Pepe the Frog is all over the internet these days, usually in obnoxious or outright racist tweets by anonymous trolls of the alt-right—and sometimes by Donald Trump and his son. The fictional cartoon character has become an unofficial mascot of sorts for the Republican nominee’s campaign. As Vocativ reported Thursday, a group of Trump supporters in Pennsylvania has raised more than $5,000 to put up billboards showing Pepe (wearing Trump’s hair) guarding the border wall, with the message, “It’s always darkest before the Don...” The Hillary Clinton campaign has even felt compelled to explain that Pepe is a symbol of white supremacy and anti-Semitism, and the Anti-Defamation League has declared Pepe to be a hate symbol.

Pepe began as a benign symbol. Created in 2005 by cartoonist Matt Furie, who had no racist intent, the original Pepe was a slacker amphibian, a low-key dude at peace with the universe. His catchphrase was “feels good man,” taken from a comic strip in which he explains why he drops his pants all the way down when he pees standing up. For years Pepe was a popular, inoffensive internet meme. It was only in the last year or so that he was hijacked by hatemongers. The racist Pepe is in many ways an inversion of the original one. As Furie noted in an interview with The Atlantic, “The internet is basically encompassing some kind of mass consciousness, and Pepe, with his face, he’s got these large, expressive eyes with puffy eyelids and big rounded lips, I just think that people reinvent him in all these different ways, it’s kind of a blank slate.”

Still, it’s not entirely an accident that Pepe has been coopted in this way. For well over 100 years American artists, both racists and anti-racists, have found animal cartoons an effective way to make allegories about ethnic difference. Because direct discussions of racism are often fraught and divisive, anthropomorphism allows artists with good intentions to explore the issue indirectly. But as Pepe’s sinister turn shows, it also allows artists with racist intentions to be directly hateful.

Animal allegories are of ancient origin and exist in many cultures, but in the American context the decades after the Civil War were crucial. The white writer Joel Chandler Harris codified and popularized African-American and Native American folklore in his Uncle Remus stories. Br’er Rabbit, the trickster hero of Uncle Remus stories, was a fusion of characters found in both West African and Cherokee oral traditions. A hare who has to live by his wits in a world of predators, Br’er Rabbit has often been seen a metaphor for slaves. “Br’er Rabbit is a symbol of covert resistance to white power,” literary critic Robert Bone argued in 1975. “The trickster hero represents a represents a mode of resistance, not submission or accommodation.”

With the rise of the comic strip in the late nineteenth century, a new art form took up anthropomorphism, often borrowing from Harris’s massively popular work. The most important artist to use cartoon animals was George Herriman, a light-skinned African American who passed for white and created Krazy Kat in 1910. As biographer Michael Tisserand shows in his definitive forthcoming book Krazy, Herriman was born in 1880 in a vibrant mixed-race community in Louisiana, which his family had left behind with the rise of Jim Crow segregation in the late 1880s. In his public life, Herriman hid his identity, wearing hats to hide his kinky hair and explaining his olive skin with hints of exotic origins in Greece or France.

But in Krazy Kat, Herriman re-created the hybrid and pluralistic world of his youth, a cartoon utopia where there was no segregation and different species interacted freely. Set in shifting backgrounds of Coconino County (a real place in Arizona), Krazy Kat is about the eternal love triangle between a black cat, a white mouse, and a white dog. The title character Krazy Kat often shifts gender as well as color. In one of the last strips he did before he died in 1944, Herriman showed a brown weasel who paints himself white so he can buy insurance which is denied to dark-furred animals. The animal allegories of Krazy Kat allowed Herriman to make anti-racist statements that would’ve been taboo if made in more explicit form.

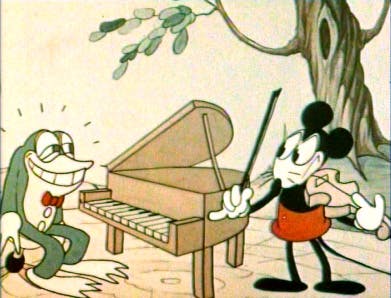

When Krazy Kat’s creator died, Walt Disney wrote to Herriman’s daughter that he was “a source of inspiration to thousands of artists.” Disney himself seems to have taken an important cue from Herriman in realizing that cartoon animals were a way of depicting ethnic pluralism, although the animator had far more conservative politics. Disney’s Mickey Mouse owes something to two of Herriman’s main characters, Krazy Kat and Ignatz Mouse, in having cultural traits that fused black and white culture.

As John Updike noted in his essay collection More Matter (1999),

Like America, Mickey has a lot of black blood. This fact was revealed to me in conversation with Saul Steinberg, who, in attempting to depict the racially mixed reality of New York streets for the super-sensitive and race-blind New Yorker of the 1960s and ‘70s, hit upon scribbling numerous Mickeys as a way of representing what was jauntily and scruffily and unignorably there. From just the way Mickey swings along in his classic, trademark pose, one three-fingered gloved hand held on high, he is jiving. Along with round black ears and yellow shoes, Mickey has soul. Looking back to such early animations as the Looney Toons’ Bosko and Honey series (1930-36) and the Arab figures in Disney’s own Mickey in Arabia in 1932, we see that blacks were drawn much like cartoon animals, with round button noses and great white eyes creating the double arch of the curious widow’s-peaked brows. Cartoon characters’ rubberiness, their jazziness, their cheerful buoyance and idleness all chimed with popular images of African Americans, already embodied in minstrel shows and in Joel Chandler Harris’s tales of Uncle Remus, which Disney was to make into an animated feature, Song of the South, in 1946.

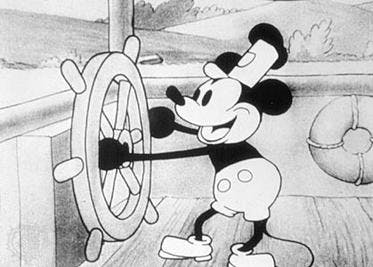

Mickey Mouse was in fact racially ambiguous, since he owed much to black culture but wasn’t seen as black by the audience, all the more so because as he became a corporate symbol Disney played down the black cultural references. By the 1950s, Mickey was a home-owning suburban rodent living in a white picket house. The 1927 Disney short Steamboat Willie, the first cartoon with sound, was inspired by Al Jolson’s The Jazz Singer—which is not surprising, since both Disney and Jolson (famous for his blackface) belong to the tradition of white artists who appropriated black culture and sold it to mass white audience. What got lost in the process was Herriman’s satirical intent. While Krazy Kat remains a powerful commentary on racism, one looks in vain for such commentary in most Disney cartoons.

Disney wasn’t the only cartoonist to draw inspiration from Herriman. Racial themes, often borrowed from minstrelsy, are pervasive in early twentieth-century cartoons. Apropos of the Pepe controversy, there was a strong tendency among cartoonists to associate frogs with stereotypical blackness. This is particularly evident in the character Flip the Frog, created in 1930 by Disney’s friend and sometimes collaborator Ub Iwerks. With his white gloves, red tie, and wide grin, Flip evoked blackface imagery. Similar minstrel frogs populated the 1937 MGM short cartoon “Swing Wedding” and the Warner Brothers classic “One Froggy Evening” (where Michigan J. Frog partly embodies nostalgia for the creativity of Tin Pan Alley music, which was predominantly played by African Americans). The most recent example of this tradition is the 2009 Disney feature The Princess and the Frog, whose main characters are African-Americans living in George Herriman’s hometown of New Orleans.

Jim Henson was surely aware of this tradition when he created his most famous muppet, Kermit the Frog, whose signature song is a melancholy reflection on racial shame, “Bein’ Green” (written by Joe Raposo). “It’s not that easy being green,” the song begins, and later laments, “It seems you blend in with so many other ordinary things. And people tend to pass you over ’cause you’re not standing out like flashy sparkles in the water or stars in the sky.” But it ends with acceptance: “When green is all there is to be, it could make you wonder why. But why wonder? Why wonder? I am green and it’ll do fine. It’s beautiful! And I think it’s what I want to be.”

When the alt-right kidnapped Pepe the Frog, they weren’t just seizing control of Matt Furie’s character, but also defiling an entire artistic tradition of using animal allegories to comment on racism. They were returning cartoon animals to the crudity of blackface creations like Flip the Frog and denying the artistic depth found in works ranging from Krazy Kat to the Muppets to Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel Maus (where the cats are Nazis and the mice Jews). Pepe the Frog, as perverted by its captors, is a kind of inverted Kermit: a frog drained of any humanity.

Yet what is stolen can be returned to its rightful owners. Furie has given his imprimatur to a “Make Pepe Great Again” movement, which denounces the alt-right theft and encourages the meme-ification of non-racist Pepe cartoons. Meanwhile, Talking Points Memo founder Josh Marshall has called for a renewed appreciation of the “canonical pluralism frog” Kermit, leading many to adopt Kermit as their Twitter avatar. In all likelihood, the alt-right kidnapping of Pepe will be remembered as simply a passing fad, much less significant than the brilliant tradition it shallowly mimicked. But that may depend on whether voters reject the man whom the frog has come to represent.