It was my wife’s idea that I should dress up as Donald Trump for Halloween. She’d be Hillary Clinton and, though I am a Clinton supporter, my wife had the optimistic idea that together we’d portray political comity on the cusp of this most polarizing presidential election. It was also to be in the tradition of staged, costumed political satire like Henry Fielding’s eighteenth-century British send-up of the Walpole administration, The Tragedy of Tragedies, or, The Life and Death of Tom Thumb the Great.

But it turns out fake reality on the ground in America is different. That’s why this year, the holiday has stuck with me since it passed—an ongoing event that has refused to recede, instead conflating with another holiday, Election Day, and defining our big and singular American moment.

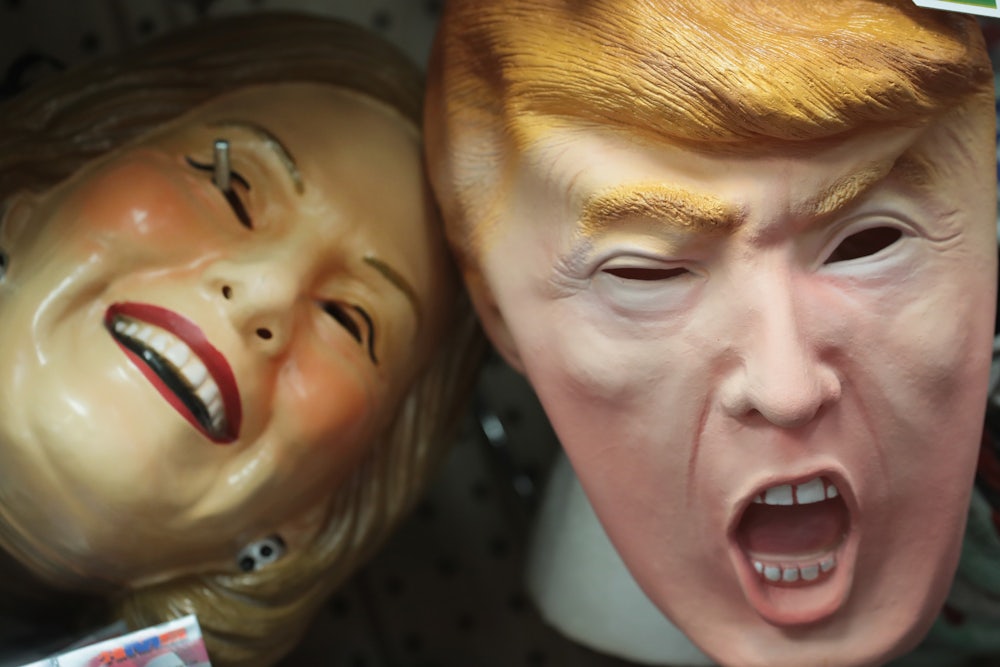

My wife had ordered me a “Mr. Billionaire Wig,” a tousled toupee the color of cheap champagne, and acquired some pumpkin-orange face paint. Then, the Saturday before Halloween, she announced she’d been so busy sewing the ghost and pink unicorn outfits our children had requested that there was no time left for a pantsuit. She would again wear the chicken outfit she’d made last year. I was a political rooster out on my own.

In New Haven, where I grew up and now live near, Halloween is serious. People thinking about real estate describe virtue in streets that are “good for trick or treating.” The Sunday morning before Halloween there is a children’s parade on the west side of the city. Then, on the night itself, residents from surrounding communities converge on East Rock, a densely settled neighborhood populated by many liberal professionals and university employees. It’s a Democratic city in a blue state, but around town and just outside you can find a diversity of opinion—and signage.

On Sunday I put on a white shirt, red tie, suit coat, stuffed a large pillow under the shirt, and slid into the front jacket breast pocket a little card with “BIGLY” written on it. Then came the hair and the face paint; I was ready for the hustings. Truth be told, it had been a busy week and I hadn’t really thought about what it might feel like to impersonate such a divisive figure as Trump. Many people across the country were dressing up as one of the candidates. It was just this year’s benign costume.

Except maybe not. The Chicken would meet us afterwards, so I marched alone with the ghost and pink unicorn in the parade, and as soon as I began walking there was the discomfiting feeling that onlookers didn’t know how to take this. Westville has a substantial population of older left-progressives. As I guided the kids across intersections, passing by people whose appearance suggested a kinship with Ben and Jerry, there were hard looks. But I sensed similar hostility from the middle-aged white dudes lounging around a pickup truck. All the way along, I had the impression that there was indecision about whether I was celebrating Trump or mocking him, and it seemed to me the default was to feel I was against them.

The parade ended in a park, and for a while I happened to stand by a stone wall. Now that I was stationary, there was abundant commentary. People would spot me and yell out “Hey, Trump!” or “It’s Trump!” There was the assumption that I’d offer up Trumpisms in return, and I called out “Wrong!” or “Huge!” or “Disgusting!” or “Low energy!” or “Only little people pay their taxes!” That I was beside a wall was further provocation, prompting references to “Your wall.” It was pleasurable to say “millions” and “billions” with that particular Trump inflection, and it was initially fun to make strangers laugh by telling them they were “Very, very sad puppets.”

I never crossed over into the sexual harassment realm—faked or not, I couldn’t go there. But it quickly became apparent that, as Trump, I could say just about anything—“You’re a terribly overrated and horrible loser!”—and people would smile and genially lob similar insults in return. I was expected to do the unacceptable; the mere presence of the persona gave license for the sort of uninhibited language most of us would normally suppress.

This, I thought, is what some people mean when they applaud Trump for saying what he thinks, for speaking exactly what’s on his mind. A lot of Americans want to voice their raw opinions, and they resent the social norms that demand restraint. Hence, the cacophony of racist and sexual and anti-Semitic insults at Trump rallies. I also thought about what Halloween is, the holiday when people take on the guise of something other, put aside the filters of deliberation, and get to be impetuous, visceral, transgressive, scary, and orange. Only this year, when our annual permissive-aggressive evening has morphed with the political season, Halloween had suddenly become more potent.

All presidential nominees spend the late stages of the campaign twisting and contorting to appeal to a vast country of voters. Usually, the game is not to bend yourself too far, to reassure people that in the end you have humane values and core beliefs, that you stand for something, that you can be trusted. Yet by behaving like a Halloween character and saying virtually anything he pleases, Donald Trump has undeniably touched something deep in the American grain.

Part of why both Halloween and the rituals of election season are so popular is that America is the country built on a myth of self-reinvention: all of our votes are equal, so we all can be anybody we want to be. But that’s a story we like to tell ourselves, because the myth is only true for some Americans. Trump’s is the story of a brilliant self-reinventer. He’s been allowed to dress up as many things across his fascinating life. That there may be far less there than he claims (in the bank and otherwise) is part of his genius, and his privilege.

Among the reasons you don’t want a Halloween character to be your president is that in real life people who think or otherwise seem different become unprotected and vulnerable. It may be that our current impulsive, headlong climate has something to do with an F.B.I. director who announced right before a national election that a presidential candidate is under investigation even before anybody reviewed the potential evidence. (Whether James Comey was taking advantage of the times or succumbing to them, only he knows.) It shouldn’t need to be said that bright-size performative behavior undermines the duller virtues of public servants who must abide process, especially when the crowd’s at full throat.

On Monday night we four went trick-or-treating and, uneasily by now, I figured I’d see the stunt through, so I put the Trump wig and the “BIGLY” card back on. This time I also carried a notebook. Usually political caricature is an acceptable lampooning of authority, but while dressing up as Trump isn’t the same as “being” Hitler or a Klansman, for a lot of people he’s on the continuum, somewhere beyond Nixon and over the line.

“Why are you Donald Trump?” a four-year old ninja wanted to know. “He says bad things.” Up and down the city sidewalks superheroes and witches berated me: “It’s HIM!” and “Boo Mr. Bigly!” and “Sad man!” and “Let me see your hands!” and “You’re the puppet!” and “Shame on you!” and “He’s saying big league!” This is, after all, a college town. It’s also an international town and, at a street corner, a man with a Russian accent looked me over as he said, “We’re from the Wiki dark side. He kills his mother in the end.” I was still mulling that one when I noticed a group of teenaged skeletons close behind who were discussing what kind of harm they were going to do me.

In the face of derision, I was annoyed with The Chicken walking at my side for leaving me in the barnyard like this. I worked up faux-Trump inner-monologues. On a crowded portion of sidewalk: “Get out of my way, you disgusting slobs!” Passing a crying child: “Kid’s gonna grow up to be a weak loser.” And when there was the obvious expectation that I’d offer some in-character “wrongs” and “sads,” I obliged. I was exchanging this sort of banter with a group of African-American trick-or-treaters who were gleefully shaming me back, when I told them, “You’re the puppets!” There on the dimly lit sidewalk, it seemed to me that startled looks crossed their faces, and I saw myself for what I was: a white guy in a suit insulting black people.

Putting on costumes and disguises can offer surprising insight into our personal realities. During this long, unsettling election year, far more than at any other time in my life, I’ve thought of myself as a white guy, rather than just a guy. The juxtaposition of Trump playing to white male grievance just as the country is approaching a day when minorities will no longer be minorities is part of this. It’s a wincing reminder of what a great privilege it is to go through life thinking of yourself as just a guy, without any additional descriptor. And it’s chilling, even on Halloween, to be somebody other people can’t stand simply because of what you look like. I came home that evening miserable, and I’d brought it all upon myself. But I got to toss the wig when I didn’t want to play Trump anymore. Most people can’t so easily shed what makes them targets.