In

Invisible Man, Ralph Ellison’s

protagonist asks: “Could politics ever be an expression of love?” Our current

climate of division, fear, anger, recrimination, and even resignation clearly points

to an answer in the negative. However, the writings and ideas of Ellison, and

his close friend of fifty years, Albert Murray, should caution citizens of the

United States to keep in view how and why we’ve come so far, and to hold on to

the vision of possibility within our democratic principles.

As members of the Greatest Generation, Murray and Ellison lived through the Great Depression under Jim Crow, the global threat of fascism during World War II, and the revolutionary 1960s, when Martin Luther King Jr.’s ethic of Christian love and tactic of non-violent resistance moved the nation closer to a democratic ideal. The Civil Rights Movement itself is proof that politics can be an expression of love as well as struggle. Where do we go from here: chaos or community?

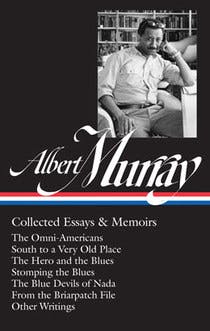

The writing of Ellison and Murray both contain the vision and value to not only cope with our current predicament, but to confront the blue devils of chaos and entropy with skill, resistance, and resilience, as witnessed in the Library of America’s Albert Murray: Collected Essays and Memoirs, a definitive collection of Murray’s nonfiction from 1964 to 2004, edited by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Paul Devlin. Murray transformed what Stanley Crouch aptly called the “decoy of race” into cultural idiom via a three-step process; his blues and jazz paradigm of humanity faced the harsh reality of life heroically, embracing inclusion and celebrating difference, affirming life itself along the way.

Albert Murray, born in Alabama on May 12, 1916, was a special, even quintessential American writer for the twentieth century: Local and global, black and Western, he was a modernist who respected the myths and rituals of early humans as much as he loved the stream-of-consciousness technique of James Joyce and William Faulkner. Murray didn’t confine himself to ideological boundaries—it’s little use boxing him into liberal or conservative camps, into one academic field or another. As a pragmatic American pluralist of the blues, his vision extended to the implications of quantum physics and Einstein’s four dimensions. Murray, like Ellison, championed the humanities, especially literature and music, over the structural determinist regime of sociology, which he felt stratified people into rigid ethnic and racial categories.

The political and the aesthetic intersect in Murray’s worldview, though he scrupulously avoided partisan political propaganda and the “politics of unexamined slogans.” Murray staunchly supported the Civil Rights Movement as the culmination of a century-long post-emancipation battle for black rights beyond the chains of ethnicity or race. He valued activism and protest as tactical measures, but doubted the long-term political value of what he called “the politics of moral outcry” to induce guilt and fear in whites.

The current backlash against identity politics presents an opportunity for progressives and post-modernists to reboot their strategy and rhetoric. “Producing guilt may or may not be fine,” Murray suggests in the introduction of his first collection of essays, The Omni-Americans (1970), “but stimulating intelligent action is better. And intelligent action always needs to have its way paved by a practical estimate of the situation.”

Murray was also a theorist of “elastic” human individuality: He renounced biological race and the racial worldview and instead emphasized culture as a more viable basis for understanding and interaction. American identity combines roots from Europe, Africa, and, of course, Native Americans, all mixed together with modifications according to region, economics, social power, cultural influence. The last people on earth who should adhere to ideas of biological, ethnic, or racial purity are Americans. (The increasing use of DNA tests—popularized in part by Gates’ PBS series Finding Your Roots and powerful short videos available on YouTube—demonstrates just how mixed, and mixed up, we really are.) “We can no longer afford to traffic in simple-minded and culturally inaccurate terms like ‘black’ and ‘white’ if they are meant to tell us anything more than loose descriptions of skin tone,” wrote Stanley Crouch in 1994 in the closing essay of The All-American Skin Game, or, The Decoy of Race. “We are the results of every human possibility that has touched us, no matter its point of origin.”

Murray’s blues idiom worldview, which he described as a secular form of existential improvisation, is summed up by his phrase “elegant resilience,” a synonym for “swinging” in jazz and “flow” in hip hop. “A definitive characteristic of the descendants of American slaves is an orientation to elegance,” he writes in From the Briarpatch File,

…the disposition (in the face of all of the misery and uncertainty in the universe) to refine all of human action in a direction of dance-beat elegance. I submit that there is nothing that anybody in the world has ever done that is more civilized or sophisticated than to dance elegantly, which is to state with your total physical being an affirmative attitude toward the sheer fact of existence.

Philosophers Kwame Anthony Appiah and Danielle Allen have described a worldview they call “rooted cosmopolitanism,” which I think describes Murray and the blues idiom to a tee. Rooted cosmopolitanism counters the insular nationalism exemplified by the conservative Prime Minister Theresa May, who recently said: “If you believe you’re a citizen of the world, you’re a citizen of nowhere.” Murray, unequivocal about his local Southern roots and nationality as a black American, believed that Americans are heir to the best of culture from all times and places—a global, cosmopolitan conception. Likewise, the blues is a vernacular music rooted in the black South of the United States that’s connected to Western church music harmonically as well as to music globally. The blues idiom is America at her best because it synthesizes “everything in the world as a matter of course, and feed[s] it back to the world at large as a matter of course.”

In Murray’s first published work of non-fiction, “‘The Problem’ is Not Just Black and White,” which appeared in Life magazine in 1964, was a swashbuckling dissection of seven books on the Civil Rights Movement. Murray had retired as an Air Force major two years before and he was game to wade in heated waters of public discourse, so his friend Ellison, by this time an icon of American letters, hooked him up for his debut.

Murray came out the gate slicing and dicing white liberals and black radicals alike, as well as giving affirmative nods where they were due. Injustice has many levels and Murray focused on the ideas and images that undergird it: Redneck racists, grounded in regional and racial tribalism, were all-too-obvious for Murray; it was the liberal condescension underpinning an attitude of white superiority that was more stealthy and treacherous.

Nowhere do the smug assumptions which underlie the ideas of white supremacy work more insidiously than among the so-called American liberals, the self-styled “friends of the Negro.” Their methods are rooted in the jargon of social science, their judgments based on tricky statistics, their proposed solutions basically materialistic—and seldom if ever do they stop to consider Negroes as people. Instead, these authors’ good intentions become so enmeshed in misinformation and guesswork that their books wind up preaching the same false generalities as white supremacists. The only difference is that their attitude is condescending rather than malevolent.

In the review, Murray isn’t afraid to name names: jazz critic Nat Hentoff, Charles Silberman, author of 1964’s Crisis in Black and White, and immigration historian Oscar Handlin, among others, get the boot. Murray shakes his head at the Washington bureau chief of JET, Simeon Booker, for his report on the so-called new black militancy: “Booker, like most other reporters, Baldwinizes too much about the Negro’s new liberation from fear of the white man,” he writes. “But he has his facts backward: What the Negro has always been concerned about is the white man’s sometime hysterical fear of him, a fear that expresses itself all too often in terms of lynch mobs, police brutality, racist juries, unconstitutional state laws, and fanatical defiance of federal authority.”

In The Omni-Americans, Murray demonstrated how and why black American culture is central to the American mainstream, despite social, economic, and political obstacles. Twenty four years later, Murray would thrash Andrew Hacker’s thesis in the New York Times bestseller Two Nations: Black and White, Separate, Hostile, Unequal (1992) by listing major U.S. cities with black mayoral leadership, and referencing the multi-million dollar salaries of black athletes accepted by fans of all backgrounds in various sports, as counter-examples. “Two nations? Only two?” Murrays asks with incredulity. “What about the Asians, Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and other not very white U.S. citizens from Latin America and elsewhere? One thing that does not seem to have changed very much during the last twenty five years is the pessimism of white academic experts on black prospects.”

The Library of America volumes also include Murray’s unpublished work, such as his fascinating 1966 essay on Black-Jewish relations titled “U.S. Negroes and U.S. Jews: No Cause for Alarm”—which, as Gates and Devlin explain, was commissioned and then rejected by the New York Times Magazine. The editors instead published James Baldwin’s “Negroes are Anti-Semitic Because They’re Anti-White” a year later, presumably because of Baldwin’s greater fame and visibility, and the likelihood his incendiary title would draw more attention.

The Times editors could condescend to Baldwin’s repetitions of “hatred” throughout his essay to feel sorry for the poor, poor Negroes. Murray, who didn’t tolerate condescension, took a more measured approach than Baldwin, stating without reservation that blacks on the whole are not anti-Semitic, that Jewish philanthropy and support of civil rights for all is greatly appreciated, but that some blacks resent some Jews for certain social and economic atrocities. I suspect that what may have ultimately closed the door to publication was Murray’s audacious, stinging stand regarding particular Jewish intellectuals who were, he claimed, “persisting in misrepresenting and misinterpreting the rituals and motives of U.S. Negro life in terms of clichés and values peculiar to the Jewish tradition, [and] have been propagating and ‘documenting’ a new theory of Negro inferiority.”

By the publication of The Omni-Americans, a collection of pieces he had published in The New Leader and several other periodicals, Murray was primed to influence the national discourse on race, culture, and American identity in the post-Civil Rights era. After all,” argued Murray in the introduction, “someone must at least begin to try to do justice to what U.S. Negroes like about being black and to what they like about being Americans.”

Henry Louis Gates’s 1996 New Yorker profile, “King of Cats,” recalled Murray in the ‘70s as a “lithe and dapper man with an astonishing gift of verbal fluency, by turns grandiloquent and earthy.” Walker Percy, one of the notables Murray spoke with for his 1971 memoir, South to a Very Old Place, thought The Omni-Americans “well may be the most important book on black-white relations in the United States, indeed on American culture, published in this generation.”

A key Murray insight is that the different perceptions of white and black Americans results not only from the social effect of race, but also from distinctive ethnic and cultural idioms. Nevertheless, he writes in one of the most quoted passages from The Omni-Americans:

American culture, even in its most rigidly segregated precincts, is patently and irrevocably composite. It is, regardless of all the hysterical protestations of those who would have it otherwise, incontestably mulatto. Indeed, for all their traditional antagonisms and obvious differences, the so-called black and so-called white people of the United States resemble nobody else in the world as they resemble each other. [Emphasis in original]

Americans of any stripe share in the promises found in the nation’s founding documents, as well as our motto, E pluribus unum: out of many, one. The promises of our social contract clearly remain unfulfilled, but to Murray they remained ancestral imperatives, lodestars for fugitive slaves fleeing for freedom via the Underground Railroad. His image of E pluribus unum was “that of a mainstream fed by an infinite diversity of tributaries.” The hue of that mainstream is “the color of infinity.”

Murray’s method in The Omni-Americans was akin to a research detective’s, which in The Hero and the Blues he described as: “finding clues bearing on the nature and cause of specific troubles.” His concern was less “political injustice as such” as the “inaccuracies and misconceptions that contribute to and even rationalize injustice.” Positivist social science, which employed the tools of clinical psychology to pathologize the image of black citizens, reinforcing stereotypes and racial bias, was his main culprit. Under the guise of objectivity, he argued, the social sciences abstracted and obscured the lived reality of black folk. The insidious result was the media, policy-makers, and even black spokesmen taking “social science fiction” as real, spreading confusion and harm.

Stanley Elkins’s Sambo model, the Moynihan Report, Kenneth Clark’s renderings of black degradation, and William Styron’s projection of emasculation, sexual repression, and servility onto his fictional portrayal of Nat Turner were each subjected to withering critique in The Omni-Americans—Murray’s most polemical book. He also deemed the protest fiction of James Baldwin and Richard Wright inadequate, not only as representations of the fullness of black American life in Harlem and the South, but because he found their “frames of rejection” too beholden to moral outcry to leave enough space for individual agency and the novelist’s ambivalence about the human condition.

Murray employed “Some Alternatives to the Folklore of White Supremacy” as the sub-title of The Omni-Americans. He considered race a “sterile category,” “hardly useful as an index to human motives as is culture.” Here are Murray’s aforementioned three steps—deconstruction, re-framing, and reconstruction—crucial to liberation from the shackles of racial thinking.

Murray first deconstructed white supremacy by unmasking it as “sociopolitical and psychopolitical folklore.” He did the same for the corollary of white superiority found in discourses of black “cultural deprivation,” “self-hatred,” and so-called “culture of poverty” by coining the phrase “the fakelore of black pathology” as a tactic of homegrown deconstruction. Second, he re-framed race as idiom: A characteristic mode of expression of a people. During Murray’s youth to middle age, “Negro” was the accepted term for native-born U.S. black folk. The “Negro idiom” was a “style and way of life” lived by African-derived Americans. Murray extended the “Negro idiom” from an ethnic domain to an expansive aesthetic with the blues and jazz as primary metaphors.

Third and finally, Murray confronted race by re-constructing American identity as omni-American, a hybrid mixture, a synthesis and composite brought together by the values and principles of the nation’s “sacred” founding documents: the Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, and the Bill of Rights. Omni-Americans are the many comprising the oneness of American identity. That oneness is an idea, an ideal, a democratic horizon of aspiration, yes, but without such a vision, the people and the very nation may perish.

To Albert Murray—who experienced the full breadth of the twentieth century, passing away in 2013 at 97—human life was much more than the political survival of the fittest. If, however, there were an existential threat to the Republic and to humanity, as was the case during World War II, Murray’s response would have been to fight those authoritarian dragons of chaos with the best tools at one’s disposal—perhaps even employing an update of what Murray called Reverend Dr. King’s “political jiujitsu,” using the opposition’s own strength against them.

If politics is the art of the possible, then to Murray, art forms such as the blues and jazz, enactments of American civic ideals in sound, are resilient frames of acceptance and pathways of possibility. Murray’s matter of ultimate concern, divined from the thousand or so pages of this Library of America edition, was art and improvisation for life and humanity’s sake. In the midst of the pain, chaos, confusion, hysteria, conflicts and uncertainty of the moment, and apprehension about the future of our nation, the ability to express joy is paramount: to sing, swing, stomp the blues, dance our thoughts, feelings, and actions, and to freestyle on the breaks, dissonance, and asymmetry of our lives for as many measures as we’ve got, because the black and the blues will most certainly be back tomorrow.