As the Revolutionary War entered its final days,

George Washington faced a military coup from

within his own ranks. The Newburgh Conspiracy,

named after the small town on the Hudson where

Washington made his headquarters after Yorktown,

was hatched by soldiers who had not been paid in years. If their demands were not met, they

declared in a letter, they would desert, leaving an

“ungrateful Country to defend itself.” On March 15,

1783, Washington quelled the uprising with a short but impassioned address. Appealing to their

“unexampled patriotism and patient virtue,” he

urged his troops to rise above “the pressure of the

most complicated sufferings.”

The sufferings of the City of Newburgh itself have been equally complicated. For years, it served as a bustling hub for trade between New York City and Albany. But when local industries began to fail, the city ignited in racial tensions. In 1961, Newburgh launched a series of discriminatory measures that required welfare recipients—most of them single black mothers—to line up at the police station to collect their benefits. (“No town ever got so famous so fast except for Little Rock,” remarked one resident.) During the 1970s, urban blight and thwarted plans for redevelopment sparked race riots and gang violence. In 2011, the media labeled Newburgh the “Murder Capital of New York.”

Washington’s headquarters are at the heart of Liberty Street, where the town’s revolutionary past collides with its impoverished present: Federal mansions and Victorian homes with gingerbread trim and big yards stand alongside derelict row houses with boarded-up windows. Today there are more than 800 vacant buildings in the City of Newburgh; on Liberty Street alone there are 62 vacant properties.

Vincent Cianni, who has lived in the area for nine years, has photographed the residents of the Liberty Street neighborhood for the past year with a large-format camera, often approaching people as they sit outside their homes. “As a former community activist, I was interested in the street because it runs the entire length of the city,” he says. “It covers a wide range of socioeconomic classes, from an upscale neighborhood with mansions in the north, to very distressed homes further south.” Most residents have lived on the street all their lives; others recently relocated from New York City. One longtime resident calls new arrivals the “forlorn hope,” a military term for the doomed first wave of soldiers sent into battle. To live on Liberty Street still requires the “patient virtue” urged by Washington—to rise, as he counseled, above the pressure of the city’s sufferings.

Washington was based in Newburgh during the final years of the Revolution; it was here he announced the “cessation of hostilities” with Great Britain on April 19, 1783. The building was made a National Historic Landmark in 1961—the same year Newburgh drew national attention for targeting black residents with discriminatory measures.

Today, Washington’s headquarters stand across the street from a pilates studio, a wine shop, and Mrs. Fairfax, a café named after a young love of the adolescent George.

Established in 1713, the Old Town Cemetery overlooks Liberty Street. Around 1,300 headstones survive today, with the earliest dating from 1759.

Longtime residents James Arline (center) with his two grandsons, Dion Drummond (left) and Antoine Drummon (right) in front of their house at 51 South Miller Street.

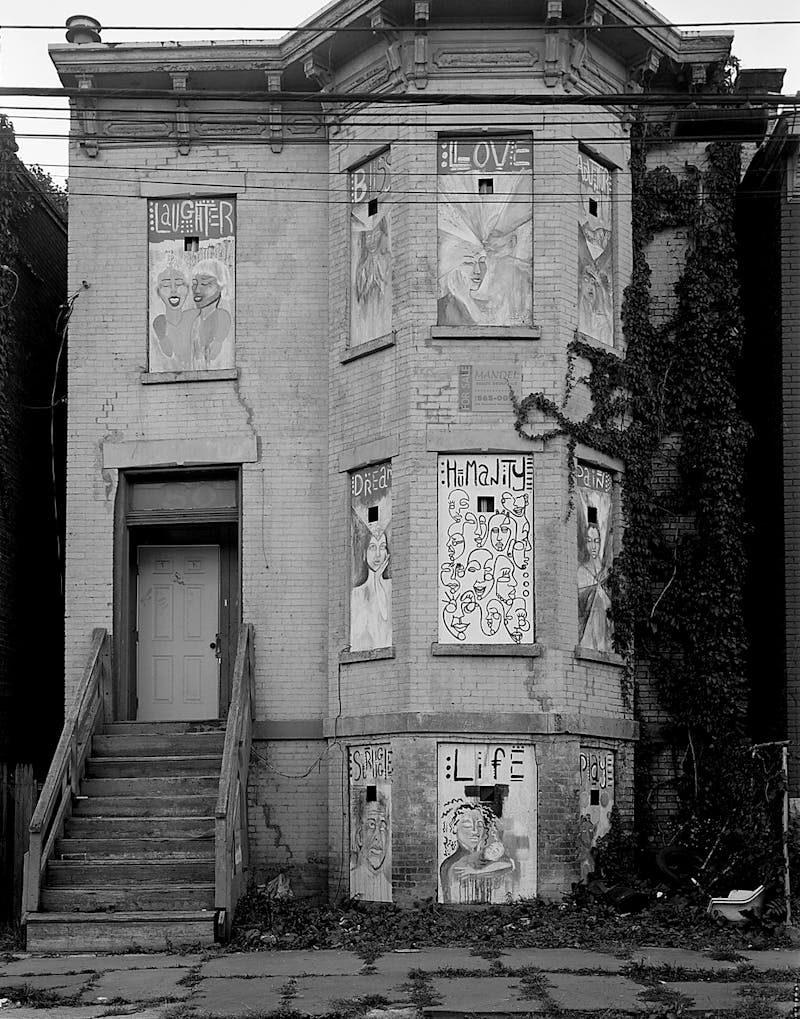

50 Lander Street is a Newburgh Community Land Bank property, part of a revitalization effort to redevelop distressed properties. In a failed attempt at urban renewal, the town demolished more than 1,300 buildings in the area during the 1970s and relocated residents to housing projects throughout the city.

Lifelong residents Janette Patrick, Yasia Boykin, and Mark Williams in front of a memorial to a neighbor. “I hope they build better schools, or something for the kids,” says Patrick. “So they have somewhere to go and can stay off the street.”

Patricia Salazar-Canigan and her son Tyrese in front of their home. Salazar-Canigan, a social worker, is a lifelong resident of Newburgh. She lives with her mother, children, and grandchildren. A third of the city’s households are headed by single mothers, and more than a third of families with children live in poverty.

Parts of Liberty Street are undergoing gentrification. Nadine Grey Speer and her boyfriend bought their home two years ago, after leaving Brooklyn. She hopes that the influx of new residents will bring jobs. “There needs to be more police and cameras” she says.

An abandoned building for sale. The fire department marks structures at risk of collapse with sign that has a white X on a red background. There are nine such signs on Liberty Street.

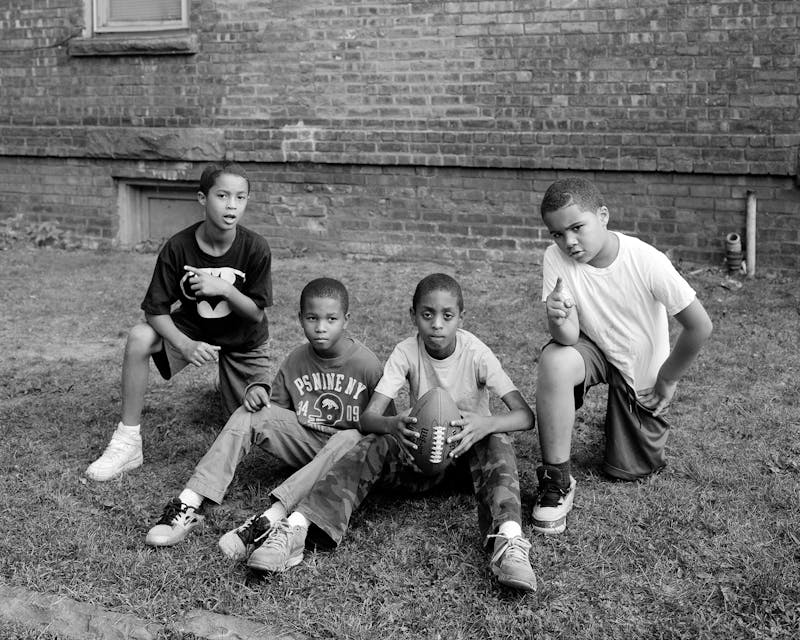

Neighborhood friends Jazier Hall, Zhamage Bailey, Ja-suy Lewis and Tajir Walker on the corner of Henry Street and Liberty Street.

A building on the corner of Lander Street and Courtney Street.