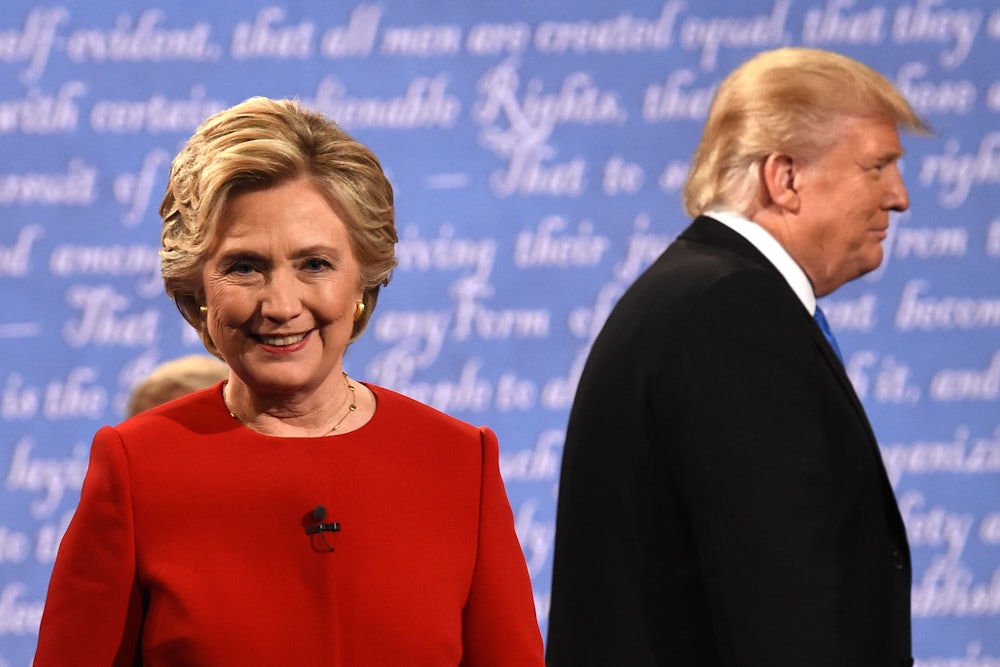

The easiest way to interpret this year’s third party insurgencies—their resiliency in polls, their appeal to some newspaper editorial boards—is to attribute their unusually strong showings to the historic unpopularity of the major party candidates, Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton.

This is practically a truism, but it’s also too generalized to provide an accurate sense of how the voting public views this election. A significant majority of voters, after all, believe that Trump, unlike Clinton, is unfit for the presidency. Attributing third-party strength this year to the fact that both candidates are unpopular requires collapsing that distinction, or assuming many third-party voters don’t consider the possible victory of an unfit candidate as an urgent threat.

A more nuanced picture emerges if you burrow down into the data, but one that still points to short-sighted thinking on the part of many Clinton skeptics. If she wins the election in November, as she’s forecasted to do, but only manages to eke out a narrow victory, which most forecasts suggest is likely, it will be partly because her vote margins are self-limited by a widespread assumption that she can’t lose.

Obviously people who don’t support and won’t vote for Clinton cite a variety of objections, some better than others. But some people clearly view Clinton’s persistent polling lead—Trump’s inability to overtake her in polling averages—as a kind of liberation. As long as she’s on course to win, some number of people who despise Trump, but don’t care for Clinton—millennials who believe she’s too corrupt or scripted; anti-Trump conservatives who can’t abide her liberalism; others laboring under a quarter century of hate debt—will feel freed to abstain from voting, or to register a protest vote for Green Party nominee Jill Stein or Libertarian Party nominee Gary Johnson. As YouGov pollster Will Jordan noted recently, 12 percent of Trump voters believe he’ll lose. Only three percent of Clinton voters have the same thought about her. By further contrast, only a tiny minority of third-party and undecided voters believe Trump will win. About half believe Clinton will.

12% of Trump vtrs support him & believe he'll lose. Only 3% for HRC. Only 15% of 3rdParty/undecided expect Trump win pic.twitter.com/W3P0mD4wkH

— Will Jordan (@williamjordann) September 15, 2016

The notion that the outcome of the election is in little doubt—that protest voting is a no-risk proposition—might ultimately prove to be more pronounced in states like California than in swing states like Florida and Ohio. But it is real. The editorial board of the Chicago Tribune embodied the phenomenon when it explained that “Republicans have nominated Donald Trump, a man not fit to be president of the United States…. Democrats have nominated Hillary Clinton, who, by contrast, is undeniably capable of leading the United States,” before throwing its endorsement to Johnson.

The nightmare scenario is that this turns into a runaway free-rider problem. If too many people assume Clinton has the election locked down, and use that assumption as their basis for not voting for her, she could lose. But even if the assumption is right—even if you’re a young progressive from California who believes with excellent reason that your vote won’t possibly be decisive—the Tribune’s line of thinking comes at a hefty price. This year the “lesser of two evils” rationale isn’t just an uninspiring appeal to risk aversion. It’s about making a positive and important statement to the world that in America, a racist authoritarian can not get within a hair’s breadth of the presidency—and that, if one happens to become a major party nominee, he will be defeated soundly.

Symbolism isn’t everything in politics, but in recent elections it has usually been the driving force behind third-party voting. Very few people in the country are truly ideological libertarians or green leftists. Likewise, many of the people who plan to vote for Johnson or Stein this year would probably reconsider if it appeared either of those candidates were likely to win.

If this were an election between Clinton and Johnson or Clinton and Stein, more people would learn that Johnson wants to abolish the income tax, or that Stein panders to anti-vaccine activists, and Clinton would suddenly start looking like an acceptable alternative. Young voters in particular are drawn to Johnson out of a sense that he’s more true-to-self than the scripted and secretive Clinton, even though her platform resembles young-voter priorities much more closely than his does.

For these very reasons, the notion of voting third party is often described as a way to make a statement or send a message. “We hope Johnson does well enough that Republicans and Democrats get the message,” the Tribune editors explained, suggesting a strong third-party showing in November will inspire the major parties to reassess their priorities ahead of 2020.

Johnson, it’s worth pointing out, will likely win zero electoral votes, even if he does unexpectedly well. The power of the “message” thus lies in the popular vote alone—in the number of people who support him across the country, whether they live in swing states or red states or blue states.

But if the popular vote is a good vehicle for a message, then we should ask: What’s the best message we can send with it?

One downside of the Tribune’s pox-on-both-houses argument is that if Johnson has a strong showing in November—say, 17 percent to Clinton’s 41 and Trump’s 40—that would send a message that a coin-toss between a fit and unfit candidate is an acceptable risk for the country. But the most important downside would be the opportunity cost of denying Trump the ass-kicking he deserves.

The Republican Party nominated an ignorant, bigoted, authoritarian candidate to be president of the United States. The best message that the country can send with the popular vote is that if you try to win the presidency by stoking race hatred and promising to degrade the Constitution, you will lose and lose badly—that a fascist does not have an even-odds chance of becoming the most powerful person in the world.

I’d argue this is a more critical and more responsive message than one that scolds Democrats for nominating a dynastic, uncharismatic standard-bearer. And it would be unmistakable, too. Just as nobody would really believe 17 percent of the country wants to elect a candidate who doesn’t know what Aleppo is, and can’t name a single foreign leader on the fly, nobody will treat a repudiation of Trumpism as a sudden groundswell of approval for Clinton. She will be given four years to dispel public doubts about her. Assuming Republicans don’t nominate Trump or one of his acolytes again in 2020, the cost of third-party voting will fall back down to where it was in 2012—still high in swing states, but very low elsewhere.

If you believe this election is basically a lock, or you happen not to live in a battleground, and are thus flirting with the idea of abstaining or of voting for a third party, ask yourself if you want to live in a country that has established proof of concept for a more polished racist demagogue. Do you want children growing up in a country where white supremacy has been re-normalized? Where misogyny doesn’t disqualify men for high office? Where erratic ignorance is placed in the running for the world’s highest award? Or would you rather send a message that if a major party nominates a fascist to be president of the United States—someone whose very character threatens national and global stability—the overwhelming majority of the country will flock to the candidate standing between him and the White House, and he will be left with the deplorables.