security. Most of the participants spoke in the same vacuous think-tank argot. The conference—with its overweening acronym, EPIC—managed to be a vivid example of a self-regarding security-state elite patting one another on the back for their shared accomplishments, while gesturing phonily toward the public they serve. It was all impeccably hashtagged and livestreamed and chronicled for posterity on the website of the Center for Cyber and Homeland Security (one of these strange, post-9/11 hybrid institutions that acts as a holding center for government officials between appointments). But if you couldn’t learn anything about what our 17 intelligence agencies actually do during this conference, you could at least learn something about how some government agencies have adopted the dubious ethic of “transparency,” which seems to boil down to running carefully stage-managed public-outreach events like this one.

The Ethos and Practice of Intelligence Conference is one in a growing list of public showcases for the intelligence community. No longer, as John Brennan noted, do agencies keep their very existences, as well as the identities of their directors, under wraps. “Transparency is here to stay for the intelligence community,” said Carrie Cordero, a former Justice Department lawyer. That may be true, but for Alex Younger, the head of the British Secret Intelligence Service who a couple decades earlier would have been known only as C, it was the first time he had spoken in public this year. And for many of Younger’s American colleagues, their comments were as opaque as the agencies they represent.

Chris Darby, who oversees In-Q-Tel, the CIA’s venture capital outfit, spoke of the need to “flux the threat space.” Speaking numinously about the “life force” of data and systems, Chris Inglis, former deputy director of the National Security Agency, offered a vision of the near future: “There are going to be fewer and fewer secrets, as physical phenomena and spoken words have fewer places to hide, as the sensors and analytic powers reveal all things—almost concurrent with the execution of those things.”

Besides these terrifying prophecies, there were a few moments of candor, if not genuine revelation. Darby lamented that commercial companies get data on a “granular level” that intelligence agencies aren’t legally allowed to collect. “These companies are intelligence agencies on their own,” he said. In another panel, Nick Warner, director-general of the Australian Secret Intelligence Service, talked about the ability of various state intelligence agencies to collaborate beyond the impositions of politics. “Oftentimes the security component of the country is the most influential,” Warner said. He then emphasized that he wasn’t in favor of military coups or non-democratic governance.

A few notes of dissent emerged on the day’s last panel, about public trust and oversight. The journalists Daniel Klaidman (Yahoo News) and Jason Leopold (Vice) presented the case for agencies like the CIA revealing more to the public. Leopold needled the panel’s moderator, CIA Deputy Director David Cohen, saying that the agency was “resistant to transparency,” that it sought to protect embarrassing information under the pretext of national security, and that a “cultural change” was needed in how the agency operated.

If Cohen was bothered in the slightest, he never showed it. Immediately after his panel, he gave the day’s closing remarks and proclaimed the conference a success. There was a clear diversity of opinion, he said: “Consensus was rare.”

If only that were true. An event designed to bridge the gap between the intelligence community and a rightfully suspicious public instead emphasized the depths of the chasm. For years now, the nation’s senior intelligence officials have been popping up at ideas forums, think-tank dinners, academic symposia, and the odd hacking conference. Like late-night talk shows, these comfortable redoubts form a well-oiled circuit for various security-state elites to press the flesh, push their initiatives, and reaffirm their commitment to being open with the public—all while interacting with a mostly pre-selected group of like-minded insiders. The effect is to promote “transparency” but of the most facile sort. As with the farcical oversight process—during which officials like Director of National Intelligence James Clapper can lie under oath, without consequence—these events pantomime democratic access and accountability.

But if the performance is convincing enough, perhaps its lack of substance doesn’t matter. Near the end of John Brennan’s discussion with intel chiefs from Britain, Australia, and Afghanistan, the topic of Edward Snowden came up. With strong public support for Snowden and a vigorous campaign underway to pardon him, one might think that the assembled braintrust might at least consider why a purported traitor is respected by many of his fellow citizens. Instead, the issue was brushed aside, as Australia’s Nick Warner had the final word: “All I can say is I’m amazed there’s still a debate about this in the U.S.,” he said. “Edward Snowden damaged your national security in very significant ways.” The crowd responded with hearty applause. The CIA director seemed pleased. “Well with that, I don’t want to ask another question,” Brennan said, before concluding the panel.