If you had to picture a single animal as the face of climate change, more likely than not a polar bear would swim through your mind. This isn’t exactly a coincidence: It’s the result of a carefully planned political campaign. In the mid-2000s, the Center for Biological Diversity and other environmental groups were putting pressure on the Bush administration to act on climate change. Their strategy was to get the polar bear protected under the Endangered Species Act, listing global warming as their cause of endangerment. This would, in theory, require the government to address warming temperatures since, under the law, they had to deal with the cause of the bears’ decline. The activists knew the government would try to stall, so they chose an animal that could take the public stage, garner support, and compel the government to act. The polar bear, in all its massive soft-white glory, became their star.

As it turns out, polar bears are insanely cute, and no one wants to be responsible for their demise. Pictures of bears on melting ice floes flooded the internet. Children wrote letters to elected officials, begging them to save the polar bears. At the apex of this obsession, a polar bear named Knut was born in the Berlin Zoo in 2006 and abandoned by his mother, a former East German circus bear named Tosca. Hand-raised by humans, Knut’s survival hung in the balance, much like his species’ larger fate. This, in part, fed the ensuing “Knutmania.” Thousands of people lined up outside the zoo every day just to catch a glimpse of the little bear. The cub was even photographed by Annie Leibovitz and featured on the cover of Vanity Fair’s “green issue” alongside a scowling Leonardo DiCaprio. No single bear bore the weight of as much human attention as Knut.

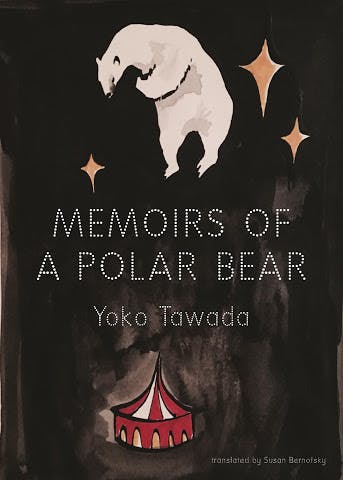

Knut was the real-life inspiration for Yoko Tawada’s Memoirs of a Polar Bear, a novel originally published in German in 2014 and whose English translation will be out this November. In the book, a cub named Knut is one of a family of performing bears, who are all, in magical realist fashion, gifted with high doses of literary ability. Knut’s narrative is the final part of Memoirs, which first follows the stories of his mother Tosca and her unnamed mother, a polar bear who accidentally writes a best-selling autobiography called Thunderous Applause for my Tears. (The book is titled by her publicist, a choice that irritates her since it is part of her “physical constitution to be incapable of tears”).

Memoirs gives us an often funny and intimate perspective on what it must be like to be a sentient bear in an overwhelmingly human world. Take, for example, Knut’s grandmother, who unwittingly gets in a fight with a group of neo-Nazis, but mistakes the swastikas on their jackets for Red Cross symbols—“I was horrified,” she writes. “Had I beaten up a team of Red Cross workers?” Or, another time, when someone tries to make small talk about the weather with her, she thinks to herself, “It isn’t good to talk so much about the weather—weather is a highly personal matter, and communication on the subject inevitably fails.” The book also forces its readers to confront Knut’s intense popularity through his perspective. “The little bear began to enjoy this divine omnipotence,” Tawada writes of Knut’s daily frolics in front of zoo-goers with his keeper, Matthias (which Knut terms “public service”). “The ebb and flow of the audience’s excitement was in his hands.”

The daily life of the polar bear, a species burdened with leading the charge against the destruction of their planet, has become a sort of performance in and of itself. Take, for example, the photo of an emaciated polar bear that went viral on Facebook last year or the numerous live polar bear webcams set up in zoos and tundras. Of course, in a twist worthy of Black Mirror, their audience also happens to be the same species responsible for their demise. Tawada just makes this conceit more literal, by casting her bears as actual artists in one way or another. Tawada’s Knut, who is as inquisitive as he is empathic, aptly grasps the semi-ridiculous symbolism of his own life: “If I had died, the greenhouse gasses in the sky would have formed a giant, steel-hard layer that would have lowered itself upon the city like a lid on a pot … but because the miracle worker Matthias had succeeded in making milk flow from his fingertips to feed the wunderkind, the North Pole was saved and thus the rest of the world as well.”

The bears in Tawada’s book all long, in some way or another, for the North Pole, a homeland they have never even seen before—while Knut waits for winter to come in Berlin, he begins to dream of it: “The North Pole had to be as sweet and nourishing as mother’s milk.” In another scene, Knut’s grandmother imagines herself standing on a melting ice floe. “This ice island is still as large as my desk, but eventually it will no longer be there. How much longer do I have?” In these moments, Memoirs seems to ask: What will become of the animals who may soon only live as displaced beings in a world that was once their home?

Knut and his forebears have each integrated into European society, albeit only somewhat successfully (“Minorities are fabulous!” a woman says to Knut’s grandmother on a train to West Berlin). There is one scene that captures the absurdity of the situation that the polar bears have found themselves in: Knut’s grandmother decides to switch from writing in Russian to learning how to write in German in order to take control over translations of her work. Her publicists angrily tell her, “Write in your own language,” to which she replies, “My own language? I don’t know which language that is. Probably one of the North Pole languages.” Like many migrants, Knut’s grandmother is ascribed an identity and demanded to stay within its confines. But of course, all European languages are foreign to a bear.

The animals are also uncomfortably aware that the value of their existence is linked to their supposed cuteness. During one of his walks around the zoo, a panda says to Knut, “You’re pretty cute. But don’t let your guard down! It’s the animals who look the cutest that are dying out.” The panda theorizes that those species who are closest to extinction are evolving to look cuter in order to play upon humans’ protective instincts. Near the end of book, Knut begins to lose his popularity as he grows into a more threatening adolescent. Some days, his enclosure only gets a single visitor. This, of course, is the particular hardship of a species whose existence depends on the fleeting attention of humans. As Jon Mooallem, the author of Wild Ones, has noted, “the polar bear has lost a lot of its cachet” over the last few years. He points to a 2013 video on climate change put out by the White House that doesn’t include a single image of a polar bear. In 2011, the real-life Knut had a seizure and drowned in the pool in his enclosure. He was only four years old when he died.

In the late 20th century, Ursula Böttcher, an animal trainer for an East German circus, captivated the world travelling around with her polar bear routine, which could involve up to eleven bears on stage at once. The act’s highlight was its gut-wrenching finale, which was aptly named the Todekuss or the Kiss of Death. Böttcher, who was only five feet tall with blonde curly hair, would hold up a sugar cube and present it to the crowd as the band switched from an up-beat four-four time to an expectant drum roll. She placed the sugar cube in her mouth and tilted her chin up, while a polar bear, who towered at nearly twice her height, would amble over on her hind legs, bend down, and delicately snatch the sugar from Böttcher’s mouth.

Memoirs borrows from this performance (Böttcher’s troupe included the real-life Tosca). In the book, Tosca waxes fondly on her time traveling around the world, performing the act with her trainer, Barbara. She provides for us a “bear’s-eye-view” of the kiss:

I stand on my two legs, my back slightly rounded, my shoulders relaxed. The tiny, adorable human woman standing before me smells sweet as honey. Very slowly, I move my face toward her blue eyes, she places a sugar cube on her short little tongue and holds up her mouth to me. I see the sugar gleaming in the cave of her mouth. Its color reminds me of snow, and I am filled with longing for the far-off North Pole. Then I insert my tongue efficiently but cautiously between the blood-red human lips and extract the radiant lump of sugar.

Looking back at the video of the real-life Kiss of Death, it is striking that in comparison to the rest of the act, which filled the stage with bears jumping through fire and balancing on bright blue balls, the finale is actually quite simple. But it isn’t hard to see why it was the routine that brought Böttcher to fame. At that moment, she and the bear are on equal footing. And, for a second, the two of them standing on stage together, occupying the same space, the same planet—it seems like the most natural thing in the world.