The precarious state of Phil Collins’s heart was one of the great pop concerns of the late twentieth century. Is it broken? (“How many heartaches must I stand / Before I find the love to let me live again”) Is it better now? (“Two hearts, believing in just one mind / Beating together till the end of time”) Did someone break it again? (“There goes my heart again / Tearing and breaking down”)

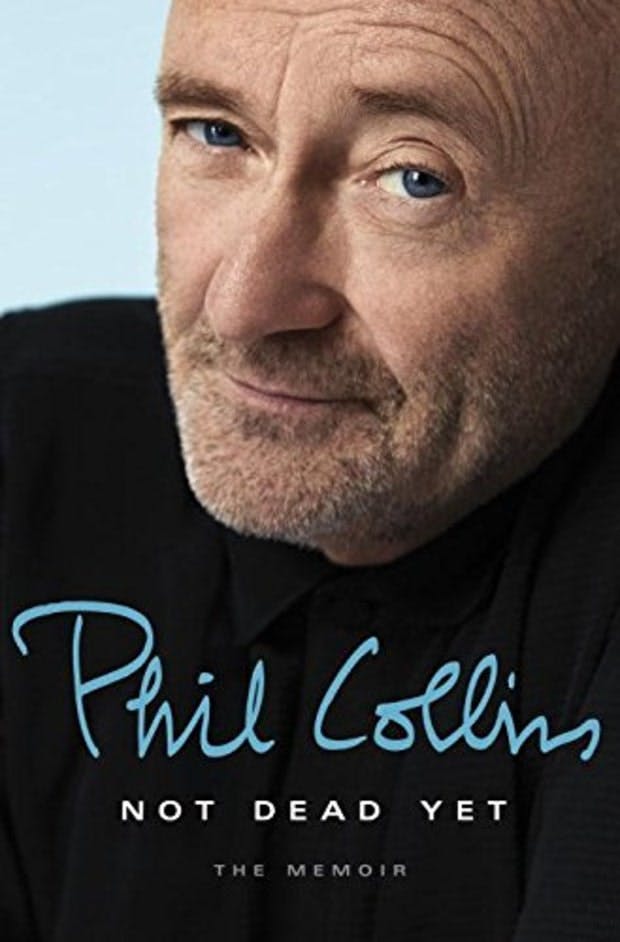

Collins was just seventeen when he wrote his first pop hit, “Lying, Crying, Dying.” It was the kind of song you might expect from any lovesick teenager. In it, he pleads, “Would you laugh in my face / and just turn and walk away?” Now 65, looking back on a life of platinum hits in his recently released memoir Not Dead Yet, it’s clear Collins never quite outgrew the bombastic emotion of young love. “I enjoy dwelling on matters of melancholy,” he writes.

Collins’s songs were engineered to deliver sentimental pop hits to a generation of men with Peter Pan syndrome. The broken-hearted ballads he wrote as the front man for Genesis catered to those who needed to protect themselves from destructive, careless women. In Collins’s hands, love is the heart itself, ripped out and passed around—the body is rendered obsolete (“Take a look at me now, oh, there’s just an empty space,” he sings in 1984’s “Against All Odds.”) The songs were tailor-made for post-war Boomers, ideally played in a convertible with the top down. It was the kind of music that appealed to the aspirational and insecure. Patrick Bateman, the ax-wielding yuppie murderer of Bret Easton Ellis’s 1991 novel American Psycho, raves about Genesis: “Has the negative impact of divorce ever been rendered in more intimate terms by a rock ‘n’ roll group?”

Phil Collins joined Genesis as its drummer in August 1970, when he was nineteen years old, playing for an audience much like himself, “mostly male, mostly hairy, mostly students.” During this heady decade, Genesis’s prog rock would contend with the rumblings of punk music in England and hip-hop in the U.S. But when Genesis made America part of their 1973 Selling England by the Pound tour, replacing the traditional road van with two white stretch limousines, the path to pop superstardom was still unfettered for nice white men.

After six years behind the drums, Collins became the lead singer of the band in 1976, when Peter Gabriel launched his solo career. Their third release, And Then There Were Three, was a marked shift toward a more commercial, less conceptual sound. “Follow You, Follow Me,” was a breakout hit, as an earnest Collins sang, “I will stay with you, will you stay with me / Just one single tear in each passing year.” The song was a soft rock tribute to love and devotion, and it has become a staple at weddings. An ambitious Collins wanted to break Genesis out of its prog-rock roots and aim straight for the anesthetized heart of pop music worldwide—the album went gold, and then platinum. After the release of Duke in 1980, he writes, “I will hold my hands up and admit that, with all the success, it’s quite possible that I have been giving off an unintentional smugness.”

Throughout the 1980s, the Collins was the embodiment of empty pop music embraced by upwardly mobile white men. His joyful songs were “bright, white-R&B” that was engineered to make you “feel so good,” even if the lyrics didn’t exactly make sense. (“Sussudio” was based around a sound he made up while improvising with a drum machine.) His sad songs were mainly about heartbreak and were often personal, although the lyrics were often vague: “In the Air Tonight” famously recounted the bitter 1980 divorce with his first wife, Andrea Bertorelli: “Wipe off that grin / I know where you’ve been / it’s all been a pack of lies” as the guitar shudders behind him. (Collins would eventually amass three ex-wives, and thus plenty of fodder for his songwriting.) “I don’t seem to be reaching her,” he writes. “So I communicate in song. When Andy hears these words, she will realize how fucking hurt I am, and how much I love her, and how much I miss my kids, then she’ll understand. Then it’ll be okay.” It wasn’t. Bertorelli later told the Daily Mail: “Our marriage broke down for many different reasons, the main one being his short fuse and preference for arguing instead of discussing anything we disagreed on. He would rage a lot and I felt like I was being bullied.”

Even if Collins’s songs weren’t getting through to his wife, they were winning over audiences worldwide. When Invisible Touch broke in 1986, the title song was seemingly everywhere. It is still band’s best-selling album, but the reviews were mixed. Invisible Touch could almost pass as outtakes from No Jacket Required,” writes Daniel Brogan in the Chicago Tribune, referencing Collins’ third solo album, wondering, “Will the Free World ever tire of Phil Collins?”

Apparently not. Genesis’s intellectual prog rock had given way to a playful populism—art-house meaning replaced with the joyful and absurd. The treble-heavy chart-topper “Don’t Lose My Number,” was pure kitsch, its lyrics maddingly vague, as if Collins had written them on a napkin and then proceeded to mop up a drink. Collins was aware that his songs were largely about nothing, as evidenced by the video for the hit, which included Goofy Phil as a samurai warrior, and earlier, as a Gene Wilder-esque fellow in a white suit on a beach. At stadium shows he often wore a mechanic’s jumpsuit—a far cry from Peter Gabriel’s fox head and dress in the early days of Genesis. Collins was, at times, into swelling orchestral sounds and peppy horns, but only in moderation. He seems to have somehow missed the coke binge of the 1980s, and all of its interesting excesses. “I’m the breadwinner, the provider, and I need to go out and work my family,” he writes. “Not to buy a guitar-shaped swimming pool or a champagne-colored Rolls-Royce. Just because, quite simply, it’s my responsibility.”

Collins’s was the music of overwhelming success for the generation of the overwhelmingly successful, before the 1987 financial crash swept it all away. His music reflected the precarity and responsibilities of the everyman during this time, although his songs are rarely political. In 1981’s “Man on the Corner,” for instance, he sings about a “lonely man” on the street and identifies with him: “Nobody knows him, and nobody cares / Cause there’s no hidin’ place / There’s no hidin’ place / For you and me.”

Take apart any Phil Collins song and you have on your hands an unfettered mess of synthesizers and male pain. Whether he liked it or not, Collins embodied this type of “white man’s pop,” even though his music wasn’t about money, or even success. Rather, it chronicled his failures in love, and the creeping feeling of not fitting in, despite the millions of records sold. It was music for a generation of men who wanted to climb the corporate ladder and not get led astray by a deceitful woman, but who also yearned to find home in an available body. “She’s an easy lover,” he sings in “Easy Lover,” continuing, “She’ll take your heart but you won’t feel it…” In Collins music there is little emotional depth, just an attempt at pathos, followed by a synthetic drum fill. It is music about women, not for them.

“It’s a frustrating, enraging situation—one that, alas, won’t be ending anytime soon—but also an inspiring one,” he writes about the dissolution of his second marriage, which results in his second studio album Hello, I Must Be Going! “The last thing I want to do is make a second divorce album,” he claims, “but being someone who writes from the heart and not the head…I have no option.”

This type of white male insecurity, coupled with entitlement and ambition, is precisely the pop man’s burden. During his rise to stardom, Collins was acting under the impression that his experience is universal. And yet, he continually shies away from a close read of his work. “Forced at gunpoint to analyze it, I’d have to say it’s a good break-up song, with universal resonance and empathy,” he reluctantly writes about the song, “Against All Odds.” All he can muster is: “People hate a break-up, but they love a break up song.” The women in his songs act as a foil against which he can project his own fears and insecurities. (Beyond his lack of sensitivity toward women—who remain the “invisible touch” he craves—Collins and his band were also not known for tactfulness toward minorities. In the video for 1983’s “Illegal Alien,” for instance, Collins sports a large fake moustache, a mussed-up black toupee, and a five o’clock shadow; he appears to be attempting to sing with a Spanish accent. The chorus is simply, “It’s no fun / being an illegal alien.”)

Phil Collins ruled the charts in a rapidly changing era, when pop was battling for youthful attention with punk, disco, and hip hop; his compatriots were Lionel Richie, Billie Joel, and Eric Clapton—singer-songwriters influenced by R&B, but who stayed clear of its vocal excesses. Twenty-five years after American Psycho lampooned Collins, we are living in a post-white man’s world of pop. The perennial themes are the same—broken relationships, anger, yearning—but the women with the “invisible touch” have taken over, crushing Collins just as he feared they would. Where the pop man’s burden was to present thwarted desire through the lens of male heterosexuality, pop music today more often focuses on female empowerment and individual growth. “You say sorry just for show / If you live like that, you live with ghosts,” Taylor Swift sings in “Bad Blood,” from 1989, while Adele coolly croons, “Send my love to your new lover / Treat her better…” on 25. Adele’s soul-baring 21 currently stands at number one on Billboard’s top 200 albums of all time, and Beyoncé’s genre-spanning “journey of self-knowledge and healing,” Lemonade, is the most talked about album of the year.

The pasty-faced singer became an easy target for critics. “It’s hardly surprising that people grew to hate me,” Collins told FHM in 2011, as he looked back on the arc of his wildly successful career, and saw that the public was reaching a saturation point with music that sounded the same, covered the same themes, and never really grew up. “There are cab drivers who radiate more natural magnetism and charisma,” writes one critic, while another lamented that our aged and balding friend Phil has become “stiff, sequenced, and safe.” Another disgruntled listener notes, “[His] songs are like an aural equivalent of hand sanitizer.” Even a fan concedes that he looks “somewhat like your gym teacher, minus the whistle.” Collins had none of the weird allure of Peter Gabriel; even Paul Simon has managed to retain a certain coolness Collins could never catch. In the ultimate dismissal, David Bowie, when questioned about his ‘80s output, refers to it as his “Phil Collins years.” Years after Genesis had broken up, the consensus had hardened. When a 1987 Wembley Stadium concert was released sixteen years later, one critic begged for mercy. “Have we suffered enough yet?”

In the early 2000s, Collins’s music became a tabula rasa for a growing number of rappers to explore their own vision, buttressed by the easy appeal of ‘80s pop kitsch. Looking back on the boost in the memoir, he boasts that “my approval ratings in the hip hop community are particularly high.” This is partially correct, although it may sound Trumpian in its claim. In 2001, Lil’ Kim even did a truly bizarre version of “In the Air Tonight,” where the MC yells at the beginning, “It ain’t gonna make no sense what’s about to happen here!” Seven years later, Kanye West didn’t hesitate to tell Miss Info, “I’m trying to put on those Phil Collins melodies,” which he did in 808s & Heartbreak, if you’re talking about the drum fills. This fall, the 24-year-old Atlanta rapper OG Maco released his Blvk Phil Collins EP, which sounds very little like anything Collins would produce, but the aura is there, apparently. “Who was able to craft emotion in sound into one soundscape, one experience in every song?” he queries in a video. “Nobody better on that shit than Phil Collins…His struggle could be felt by anybody.”

This idea of striving, of wanting to be appreciated by everyone, and of getting respect from people who have been denying your gifts, seeps through the memoir. “I’m not chasing another Top of the Pops slot of craving another zero in my bank balance,” he writes. “Robert, Eric, John, Philip, Frida” [referring to Robert Plant, of Led Zeppelin, Eric Clapton, John Martyn, Philip Bailey of Earth, Wind & Fire, and Anni-Frid “Frida” Lyngstad of Abba] “these are people I’ve grown up with, people I’m fans of, and/or people who look great in a fur coat. People I class as icons and true artists. Working with them is an honor.” In the book, Collins emphasizes both his ability to create “another project, another single, another inescapable Phil Collins hit,” and the fact that he was constantly in-demand by high-profile group of musicians. It’s an ouroboros that he never wants to end.

But eventually, his age, and his persistent lack of confidence, catches up with him. In 2011, following a series of health problems, a bout with alcoholism to “numb the pain,” and his third divorce, Collins officially retired from pop music. “I don’t think anyone’s going to miss me,” he relayed to FHM. “I look at the MTV Music Awards and I think, ‘I can’t be in the same business as this.’” That year, Katy Perry won Video of the Year for “Firework,” Beyoncé won Best Choreography for “Run the World (Girls),” Britney Spears won Best Pop Video for “Till the World Ends,” and Lady Gaga won Best Video with a Message for her synth homage to queer youth, “Born this Way.” These singers had beat Collins at his own game, taking the raw, emotive aspects of his pop sensibility, but personalizing it in a way he could never feel comfortable with. In the memoir, he describes meeting Adele for the first time in 2013 when she was writing her album 25. “I make her a cup of tea and try to hide the shiver of nerves,” he writes. “I feel like I’m being auditioned, but that’s my insecurity.”